Roberto Calasso in other languages

Author: Stephen Ferriter Smith

Stephen Ferriter Smith graduated from the University of Bologna and the University of Strasbourg in 2024 with a double master’s in European Literature. He currently works as a translator from Italian, German, and French into English.

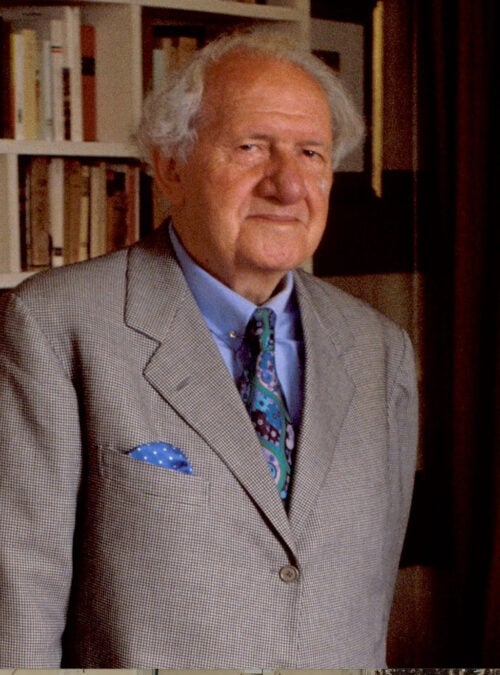

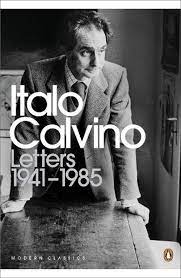

The literary life of Roberto Calasso (1941–2021) was particularly tied to the act of translation. Alongside commissioning, editing, and publishing literature in translation from all corners of world for sixty years, he worked as a translator during in the early years of the Adelphi publishing house, producing Italian editions of Ignatius of Loyola’s Il racconto del Pellegrino (1966), Friedrich Nietzsche’s Ecce Homo (1969), and Karl Kraus’s Detti e contraddetti (1972). Calasso’s own works are noted for being citation-filled and allusion-heavy, something that makes them often difficult to translate; reflecting on his translation of K. (2005), Geoffrey Brock describes the rigorous process of ‘triangulation’ was necessary to strike a balance between the author’s voice and the many lines of Kafka weaved around it. Despite this, the international success of books such as La rovina di Kasch (1983), Le nozze di Cadmo e Armonia (1988), Ka (1996), and Ardore (2015) seem to confirm Calasso’s assertion that “myth is that which is not lost in translation.” In turn, his works have been translated into at least 26 languages.

The first translation of a text penned by Calasso appeared not in a neighbouring European country, but in Buenos Aires in 1962, when a Spanish translation of his essay Th. W. Adorno, il surrealism e il “mana” (Paragone n. 138, 1961) was published in Victoria Ocampo’s literary journal Sur. A certain symbiosis would be seen between Calasso and Latin American intellectuals throughout his early career, as seen in a letter written by Juan Rodolfo Wilcock to Adolfo Bioy Casares in February 1966: “I am trying to have Plan de evasión published by a press more intelligent than Bompiani, who are certainly dignified, but poor. If you have a copy left, please send it to Roberto Calasso – 93 via Ippocrate – Rome. This young man, who wrote an immense thesis on Thomas Browne, has not been able to read Borges’ essay about him, not even in the British Museum.”

The thesis mentioned here, I geroglifici di Sir Thomas Browne, would be published in Central and South America in collaboration with the Fondo de Cultura Económico (Los jeroglificos de Sir Thomas Browne, tr. Valerio Negri Previo, 2010). Its publisher Sexto Piso was founded in Mexico in 2002 by Luis Alberto Ayala Blanco, who modelled his editorial approach after Calasso’s – a fact that has led to them being dubbed the “Mexican Adelphi”.

The importance of translation for Calasso’s works is no clearer than in the case of his first book and only novel L’impuro folle (1974), itself inspired by the first Italian translation of the memoirs of famous Freud case study Daniel Paul Schreber (Memorie di un malato di nervi, tr. Federico Scardanelli & Sabina de Waal, 1974). The two books proved thematically inseparable to the point that Calasso’s novel was errantly listed as the Italian translation of Schreber’s book in the 1976 Index translationum. Though not met in Italy with the acclaim that his subsequent works would garner, this debut work attracted enough attention to be translated in France (Le fou impur, tr. Danièle Salenave, 1976), Argentina (El loco impuro, tr. Italo Manzi, 1977), and Germany (Die Geheime Geschichte des Staatspräsidenten Daniel Paul Schreber, tr. Reimar Klein, 1980). The novel has been revisited over time, with Sexto Piso producing a new Spanish translation (tr. Teresa Ramírez Vadillo, 2003), Gallimard releasing a revised French translation (tr. Danièle Salenave & Éliane Deschamps-Pria, 2006), and Suhrkamp republishing the German edition under a decidedly snappier title: Der unreine Tor (2017).

