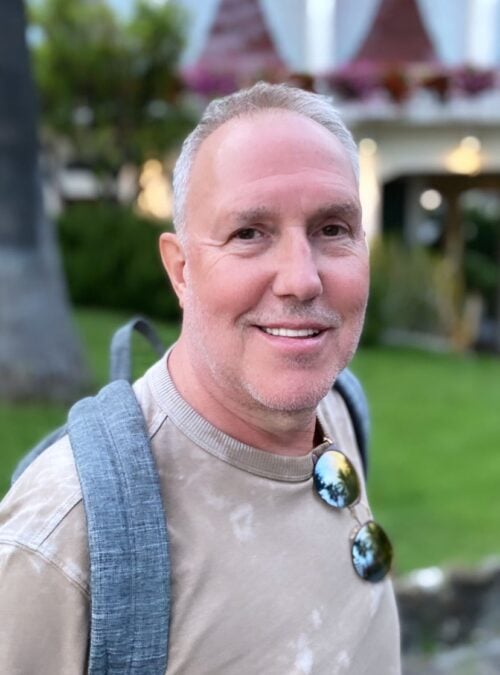

Interview with René de Ceccatty

Author: Paolo Grossi

Starting in April, together with the French website Actualitté, newitalianbooks will be publishing a series of interviews with people who, for various reasons, have an important role in mediating between the French and Italian publishing sectors (literary critics, essay writers, translators, publishers, booksellers, etc.).

Our guest today is René de Ceccatty. As well as translating numerous works by Italian authors (Pasolini, Leopardi, Saba, Moravia, etc.), René de Ceccatty is also a publisher, playwright and novelist. Over the last few years, he has been busy translating works by Dante: the Divina Commedia, complete and in octosyllabic verse, the Vita nova and the Convivio.

France is one of the countries in which Italian books are most translated and published. What is your overall view of the situation as regards the translation of Italian books in France?

It is true that many Italian books (narrative, poetry, essays and theatre) are translated into French and there are several reasons for this. The closeness of the two languages facilitates the task of the translator (compared to other languages, including Neo-Latin languages) and there is also an undoubted cultural affinity, a familiarity that renders Italian works, above all novels, particularly attractive to French readers. Paradoxically, however, Italian is not taught very much in France, so there are very few French readers who are able to read Italian works in the original. That is why there are so many translations.

French tourists visiting Italy, attracted by its artistic and cultural treasures and its diverse natural beauty, read before they go to enrich their stays (in Rome, Florence, Venice, Milan, Naples, Sicily or by its lakes). And the role that Italian cinema has had in helping French people to discover Italian literature should not be overlooked. I am not thinking solely of the great directors like Fellini, Visconti, Pasolini, Antonioni, Bertolucci, Scola and Mauro Bolognini, but also the actors. Claudia Cardinale was the star of countless films based on key novels of the twentieth century (Gli indifferenti, La Storia, Il bel Antonio, Il Gattopardo, Senilità, La ragazza di Bube) and it is thanks to her performances that many French readers have discovered Moravia, Elsa Morante, Brancati, Lampedusa, Svevo, Cassola…

