The memory of a passeur: Maurice Nadeau and Italian literature in France

Author: Marco De Cristofaro, University of Mons/University of Namur

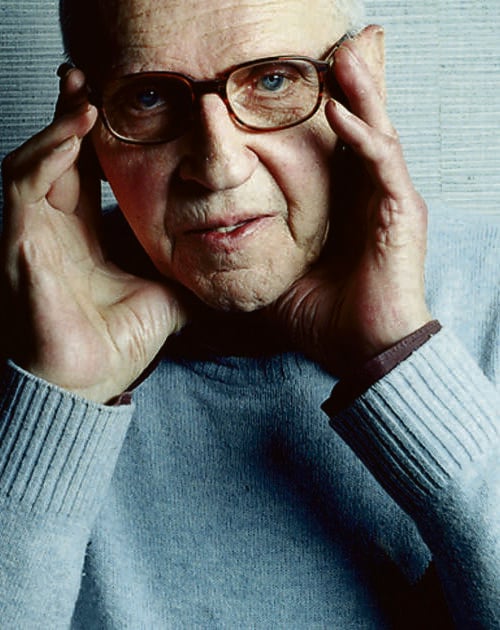

The attention that Maurice Nadeau (1911-2013) paid to Italian literature in his long and multifaceted career as a critic, writer, cultural promoter and publisher cannot be attributed to a passing interest, but rather it seems to have been a deliberate choice. In the three substantial volumes that collect a large part of his journalistic output, entitled Soixante ans de journalisme littéraire and published between 2018 and 2022 by Les Lettres Nouvelles-Maurice Nadeau (Nadeau 2018; Nadeau 2020; Nadeau 2022), we have identified over two hundred articles published in newspapers and magazines that the Parisian intellectual has devoted to Italian authors in the form of reviews or critical essays. These are accompanied by the books that the author of Histoire du surréalisme, in his role as an editorial passeur, had translated and introduced to French readers. Since its official debut on the book market, Italian literature has been a constant presence in the series founded and directed by Nadeau. While these were initially rather isolated choices, the literary production of the Peninsula soon became a recurring feature of his editorial selection.

The various studies that reconstruct his intellectual trajectory (1) agree with the idea that, after leaving Combat and founding a new magazine, Les Lettres Nouvelles, the Parisian intellectual embarked on a path “vers l’indépendance” (Samoyault 2020, p. 7). It was in this context that he moved, in 1954, to the court of an ambitious publisher: René Julliard. Julliard, in an attempt to oppose Gallimard’s cultural hegemony, based his strategy on three fundamental pillars: publish quickly, publish a lot and, above all, publish young authors (Simonin 1998). In such a landscape, Nadeau’s independence was assured: the financial resources of the new publishing house guaranteed him the freedom he needed to seek out young or little-known authors who, while not achieving high sales, did not place an excessive burden on the publisher’s finances, which, for its part, could boast a certain intellectual aura (Nadeau 2011). Thanks to this greater room for manoeuvre, Nadeau expanded the range of Italian authors available in France. In the newly created series “Les Lettres Nouvelles”, which significantly bears the same name as the magazine, Ugo Pirro’s Des filles pour l’armée was published in 1957 and, in particular, Renzo Rosso’s Un été lointain in 1963 and L’Écharde in 1965. Rosso’s case marked a new phase in Nadeau’s approach to publishing: the Parisian critic sensed the possibility of embarking on an authorial policy that, with some Italian writers, would become programmatic.

Nevertheless, in the early 1960s, internal economic reasons at Julliard forced Nadeau to look for a new space to continue his publishing activity, and so the “Les Lettres Nouvelles” series changed brands, moving to Denoël. It was undoubtedly a necessary choice, but one that was attentive to market dynamics and aimed at preserving decision-making and operational autonomy. The Denoël brand, in fact, despite being part of the Gallimard group, retained its independence, which would also be guaranteed to Nadeau. At Denoël, the Parisian critic built a solid and lasting relationship with an Italian author who would remain loyal to him for a long time: Leonardo Sciascia. The relationship between Nadeau and Sciascia was characterised by a series of contrasting events involving the personal and friendly bond between the two, the power relations within the French publishing world, the economic and commercial dynamics typical of publishing, especially in a transnational context, as well as the misunderstandings, antipathies, sympathies and obsessions that shape the book market. The relationship between Sciascia and Nadeau and its influence on the Sicilian author’s popularity with the French public was investigated by Mario Fusco (1996), who emphasised how Nadeau was a fundamental catalyst for interest in Sciascia in France, and by Giovanna Lombardo (2012), who carried out an initial survey of the exchange between the author of Il giorno della civetta (The Day of the Owl) and the Parisian intellectual through archive material consulted at the Fondazione Leonardo Sciascia. To further enrich the picture, I would like to refer to an article of mine (De Cristofaro 2023) in which I reconstruct, thanks to the consultation of unpublished archival material found at the Institut Mémoires de l’édition contemporaine (IMEC), the gaps left by previous studies, particularly in the late 1970s when Sciascia temporarily moved to the Grasset catalogue, only to return, in the name of a personal relationship and to the detriment of purely commercial interests, to his favourite publisher: Maurice Nadeau, who published a total of thirteen titles by the Sicilian author.