In 1983, the publication of La rovina di Kasch marked the first chapter of what would become an eleven-volume work informally entitled the Opera in corso (“Work in Progress”). With Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord acting as the book’s “master of ceremonies”, a French translation seemed inevitable and appeared four years after its release (La Ruine de Kasch, tr. Jean-Paul Manganaro & Jean-Baptiste Michel, 1987). France would be an anchor throughout Calasso’s authorial career, thanks in part to his friendship with Antoine Gallimard. The Florentine author would also sporadically become a media presence there, appearing in a televised discussion with René Girard (La crise, de la violence au sacrifice, FR3, 1990) and being hosted three times on France Culture radio programmes (2011, 2012, 2013). Calasso was posthumously awarded the inaugural ‘3466’ prize by the journal Le Grand Continent for his contributions to European humanism.

Translations of La rovina di Kasch into languages other than French would not appear until after Calasso had become an international bestseller with Le nozze di Cadmo e Armonia (1988). A runner-up for the Premio Strega, the book would win the Prix européen de l’essai Charles Veillon in 1991. Thus, in the early Nineties, the somewhat predictable French (tr. Jean-Paul Manganaro, 1991), German (tr. Moshe Kahn, 1991), and Spanish (tr. Joaquim Jordà, 1994) editions of the work found themselves among a parade of translations in various European languages: Catalan (tr. Juan Castellanos & Eulalia Roca, 1990), Portuguese (tr. Maria Jorge Vilar de Figueiredo, 1990; tr. Nilson Moulin Louzada, 1990), Danish (tr. Nina Gross, 1990), Dutch (tr. Elly van der Pluym, 1991), English (tr. Tim Parks, 1993), Swedish (tr. Ingamaj Beck, 1994), and Polish (tr. Stanisław Kasprzysiak, 1995). Since its publication, the book has been translated into at least 19 languages, including Finnish (tr. Elina Soulahti, 2001), Estonian (tr. Mailis Põld, 2002), and most recently Romanian (tr. Petru Iamandi, 2022) and Traditional Chinese (與神共宴:古希臘諸神的秘密與謊言, tr. 金科羽, 2023). Calasso’s rise to international fame inspired many translators to recuperate the first part of his Work in Progress, and La rovina di Kasch was subsequently translated into English (tr. William Weaver & Stephen Sartarelli, 1994), German (tr. Joachim Schulte, 1997), Dutch (tr. Elly van der Pluym, 1994), and Spanish (tr. Joaquim Jordá, 2001). It would also be the first of Calasso’s books to appear in modern Greek (Η καταστροφή του Κας, tr. Μαρία Κασωτάκη, 1999), followed by Le nozze di Cadmo e Armonia (Οι γάμοι του Κάδμου και της Αρμονίας, tr. Γιώργος Κασαπίδης, 2005).

After the success of its second instalment, the majority of the Work in Progress would enjoy a similarly international readership; as of 2025, all eleven books are available in English, and ten have been translated into French, Spanish, German, and Dutch, with only La tavoletta dei destini (2020) yet to be translated. A considerable number of the books have also been published in Polish, Portuguese, Swedish, Catalan, and Danish. Volumes from Calasso’s Work have also enjoyed a considerable number of translations in Eastern Europe: Ka (1996) into Slovenian (tr. Vera Čertalić & Gašper Malej, 2005); K. (2002) into Czech (tr. Zdeněk Frýbort, 2008) and Serbian (2009); La folie Baudelaire (2008) into Croatian (Baudelaireova sjenica, tr. Mate Maras, 2017) and Russian (Сон Бодлера, tr. Александр Юсупов & Мария Аннинская, 2020); and L’innominabile attuale (2018) into Croatian (Neimenjiva sadašnjost, tr. Katarina Penđer, 2023). In Turkey, meanwhile, the first four books of the Opera are available (Kasch’ın yıkılışı, tr. Levent Cinemre, 2004; Kadmos ile Harmonia’nın Düğünü, tr. Levent Cinemre, 2005; Ka, tr. Eren Cendey, 2004; K., tr. Leyla Tonguç Basmacı, 2016).