One might say that the French publishing sector has been in step with this interest, often quickly publishing translations of the latest Italian works, with some important exceptions every now and then. Basically, however, French readers have not missed out on any of the major literary events or Italian writers, let’s say, from d’Annunzio onwards. Moravia, Pavese, Vittorini, Calvino, Elsa Morante, Lalla Romano, Gadda, Anna Maria Ortese, Pasolini, Bassani, Soldati, Francesca Sanvitale, Natalia Ginzburg, Rosetta Loy and many other top writers, including avant-garde authors from Gruppo 63, have been immediately translated, with varying results. Numerous narrative works have been published, also those of the newest authors (Elisabetta Rasy, Sandro Veronesi, Nicola Lagioia and, of course, Elena Ferrante, who is a publishing phenomenon on a par with Umberto Eco), and they are often as successful in France as they are in Italy. Taking a look at translations up till the beginning of the 1990s, we have to pay tribute to some very determined figures who strove to bring to the attention of French readers works with which they were intimately acquainted – Maurice Nadeau, Georges Piroué, François Wahl, Hector Bianciotti, Patrick Mauriès, Samuel Brussel, Mario Fusco, Jean-Noël Schifano, Dominique Fernandez, Michel Arnaud, Bernard Simeone and Jean-Paul Manganaro. There are many critics, publishers, translators and university lecturers and professors who also deserve to be mentioned, such as Jean-Michel Gardair, who was a professor, translator and writer. Poetry, on the other hand, poses specific problems. Quasimodo, Montale, Zanzotto, Pasolini, Mario Luzi, Giorgio Caproni, Attilio Bertolucci, Leonardo Sinisgalli and Patrizia Cavalli were all translated, on the whole, very quickly, but the difficulty in finding translators good enough to translate these poets, that is translators capable of rendering the idea of the original text, means that sometimes French readers have not been as captivated by the translated text. It must also be added that poetry is held in greater esteem in Italy than in France. As for the classics, poets like Dante, Petrarca, Boccaccio, Basile, Masuccio Salernitano, Tasso, Ariosto, Goldoni and Gozzi (who is now fashionable again) all immediately entered the European tradition, which includes France, and were immediately accepted by French culture, which they have greatly influenced. You then realise, however, that Vico, Leopardi and Manzoni, who are considered key figures in Italian culture, did not, until quite recently, start to enjoy the same success in translation in France. With the exception of his Canti, Leopardi’s other works were only translated fairly recently and his status as a philosopher was for long ignored. In France, Alessandro Manzoni has never been considered as great a novelist as Stendhal, Flaubert, George Sand or Balzac. There is considerable resistance in France to Manzoni, even though, culturally, he was part French and could have had his works translated immediately. Collodi has been luckier than Manzoni, but Walt Disney might have had something to do with that! As for more recent literature, even though some living (or recently deceased) writers have enjoyed cult status in France (such as Antonio Tabucchi and Erri De Luca, who, in a certain sense, have taken the place once occupied by Italo Calvino), today’s Italian literature does not enjoy the same status as that of thirty years ago. Its popularity has, therefore, waned a little. I would like, however, to highlight an exception: the rediscovery in France of the works of Goliarda Sapienza, whom the translator Nathalie Castagné successfully promoted, not just by translating her works, but also by presenting her at meetings in bookshops and in interviews, creating an authentic publishing sensation, which resulted in Italian publishers reconsidering her works. Goliarda Sapienza, all of whose works have been republished by Einaudi, has now found her place in the history of Italian literature, after being previously ignored. This was an instance of the boomerang effect and it is worth mentioning because it is so exceptional. As for Italian philosophy, it is very much alive in France and has been widely translated. The presence of an Italian lecturer (Carlo Ossola) at the Collège de France until last year shows just how highly Italian thinking is considered. Agamben and, more recently, Roberto Esposito have both been translated, together with many others, including Roberto Calasso and Claudio Magris. And the intellectual Maria Antonietta Macciocchi has had an indisputable influence on the political and philosophical dialogue between France and Italy.

Does Italian literature from the last century, the literature of the Novecento, have the place it deserves on the bookshelves of France’s bookshops?

Well, I think I have partly answered that question as regards Leopardi and Manzoni. But there are undoubtedly many other gaps. Among the poets, Carducci and Pascoli have been generally overlooked. Ippolito Nievo has been translated, but is considered more of a curiosity than a member of that small group of authors who can never be ignored. It is, of course, necessary to make a distinction between what is studied at university and what is present in bookshops or in the mainstream media. Teachers of Italian studies are completely in line with the scale of values used by their Italian counterparts and the editions of the Belles-Lettres or the Cahiers de l’Hôtel de Galliffet fill the gaps in these two centuries. But, here, I am talking about the presence of authors in bookshops and the culture of curious readers, not specialists. Similarly, many writers at the turn and beginning of the twentieth century, such as De Roberto, Verga and Borgese, are are still unacknowledged in France, even though they have been translated, thanks in particular to Jean-Baptiste Para, who has righted many injustices in his L’Arpenteur collection. One could then turn to the situation regarding Italian theatre, where Eduardo De Filippo continues to be performed, though less than Pirandello, while Raffaele Viviani is practically unheard of, despite the fact that Alfredo Arias staged a production of one of his plays in Naples before bringing his company to France.

In the last few years, you have published mainly translations of the great names in Italian literature, such as Dante and Petrarca. In this specific field, that of the “classics”, is there still much work to be done?

Translating the classics has certain specific features. As I already mentioned, these works were often immediately translated, with new revised translations being produced from one century to the next. But these translations are outdated, following criteria that change over time. Nowadays, there are two different approaches: the academic approach, which is the equivalent, one might say, of an excellent school version, destined to obtain the highest mark as the translator has perfectly understood all the lexical and syntactic nuances of the original, and has found equivalent expressions without any ambiguity, but not necessarily of great poetic inspiration, nor particularly elegant. “Inspiration” and “elegance” are subjective concepts, which are both questionable and change over time. And it is understandable that they are not always held in consideration in an “academic” evaluation of the excellence of a translation. Outside of the academic sphere, the criteria change. Translators must become mediators and enable ordinary readers, non-experts, to have a direct literary relationship with the text. In this case, translators have far greater freedom. And this is the freedom I gave myself when translating the Divina Commedia, in the knowledge that there were already numerous other translations based on different criteria, some of which are the exact opposite of the criteria I use. Then there are others that are closer to the need for readability (Jacqueline Risset), and others still in a more or less artificial verse, requiring certain acrobatics in terms of meaning and form, or in a fluid, albeit flat prose. Some use an archaising language bordering on abstruseness, while others are totally unintelligible without notes, etc. Each of these translations is based on a line of reasoning, which I respect even when I do not agree with it. In translating Pétrarca, but also Dante’s the Vita nuova, I was far more faithful to the original because I was able to follow the example of the French poets of the Pléiade, who had already provided a very French interpretation of the poetics of the dolce stil nuovo and Petrarchism. For the classics, there will always be a need for new translations as there is no such thing as the “definitive” translation or a translation that can be considered as the reference version. Take Boccaccio – although he has been translated numerous times, there is still no translator who has been able to fully render the vitality, inventiveness, profound learning and daring of the novellas in The Decameron. Boccaccio still awaits his Baudelaire…

