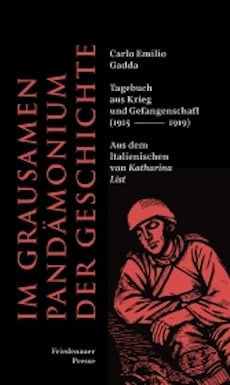

‘In the bloody pandemonium of history’: interview with Katharina List, translator of Carlo Emilio Gadda’s War and Prison Diary

Author: Katharina List, Catholic University of Eichstätt-Ingolstadt

Katharina List teaches Italian and French literature at the Catholic University of Eichstätt-Ingolstadt. She obtained her PhD with a thesis on Carlo Emilio Gadda and has published studies on 19th– and 20th-century Italy. Another area of her research is French Renaissance literature. She also works as a translator from Italian.

The first complete German translation of Carlo Emilio Gadda’s Giornale di guerra e di prigionia (War and Prison Diary) was published a few days ago in Germany by Friedenauer Presse. We discuss it with the translator.

How does this translation fit into the context of translations of Carlo Emilio Gadda’s works? In other words, what is the current “translation situation” for Gadda in the German-speaking world?

Gadda was translated into German relatively early on – the German version of Pasticciaccio was published as early as 1961 – and many of his works have been translated, at least in part. With the exception of his two major novels, Pasticciaccio and Cognizione, which are available in their entirety, only selections of his other narrative texts have been published, often in collections different from the originals. Furthermore, the latest translations date back mainly to the 1990s and are now almost all available only on the second-hand market. Nothing has yet arrived in Germany of what has happened since then in the world of Gadda’s editions – I am thinking in particular of the excellent new complete edition by Adelphi, whose volumes have been published for a decade now and often offer important innovations or additions to the texts. So there is still a lot to do!

Why has the Giornale di guerra e prigionia never been translated into German until now? Was it because of the difficulties of translation or rather because, within Gadda’s œuvre, it was considered, in some way, a minor, secondary work?

Part of the Diary dating back to Gadda’s imprisonment in the Celle camp had already been translated into German and published in 2014 by the Zu Klampen publishing house together with Bonaventura Tecchi’s memoirs of the two writers’ shared war imprisonment. Overall, however, it is certainly true that the book has remained in the shadow of Gadda’s narrative texts in the strict sense in Germany: the difficulties of translation, which do exist, are therefore not the main reason for the absence of a complete version. This is true, incidentally, for many other countries as well: the diary has so far only been translated into French, based on Einaudi’s censored and much shorter 1965 edition. While in Italy this text rightly occupies a central place in Gadda’s work, internationally it has yet to gain this recognition.

In tackling this translation, did you feel it was important to engage with the vast universe of literature bearing witness to the First World War?

During the preliminary research and subsequently during the translation, I immersed myself in this now almost boundless universe and read many diaries, letters and memoirs written after the First World War, both in German and Italian. Apart from the very different types of these texts, it was interesting to see how certain events (e.g. Caporetto, the great Italian defeat in which Gadda was taken prisoner by the Germans in October 1917) were perceived, described and evaluated differently by the two sides of the front. Of course, other accounts from the period were also useful and necessary reading for me, such as historical military almanacs and some very specific manuals, in order to understand and translate, for example, Gadda’s detailed description of the mechanism of his St. Étienne machine gun: in these passages, the hand of the future engineer is clearly recognisable.

What were the main difficulties you encountered in your work as translator of this book: the vocabulary? The syntax?

The vocabulary sometimes presents difficulties, especially with regard to weapons, military equipment and ranks, while the syntax is relatively simple by Gadda’s standards. Greater translation problems arise from the specific genre of the diary, a type of text which, by its very nature, may contain linguistic or grammatical inconsistencies. In Gadda’s diary, this happens surprisingly rarely, but where such inconsistencies do occur, I have not smoothed them out in the translation, but rather reported them, so that even in German translation there are occasional repetitions of words or syntactical imbalances.

What use did you find it necessary to make of footnotes?

I was very pleased that Andreas Rötzer of the Matthes & Seitz publishing house immediately accepted my proposal for an annotated edition. I believe that the notes are particularly useful for a German-speaking audience that is not familiar with Gadda’s life and Italian historical events in detail. The notes cover various areas: on the one hand, they provide an overview of Gadda’s personal and family background, his relatives, friends and the places he mentions in his diary. On the other hand, I have included historical and political information relating to events, battles or figures mentioned in the text, as well as some information about his imprisonment as a prisoner of war in Germany. Other comments concern issues and decisions relating to the translation, while others contextualise Gadda’s numerous literary references or quotations and establish links with his later works. Translating means engaging intensely with the text; one is forced to reflect at length on certain points, which in turn leads to comments that shed new light on some passages in the diary.

Why should a German-speaking audience, which may not yet be familiar with Gadda, read this book?

On the one hand, the diary is an extremely illuminating document as a direct testimony to a conflict of exceptional importance. This is particularly true for the German-speaking audience as Gadda naturally reports various reflections on an enemy who is hated but also admired. During his imprisonment in Rastatt and then in the Celle camp, Gadda not only deepened his knowledge of the German language, but in the final phase of the war he gradually acquired a very interesting internal and external view of Germany, for example on revolutionary processes, and of the Germans, who went from being captors to being defeated.

If you are not yet familiar with Gadda’s novels and short stories, or know little about them, the diary is an ideal introduction to his work: the notebooks not only vividly reveal the characteristic traits of the writer’s personality, his inclination towards acute analytical observation, his emotionality and his humour, but also contain many themes and motifs that would be developed in his later literary works. It can even be rightly said that his entire work was triggered by the trauma of the First World War. The pages of the Giornale demonstrate in an impressive way, almost in real time, how significant this experience was for him and to what extent.

N.B. The German translation of Carlo Emilio Gadda’s War and Prison Diary was published with the support of the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation and the SEPS (European Secretariat for Scientific Publications).