About some recent French translations of the Comedy of Dante Alighieri

Author: Lisa Amicone, Université de Liège

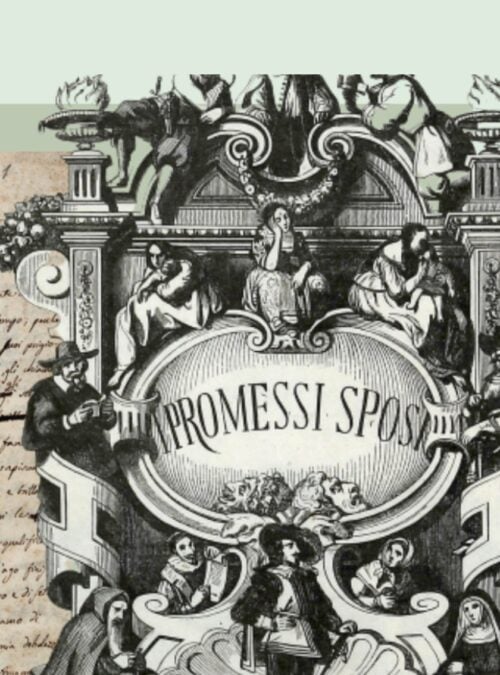

Even if rare at first, since it was necessary to wait until the 15th century to find a first translation – albeit partial – of the Comedy, the French translations of the Dantean work have known a great effervescence thereafter. Such effervescence has never diminished among French speakers, and even less so in this year punctuated by the celebrations in honor of the seven-hundredth anniversary of the death of Dante Alighieri. In fact, during this last decade, there have been about twenty publications of the Poem in French. It is important to consider that those translations all differ in their principles and results. The difference arises from the fact that it is impossible to transpose all the components of the Comedy – given the complexity of its content and form – and that, consequently, the translator must choose a key for reading and transmitting it.

The translation by René de Ceccatty – a prolific writer, critic and translator of Japanese and Italian – was published by Points in 2017. He chose what one could consider a “simplified” approach. His aim was to clarify the Dantean text through various processes, such as simplifying overly complex rhetorical figures, lightening repetitions, modernizing archaisms and preciosities, or clarifying or even deleting references to people or events that have become obscure to the reader today. This objective of “immediate readability” also includes the implementation of a “reductive system”, as the translator takes on the challenge of rendering the Dantean endecasillabo in the French octosyllable, which he finds “very musical and very flexible”, even if different from the original meter. Obviously, rendering Dante’s verses in only eight syllables is an imposing constraint that has pushed the translator to take many liberties with the original. Ceccatty confesses in his long preface The Eagle’s Eyebrows and the Summer Rain that his reworking of the primary material could be considered, at times, to be an “impoverishment”. A linear comparison with the source text will certainly show that the translation is different, but Ceccatty’s objective is respected: the reading is easy and not interrupted by a myriad of comments, as it had become the case of many translations produced until then.

Danièle Robert is also a writer, critic and translator, with a predilection for languages such as English, Italian, Spanish and Latin. Her Dantean translation enterprise has spanned ten years, with the publication of Hell in 2016, Purgatory in 2018, and Paradise in 2020. The first publications are all in bilingual editions, while the complete edition – published by Actes Sud in 2021 – does not mirror the original text. Like her colleague René de Ceccatty, Danièle Robert wonders how to render a modern reading of the Comedy, but proposes a different solution. She states that the Dantean translation must take into account “the structure intended by the poet, that is to say all the components of the work and, first and foremost, the third rhyme which is the seed from which it blossoms into a vertiginous arborescence[1]”. One must acknowledge Robert’s audacity, since she is speaking out against translation theorists who have long claimed that maintaining the rhyme in transposition is too difficult a constraint to respect. The same is true of the terza rima, whose respect in French is even more delicate, if not impossible, as Jacqueline Risset stated in the preface to her translation of the Comedy. The interest of this risk-taking is to remain faithful to the deep meaning of the text, since in Dante, the form – built notably on multiples of 3 – gives meaning to the content. It is interesting to note that the translator does not let herself bound up in an overly restrictive straitjacket, since she maintains that “all the rules set up mathematically as a system must bend to a higher rule, that of harmony […]”. This flexibility is also marked in her metrical choices, when she decides to render the endecasillabo by alternating décasyllables and hendécasyllables. Thus, even if Danièle Robert imposes a certain structure on herself, this structure does not hinder creativity, but rather stimulates it, making the act of translation an act of true creation. Finally, the translator is well aware of the complexity of the Comedy, which is why she provides the reader with numerous explanatory notes. These notes are placed at the end of the book so as not to prevent a “cursive reading”.

Michel Orcel’s academic and professional background sets him apart from his colleagues. With a background in political science, Islamology, and the humanities, Orcel focuses on the translation of numerous classics – including Roland furieux – and on poetic writing. The idea of tackling the Dantesque translation enterprise was prompted not only by his publisher Florian Rodari, who dreamed of offering a translation of the Italian masterpiece in the catalogs of the Dogana – a Swiss publishing house –, but above all by the translator’s “extreme irritation” caused by the latest Dantesque translations. Thus, in 2018 the translation of the first canticle was published, followed in 2020 by Purgatory and in 2021 by Paradise. The objective here was not to simplify the content of the Dantesque work – as was the ambition of René de Ceccatty’s translation – but rather to “render this journey all in contrarieties and harshness”. To do so, Orcel uses various tools such as “borrowings from Old French, […] elisions in use at the time”, neologisms or inversions, while taking care not to propose an archaic language. The choice he made regarding the explanatory notes is in the same line. Explanatory notes are reduced to a minimum and placed at the end of the volume; the translator considers that “the reading of the Comedy should almost do without notes”. Moreover, for Michel Orcel, there is no question of maintaining the terza rima in French, since according to him, “the battle is not engaged in the ending of the verses” – even if in the preface to Purgatory he admits that if he had done it again he would have tried to “increase the apparatus of the echoes” –, but rather in the rhythm. Thus, he opts for the French decasyllabic – the exact metrical correspondent of the endecasillabo, since the accent falls on the tenth syllable – which he handles skillfully.

From this brief presentation of the recent translations of the Comedy, it appears that the French reader enjoys the luxury of being able to approach the Dantean masterpiece from the perspective that suits him best and according to his desires. Obviously, it would be even more effective to read all these versions because, as Léon Robel says, “a text is the sum of all its significantly different translations”.

[1] For the sake of coherence and legibility, the quotes (originally in French) will be translated in or paraphrased in English.