The Italian Book in Norway

Author: Siv Erle Wold, responsable des relations extérieures à l'IIC Oslo et traductrice de littérature italienne.

The history of literature in Norway begins relatively recently, and consequently so does the history of translated literature. Norwegian literature, in fact, flourished mainly from the second half of the 19th century onwards, after the four-hundred-year union between Norway and Denmark. Until then, the written language had been Danish, and Copenhagen was not only the political-administrative capital of the state, but also its cultural and literary capital. During the 19th century, Norway began to develop its own literature and language, and in particular a language called ‘Nynorsk’, or Neo-Norwegian, a form of writing that was closer to the spoken version of Danish, the ‘Bokmål – the language of books’. This is why to this day there are two official languages in Norway, in addition to the Sami language, both of which are also used in translations of foreign books. It was also in the 19th century when the first Norwegian publishing houses were first established. This little insight into Norwegian literary and linguistic history explains why the history of Italian books in Norway is rather short.

The first publications of Italian books in Norwegian appear mainly from the second half of the 19th century onwards. These include Giovanni Boccaccio’s Decameron, published in 1891, and Edmondo De Amicis’s Heart, first published in 1896 with a foreword from the publisher, which is interesting to quote: “The content of this book is for the most part so different from the experiences that children have here, from what they think to what they feel, that it would not, in itself, appear to be capable of fascinating a Norwegian boy. However, we believe there is much in this book that makes for a useful and enjoyable reading for our boys, so we wanted to publish a selection of its stories.” This passage is worthy of attention not only because of the freedom the publisher takes to not publish the entire book, but above all because it addresses an issue, that of the relevance of Italian books to Norwegian readers, which is still of crucial importance in publishers’ choices.

Among the publications of Italian works in the early twentieth century, we should of course mention Pinocchio by Carlo Collodi, which was published in Norwegian for the first time in 1921. Also in the 1920s, several novels by Grazia Deledda were published, such as Ashes and The Flight into Egypt, while Luigi Pirandello’s first work in Norwegian, The Late Mattia Pascal, was only published in 1935, a year before the writer’s death. Also worth mentioning is a small anthology of Italian sonnets published in 1943 under the title Fra Dante til d’Annunzio (From Dante to d’Annunzio), which includes, among others, Francesco Petrarca, Boccaccio, Ludovico Ariosto, Vittoria Colonna, Torquato Tasso, Ugo Foscolo, and Giacomo Leopardi.

The vicissitudes of Norwegian publishing during this ‘debut period’ of foreign literature in Norway are also worth mentioning. Among the oldest publishing houses (still maintaining their leading role in the Norwegian publishing world) are Cappelen (now Cappelen Damm) founded in 1829; Aschehoug, founded in 1872, and Gyldendal, which opened its own branch in Norway in 1925 (it was already an important Danish publishing house). All three devoted special attention to foreign literature, even if Italian has not always been among their priorities. In fact, if we look at Gyldendal’s 101 publications in the Den gule serie – The Yellow Series (so named for the colour of its cover) dedicated specifically to foreign literature, we find, in the thirty years of its existence from 1929 to 1959, only a small number of Italian works. It’s not until 1952 that we find an Italian title, Don Camillo by Giovanni Guareschi – an author which the publishing house continued to publish in later years. 1954 saw the publication of The Red Carnation by Elio Vittorini and Dinner with the Commendatore by Mario Soldati. The ‘yellow series’ then had a shorter second life, between 1962 and 1970, during which Dino Buzzati’s A Love Affair was published in 1964. By the same author, The Tartar Steppe (2001) and The Bears’ Famous Invasion of Sicily (2008) were published in more recent years, both translated by Tommy Watz and published by Solum Press.

After World War II, a number of volumes by some of Italy’s major writers of the time came out, including Elsa Morante’s Arturo’s Island (1959) and History (1974, and republished several times) and Alberto Moravia’s The Woman of Rome (1950), Conjugal Love (1951) and Two Women (1959). Other important titles by Moravia would only come out much later: his debut novel, The Time of Indifference, in 2012 (translation by Tommy Watz, awarded the prestigious Bastianprisen prize) and The Conformist in 2015.