When discussing the non-European countries that have shown a strong interest in Calasso’s Work in Progress, it is difficult not to mention India. In order to write Ka and Ardore – both of which deal with Vedic mythology – Calasso immersed himself in Indian culture. And this interest has seemingly been reciprocated with Hindi translations of La rovina di Kasch (tr. Brij Bhushan Paliwal, 2011), Ka (tr. Devendra Kumar, 2011), and Ardore (2017); Calasso was invited to the Jaipur Literature Festival to present the latter. Ka’s English translation (tr. Tim Parks, 1999) has also proved instrumental to the dissemination of Calasso’s work in India, serving not only as the basis for the Malayalam (tr. K. B. Prasannakumar, 2010) and Tamil (tr. Anandh Kalachuvadu, 2015) editions, but also for an adaption of the work into an illustrated children’s book (Geeta Dharmanarajan & Suddhasattwa Basu, The Story of Garuda, 2004). The Work in Progress was concluded with the posthumous publication of Opera senza nome (2024), which is yet to be translated into any language.

Beyond this main corpus, Calasso’s essayistic works have had a similarly international reception. His first essay collection I quarantanove gradini (1991) was first read in Spain (tr. Joaquim Jordà, 1994), arriving quickly in French (tr. Jean-Paul Manganaro, 1995) and Portuguese (tr. Maria Jorge Vilar de Figueiredo, 1998) translations, and later appearing in English (tr. John Shepley, 2001) and German (tr. Joachim Schulte, 2005). Originally a series of lectures given at Oxford University, 2001’s La letteratura e gli dèi represents his most widely translated critical work, translated immediately into English (tr. Tim Parks) and Polish (tr. Stanisław Kasprzysiak), and into French (tr. Jean-Paul Manganaro), Spanish (tr. Edgardo Dobry), and Dutch (tr. Els van der Pluym) the following year. The work has had a sustained reception over the years, being made available in Turkish (Edebiyat ve Tanrılar, tr. Ahmet Fethi, 2003), German (tr. Reimar Klein, 2003), Portuguese (tr. Jônatas Batista Neto, 2004), and, most recently, Russian (Литература и боги, tr. А. В. Ямпольская & С.Н. Зенкин, 2018).

La folie qui vient des Nymphes was also originally a lecture, given in French at the Collège de France in Paris in 1992 and published in Italian more than a decade later in an eponymous collection of essays (La follia che viene dalle Ninfe, 2005). The book was first translated into Spanish (La locura que viene de las Ninfas, tr. Teresa Ramírez Vadillo & Valerio Negri Previo, 2008) before reappearing in France twenty years after it was first read aloud (La folie qui vient des Nymphes, tr. Jean-Paul Manganaro, 2012). The essays on library organisation that make up Come ordinare una biblioteca (2020) would be published in Spain (Cómo ordenar una biblioteca, Edgardo Dobry, 2020) and in Brazil (Como organizar uma biblioteca, tr. Patricia Peterle, 2023). Both essay collections were published together in a single edition in Polish translation (Kręte ścieżki, tr. Joanna Ugniewska, 2023). Calasso’s more recent essay collections – Allucinazioni Americane (2021), Ciò che si trova solo in Baudelaire (2021), Sotto gli occhi dell’Agnello (2022), and L’animale della foresta (2023) – have so far evaded translation. Meanwhile, the autobiographical works Memè Scianca and Bobi have been translated into Spanish (Memè Scianca, tr. Edgardo Dobry, 2023), Catalan (Memè Scianca, tr. Pau Vidal, 2023), and Portuguese (Bobi, tr. Pedro Fonsecar, 2024), appearing together in the Polish volume Memè Scianca/Bobi (tr. Joanna Ugniewska, 2024).

Calasso’s success as a publisher is certainly one of his most universal allures, and this explains the international reception of L’impronta dell’editore (2013), which has been translated into ten languages – among which Estonian (Kirjastaja jälg, tr. Heli Saar, 2019, Russian (Искусство издателя, tr. Александр Дунаев, 2017) and Traditional Chinese (独一无二的作品,2018). It is also the only of his works to have been translated into Lithuanian (Leidėjo menas, tr. Goda Bubylenko, 2024). Cento lettere a uno sconosciuto (2003), meanwhile, received minor interest abroad, with editions in German (Hundert Briefe an einem unbekannten Leser, tr. Roland H. Wiegenstein, 2006) and Spanish (Cien cartas a un desconocido, tr. Edgardo Dobry, 2007). One of the most interesting examples of Calasso’s editorial impact on translated literature was his reedition of Franz Kafka’s ‘Zürau Aphorisms’ (Aforismi di Zürau, 2004), which became the basis for a new German edition (Die Zürauer Aphorismen, 2006) and all subsequent translations, including into Persian (پندهای سورائو کافکا, tr. Guita Garakani, 2015).