Discovering and understanding – translators have always been explorers. Interview with Lise Chapuis

Author: Federica Malinverno (ActuaLitté)

Lise Chapuis has a PhD in French and Comparative Literature. One day she fell in love with Italian, so much so that she became a translator. She is also in charge of the “Selva selvaggia” series of publishers L’Arbre vengeur, which gives French readers the chance to discover numerous works of Italian literature, both classic and contemporary.

What made you decide to become a translator and why from Italian?

I have no Italian roots and I didn’t learn Italian at school, just English and German, and a lot of Latin. I started coming to Italy when I was studying modern literature – the usual things, visiting Italy’s famous art cities, museums, Venice, Florence… It was an authentic revelation. That is when I decided to start learning Italian, because I wanted to, before studying the language at university. I always liked languages and Italian was the language that enabled me to pursue that interest. I have to say that, even today, after years of study and work, I still discover just how rich this language is every day.

How long have you been working as a translator?

My first translations date back to 1986-87. I was a French language assistant at the University of Pavia when a friend of mine who taught Italian literature, Maria Antonietta Grignani, told me I just had to read a lovely little book published by Sellerio: Donna di Porto Pim, written by a certain Antonio Tabucchi. When I read the book, I thought that I would have loved to have written something similar. And how could I share this discovery? That was when the idea of translating came to me. In my enthusiasm, I immediately contacted Antonio Tabucchi, who was then teaching at the University of Genoa, and then got in touch with the publisher Christian Bourgois, who held the translation rights for the book in France. Bourgois offered me a contract not just for this book, but also for Notturno indiano, another of Tabucchi’s books I had very much enjoyed. That was the beginning of my career as a translator. I shall always be grateful to Antonio Tabucchi and Christian Bourgois for having put their trust in me. I don’t know whether it would be possible nowadays. Who knows, but I hope it would. They gave a beginner, someone they didn’t know, a chance. And they were well rewarded as the French translation Nocturne indien won the Médicis Etranger prize in 1987.

What changes have you noticed in the translation profession during your career?

Early on in my career I had the fortune to meet a translator, Claire Cayron, who was a member of ATLF (Association des traducteurs littéraires de France). Thanks to her, I quickly learnt that there was such a profession as translation, but that it was considered a subordinate profession and, therefore, had to be strengthened and defended. And I think that, thanks to the work carried out by translation associations, there have been some very positive developments. The status of translators has definitely improved.

We are currently witnessing an ever greater professionalisation of this activity and I think it is very positive that there are now a variety of specific courses at university level. I also think that a serious reflection has been begun regarding the specificity of the languages translated, in terms of training and publishing policies. There is still a massive imbalance between the languages translated, with enormous parts of the world in which very little is being translated, and this is unacceptable. Translators need to be able to discover and then understand. They have always had this role of explorers, of passeurs culturels. Fortunately, the visibility of translators has improved massively compared to when I started – some publishing houses now even put the name of the translator on the book cover.

During your career, what developments and trends have you noticed in Italian literature? And with regard to what is bought in France?

I don’t think that it is easy to have a complete idea of the literature of the period in which you live, either French or Italian. When I began, people spoke of Antonio Tabucchi, Pier Vittorio Tondelli, Andrea De Carlo, Daniele Del Giudice and Alessandro Baricco as a sort of “generation”. It seems to me that they shared a relatively classic language, which they may have acquired reading authors like Italo Calvino and Cesare Pavese, and that they dealt with themes that were not exclusively Italian (Tondelli and De Carlo were always travelling, Tabucchi spoke about Portugal…), as if transported by some sort of centrifugal movement.

Then it seems to me that there is a renewed interest in Italy’s diversity, a sort of inventory of local places and situations, with a more marked focus on regional themes and regional languages, or through the direct use of dialects or their evocation to provide a sort of backdrop. In both cases, it is something very challenging for translators… This trend is not a form of withdrawal, but a different way of looking at the surrounding world, of looking at what is universal through local identities. When Giosuè Calaciura, for example, speaks about the Borgo Vecchio, he is not speaking merely about the old part of Palermo, as he has often said, but of all the old parts of towns and cities all over the world.

It is true that one of the features of Italian culture and history is its strong regional basis, with a diversity of places of cultural production, especially publishing houses, which are better distributed in Italy than in France, even though there is now a tendency for publishing houses to be located in the north of the country. These strong regional ties, without some form of control, can, however, present the danger of a sort of provincialisation. As a result, some French publishing houses may yield to the temptation of focusing on issues that are almost stereotypes, above all when dealing with the south of Italy. I think this rather conventional sort of exoticism is dangerous in terms of understanding what is truly going on in Italy today.