Even the few works by Pier Paolo Pasolini which can be found in Norwegian came out much later than the original publications: The Poet of the Ashes in 2017, edited by Camilla Chams, and the selection of lyrics from Poem in the Shape of a Rose, in 2008 in Astrid Nordang’s translation.

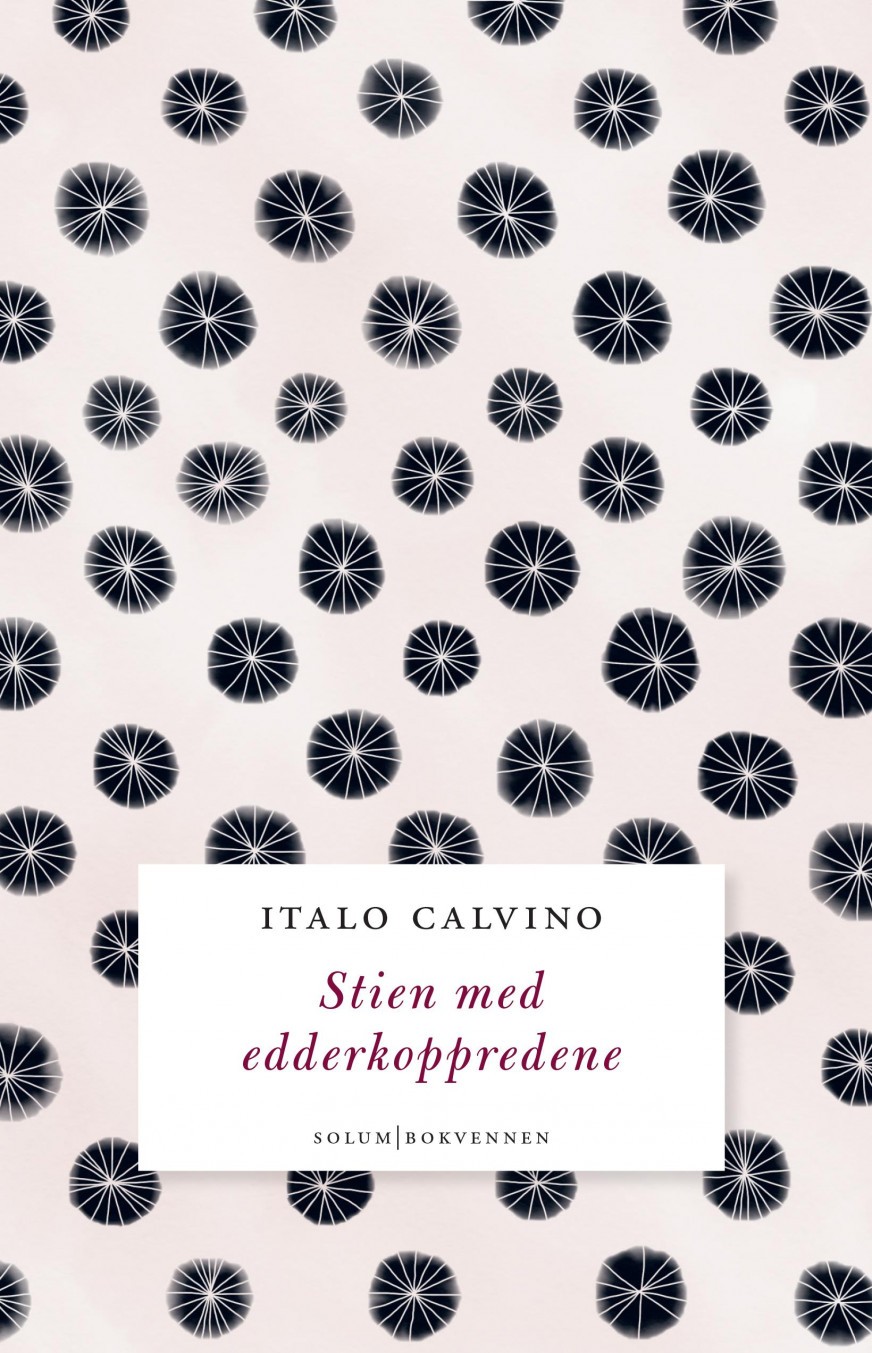

A large number of Italian writers were published between the end of the 20th century and the beginning of the new millennium. Of particular interest is the large anthology of short stories – mostly translated by Professor Magnus Ulleland in ‘nynorsk’ – entitled Italia forteller (Tales from Italy), published in 1994. Most of the authors collected here are from the twentieth century, but a small section is dedicated to writers from a more distant past, from Boccaccio to Bandello, from Gaspare Gozzi to Alessandro Manzoni. It should be noted, however, that even in recent years the number of Italian titles published in Norwegian is not particularly high. This may be due to market constraints or uninspiring sales results: the fact remains that Norwegian publishers seem reluctant to translate even internationally successful authors. Dacia Marini, for instance, an author much translated throughout Europe, is virtually unknown in Norway, and only one of her books is translated into Norwegian, The Silent Duchess (1994). Since it would be impossible to make an exhaustive list, we will only mention some of the most translated authors in recent decades: Umberto Eco (about ten titles); Claudio Magris (six titles); Italo Calvino, seven titles (interestingly, Calvino’s first book, The Path of the Nest of Spiders, is also the last to have been translated, in 2018). One or more books by the following authors have also been published: Milena Agus, Niccolò Ammaniti, Silvia Avallone, Alessandro Baricco, Giorgio Bassani, Paolo Cognetti, Erri De Luca, Donatella Di Pietrantonio, Claudia Durastanti, Fabio Geda, Simonetta Agnello Hornby, Diego Marani, Margaret Mazzantini, Melania Mazzucco, Alda Merini, Andrea Molesini, Michela Murgia, Carlo Rovelli, Umberto Saba, Leonardo Sciascia, Roberto Saviano, Antonia Pozzi and Patrizia Vicinelli. Authors like Andrea Camilleri, Giorgio Faletti, Roberto Costantini, and Ilaria Tuti are mystery and psychological thriller writers. As to graphic