Which Italian authors are you currently working on as a translator or essayist?

I will be translating Il pane perduto by Edith Bruck, who, although of Hungarian origin, writes in Italian as she has been living in Italy since the mid-1950s. She was deported to a concentration camp, where part of her family was murdered. When she was freed, she went to live first in Czechoslovakia and then in Israel before finally settling in Italy, where she married the poet and film director Nelo Risi. I only came across her fairly recently and quite by chance, thanks to an interview with Luce D’Eramo, which I read last year as Feltrinelli had asked me to write a foreword to his novel Ultima luna. I cannot explain how I had managed to miss the truly exceptional work of Edith Bruck. It was quite a revelation for me and I convinced Éditions du Sous-Sol (whose editor, Adrien Bosc, also works with the Éditions du Seuil, where I myself do editorial work) to publish her. I hadn’t felt that I was in the presence of a writer of such high calibre, in any case a writer who spoke to me directly, for quite some time. Three of her books had already been published in French by Kimé, after being recommended by the translator Patricia Amardeil and collection editor Philippe Mesnard, a Shoah specialist. Despite the quality of these books, no one noticed them. I will also be translating, to mark the 100th anniversary of his birth, an extraordinary interview Pasolini did with the Irish journalist, Oswald Stack, also known as Jon Halliday. I also have in mind an anthology of Sandro Penna, having already translated his prose (Un peu de fièvre) and several of his poems in magazines. I have just finished translating the poems of Moravia for Flammarion. I forced myself to concentrate my work as both translator and essayist on authors of paramount importance to me, whom I felt an urgent personal need to translate (such as Giuseppe Bonaviri), authors who, for one reason or another, I felt close to, in both literary and human terms, such as Pasolini, Moravia and Leopardi, to whom I have in any case dedicated books. Translating Umberto Saba (I translated many of his poems and practically all of his prose as I also retranslated his masterpiece Ernesto) was a fundamental experience for me. When I say fundamental, I mean that it also influenced my work as a writer, as I also write. It is precisely this dialogue that I am looking for. Taking advantage of the period of confinement caused by the pandemic, I concentrated on another language I have been translating from for a long time now: Japanese. For thirty years, I had been translating both classic and modern Japanese writers (following the same selection criteria that I had adopted for Italian) together with a Japanese friend, Ryōji Nakamura, who now teaches comparative literature at an important university in Tokyo. I decided to take the important step of translating Japanese novels on my own. I have just finished translating Botchan by Natsume Sōseki (I had translated six of his books with Ryōji) and right now I am finishing the translation of Kawabata’s Snow Country. These are activities I forced myself to do, not without a certain trepidation, as they are jobs “without a safety net”. But I felt the need to further my knowledge of this language. Despite my familiarity with Japanese culture, which I have been in contact with for almost as long as Italian culture, alone, I was unable to master Japanese as well as Italian, for reasons that are easy to understand. I believe that it is important to compare cultures – not just the culture you are born into and another culture, but various cultures all together. Furthermore, the void I felt from no longer translating from Japanese is what made me translate the Divina Commedia. It was inevitable that after translating Dante I would go back to Japanese. Kenzaburō Ōe, several of whose books I had previously translated with Ryōji Nakamura, also happens to love Dante, whom he frequently mentions. He even had a personal stamp made with tercets by Dante, which he uses to add a sort of dedication. As far as essays and biographies about Italian writers are concerned, I’m not sure yet. I am very happy about the success that my biography of Elsa Morante has had (thanks also to the translator Sandra Petrignani, who is quite rightly highly thought of in Italy) because I had feared that being French and not adopting a hagiographic tone would have been viewed negatively, but the reaction was, in fact, exactly the opposite! I am also happy that my biography of Sibilla Aleramo (speaking of authors who, in France, although they have been translated, do not get the recognition they deserve), which Mondadori had translated as soon as the book came out in France, has now been republished in Italy by a small publishing house that specialises in philosophical texts, inschibboleth. It is also going to have translated a book I wrote in 1994, L’accompagnement, which has no direct connection with Italy or Italian literature, even though everything I write is always, in one way or another, linked to my second homeland.