Nevertheless, Italian literary creation is very dynamic and undoubtedly diversified as regards its settings, which is a specific feature of Italian literature and enriches it greatly. It is also dynamic in its approach to contemporary issues and in its search for formal and artistic elements.

As a translator, however, it seems to me that it is now more difficult to propose works to publishing houses, or at least to get them to accept truly original voices or original formal approaches. Is this due to the increased presence of literary agencies? I don’t know, but we need to be careful and hope that authors who do diverge from the beaten track can still be read by French readers. Often, this is only possible thanks to the work being done by smaller publishing houses such as L’Arbre vengeur, with which I work and which has agreed to publish authors like J.R. Wilcock, an original figure, or Francesco Permunian, a writer much closer to Guido Ceronetti than to the stereotypes of southern Italy. These publishing houses are undoubtedly taking a great risk and let’s hope that they continue to do so…

What is your opinion of the book market in Italy and the way it is developing?

I think that there is a great deal of creativity in Italy, that there is a very dynamic publishing industry, an industry that is very curious about what is happening abroad and very open to translation, even though translators have less visibility in Italy than in France. And the Italian publishing sector also receives far less support from the State. The literary world is very dynamic, however, with numerous websites, blogs, events, book festivals…

What books have you translated recently and what are you working on at the moment?

I have started translating Giosuè Calaciura’s latest book, Io sono Gesù, which met with critical acclaim in Italy when it was published by Sellerio earlier this year. I have been following the author for a long time now and this will be the sixth book of his that I have translated. The book’s topic (the life of Jesus before he became Jesus) is something that cannot fail to arouse your curiosity. I have always been struck by Calaciura’s narrative style, by his language, which blends the prosaic with the poetic, with surprising results.

A book I really enjoyed translating was Claudia Durastanti’s L’étrangère (La straniera, La Nave di Teseo, 2019), which will be published shortly by Buchet-Chastel. It is a sort of autobiographical novel about the experiences of a girl living between Italy and the United States whose parents are deaf. It has an original structure, with a sociological approach, and the language is characterised by bilingualism and the linguistic problems within the family. It was a very interesting book to read and, of course, translate. Viviane Hamy recently published, to coincide with the Roland Garros tennis tournament, Gianni Clerici’s La Divine, a biography of Suzanne Lenglen, an incredible woman, a tennis star of the 1920s, an authentic star. I had never translated a work of this kind, more historical than literary, and I found it fascinating to immerse myself in the reconstruction of an entire period. My last translation was just published by Denoël: Écrire, mode d’emploi à l’usage des auteurs en herbe et autres amoureux de la littérature by Vanni Santoni, a short, lively and slightly controversial text about the teaching of creative writing. Finally, I am also translating, together with a colleague, Laura Mancini’s novel Rien pour elle (Niente per lei) for the publishing house Agullo. This book explores, through the different stages of the character’s life, parts of Rome little-known to literature and even less so to tourists.

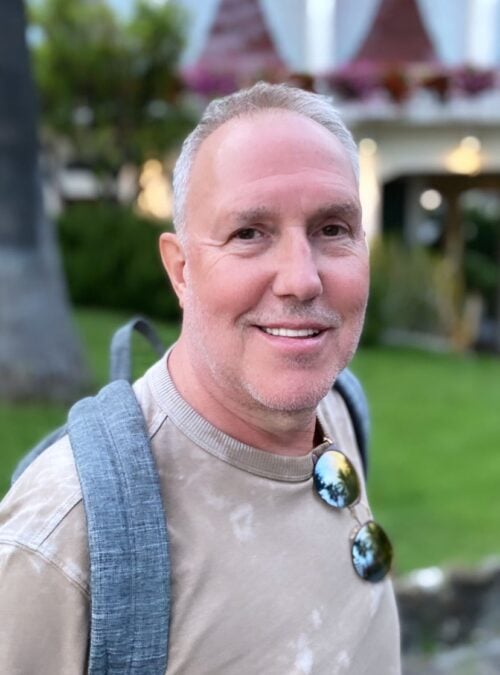

Photographic credits: Nan Palmero, CC BY 2.0; Lise Chapuis © Philippe Taris