novels, the publication of Hugo Pratt’s complete works, translated by Jon Rognlien, is worth mentioning. Published by Det Norske Samlaget in the brilliant ‘Nynorsk’ translation by Kristin Sørsdal, Elena Ferrante’s My Brilliant Friend tetralogy was a huge success with Norwegian readers. As in the whole of Europe, the ‘Ferrante effect’ triggered a sort of cascade reaction in terms of interest for Italian books, and especially books set in southern Italy.

In recent years, renewed attention is being paid by Norwegian publishers to ancient and modern classics of Italian literature. For instance, between 2010-2020 Solum Bokvennen published works by Pico della Mirandola, Niccolò Machiavelli, and Baldassare Castiglione. At Det Norske Samlaget, a selection of tales from the Decameron came out in 2020, and recently two publishing houses, Dreyers Forlag and Solum Bokvennen, published Dante’s Inferno. The two other parts of Dante’s Comedy are also due to be published soon, translated by Erik Ringen and Asbjørn Bjornes. The Comedy will thus for the first time be translated in its entirety in the ‘Bokmål’ version – in no less than two different editions. There is also a 1993 version of Dante’s entire poem in ‘Nynorsk’, translated by Magnus Ulleland. As to 20th-century classics, we should note that five books by Primo Levi have appeared in the last decade at Dreyers Forlag, including The Periodic Table and The Drowned and the Saved, translated for the first time by Birgit Owe Svihus. More Primo Levi titles are announced to come out in 2022 and 2023. While in 2020 Skald Forlag published Luigi Pirandello’s, One, No One, and One Hundred Thousand, it’s especially Natalia Ginzburg who, among 20th century Italian authors, seems to be attracting the most interest from readers and the press: Family Lexicon was finally translated into Norwegian for the first time (a translation for which Astrid Nordang won the ‘Kritikerprisen’ prize), The Little Virtues was republished in 2021 and The Dry Heart was published in 2022.

In recent years several translators received critical awards, finding recognition for their fundamental role as promoters of Italian literature with the reading public and publishers in Norway: Brit Jahr (2005), Tommy Watz (2006), Jon Rognlien (2006) and Kristin Sørsdal (2020).