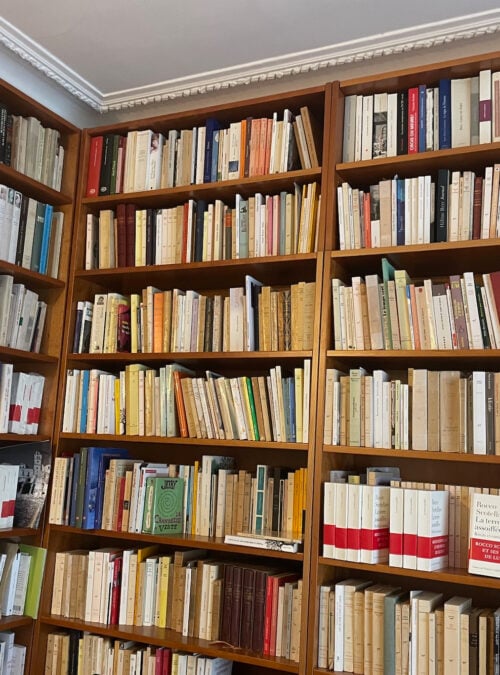

But Sciascia was not the only Italian writer to define Nadeau’s editorial identity. At the end of the 1970s, yet another commercial crisis in his series — which could no longer ensure stable sales — prompted him to leave Denoël. After a very brief collaboration with Robert Laffont, resulting in just one title to his credit — though an important one, Sciascia’s Candide — Nadeau made a definitive choice for his future, founding the publishing house that bears his name. The decision was not solely the result of a momentary need but was the outcome of a series of circumstances that defined a profound change in the book market in France. In 1981, after several years of negotiations between the various parties involved – politicians, distributors and publishers – the Lang law, named after the Minister of Culture in François Mitterand’s government, was passed, preventing discounts of more than 5% on the cover price of books. At the same time, the phenomenon of hyper-concentration, which began in the middle of the century (Schwuer 1998), seems to have caused two opposing movements: on the one hand, publishing groups became increasingly dominant in the market, while on the other, experienced managers undertook independent initiatives and, between 1974 and 1988, driven by these publishing veterans, around fifty new micro-publishing houses were established each year (Mollier 1995). Nadeau’s publishing house was fully part of this centrifugal movement, recognising translated works as a mainstay of its catalogue and, within this genre, reserving a prominent place for Italian authors. The ranks of the newly founded publishing house were filled by Pier Paolo Pasolini (La Nouvelle Jeunesse, 1979), Alessandro Manzoni (Les Fiancés, 1982; Histoire de la colonne infâme, 1982), Giorgio Caproni (Le mur de la terre, 1985; Le compte de Kevenhüller, 1987), Giuseppe Pontiggia (Le joueur invisible, 1985; Le Rayon d’ombre, 1988), five works by Sciascia, including reissues and new releases, and five titles by Andrea Zanzotto.

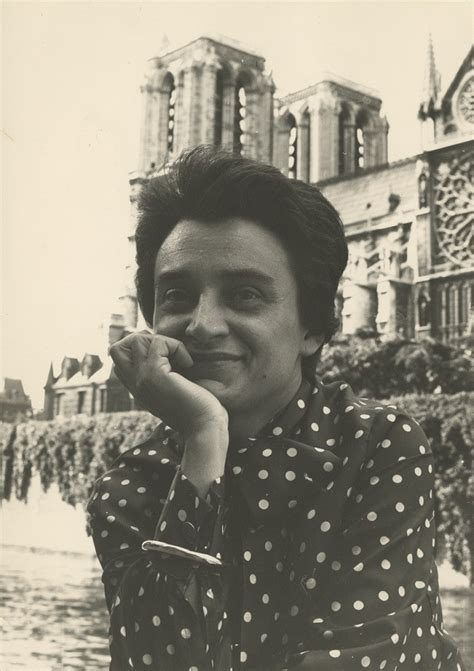

In addition to articles and books, Nadeau interacts with Italian culture in other ways, promoting its widespread dissemination in France. The Parisian critic is one of the protagonists of an ambitious initiative, launched in the 1960s, which aimed to create a transnational magazine with a tripartite French-Italian-German editorial team. The project, which was to be called Gulliver and whose boundless ambition was the cause of its failure, never saw the light of day, but it was the pretext for the creation of a network of relationships between the French publisher and some of the most prominent Italian intellectuals of the time, such as Elio Vittorini, Francesco Leonetti and Italo Calvino. Nadeau formed a strong friendship with Vittorini, writing the preface to the French translation of Diario in pubblico (Vittorini, Journal en public, 1961). Several years later, in 2006, Nadeau also published his Journal en public, thus paying tribute to his friend. This was not the only time that the Parisian intellectual took it upon himself to introduce an Italian author to the French public through a preface: in 1995, Nadeau introduced Silone’s Fontamara (Grasset, 1995), recalling the sensation caused by the text when it was first published in France in 1934.

The deep, almost innate bond between Nadeau and Italian literature is evidenced by his editorial memoirs, published in 1990 by Albin Michel (Nadeau 1990). Among the many French and European authors who represent turning points in Nadeau’s personal experience, there are two Italians: Ignazio Silone and Leonardo Sciascia. Both described as long-time friends, they are characters who are at once real and fictional and who perform a textual and symbolic function: reminding the reader of the complexity of the human, commercial, ideological, cultural and social relationships involved in literature and, more generally, in the book market.

But the centrality of this relationship is also confirmed from an external perspective. When Laure Adler asks Nadeau to explain the true meaning of being a publisher, he first draws on his memories of Italian writers:

You are surrounded by a constellation of very important authors, who now belong to the history of contemporary world literature, and who were also your friends. Let us begin with the Italian writers.

First and foremost, it is the Italian authors, classics of world literature but also friends, who define the irregular and kaleidoscopic perimeter of that three-dimensional passeur that is Maurice Nadeau.

(1) For a reconstruction of Nadeau’s life, see Laure Adler’s interview book Maurice Nadeau. Le chemin de la vie (2011), the prefaces written by Tiphaine Samoyault for the first two volumes of Soixante ans de journalisme littéraire (2018; 2020) and the documentary made by Nadeau’s son, Gilles, entitled Maurice Nadeau. Révolution et littérature (2005). For a sociological analysis of Nadeau’s editorial choices from 1952 to 1990, I refer you to my work Tra politica, editoria e letteratura: Maurice Nadeau critico-editore (De Cristofaro 2025).

Bibliography

Marco De Cristofaro, “Between politics, publishing and literature: Maurice Nadeau, critic and publisher”, Studi francesi, no. 206, May-August, 2025, pp. 409-422

Marco De Cristofaro, “Pour vous j’ai existé”: the role of the passeur in the editorial memory of Maurice Nadeau, in M. De Cristofaro, F. Fossati, N. Sforza (eds.), Passeurs. Italian literature outside Italy (1945-1989). Reception and imagination, Faculty of Philosophy and Letters-University of Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires, pp. 120-134

Mario Fusco, Towards a history of Sciascia’s presence in France, in M. Simonetta (ed.), I do nothing without joy. Leonardo Sciascia e la cultura francese, La Vita Felice, Milan, 1996, pp. 37-44

Giovanna Lombardo, Sciascia e Nadeau. Di amicizia, agenti letterari, e passioni mai spente, in “Todomodo”, II, Olschki, Florence, 2012, 265-274

Jean-Yves Mollier, Paris capitale éditoriale des mondes étrangers, in Pascal Fouchet (ed.), L’édition française depuis 1945, Éditions du Cercle de la Librairie, Paris, 1998

Maurice Nadeau, Grâces leur soient rendues. Mémoires littéraires, Albin Michel, Paris, 2011

Maurice Nadeau, Le chemin de la vie. Entretiens avec Laure Adler, Verdier, Paris, 2011

Maurice Nadeau, Soixante ans de journalisme littéraire, tome 1, Les Années de “Combat” 1945-1951, Les Lettres Nouvelles-Maurice Nadeau, Paris, 2018

Maurice Nadeau, Soixante ans de journalisme littéraire, tome 2, Les Années de “Lettres Nouvelles” 1952-1965, Les Lettres Nouvelles-Maurice Nadeau, Paris, 2020

Maurice Nadeau, Soixante ans de journalisme littéraire, tome 3, Les Années de “Quinzaine Littéraire” 1966-2013, Les Lettres Nouvelles-Maurice Nadeau, Paris, 2022

Tiphaine Samoyault, Vers l’indépendance, in Maurice Nadeau, Soixante ans de journalisme littéraire, volume 2, Les Années de “Lettres Nouvelles” 1952-1965, Les Lettres Nouvelles-Maurice Nadeau, Paris, 2020, pp. 7-11

Philippe Schuwer, Nouvelles pratiques et stratégies éditoriales, in Pascal Fouchet (ed.), L’édition française depuis 1945, Éditions du Cercle de la Librairie, Paris, 1998