Translation and artificial intelligence: interview with Paolo Bellomo

Author: Federica Malinverno

®Dimitri Bouchon-Borie

®Dimitri Bouchon-Borie

Paolo Bellomo is a bookseller from Bari, in southern Italy, who grew up navigating between the Italian spoken in the city and a rich constellation of local dialects. He has been living in Paris and working in French for almost fifteen years. His doctoral thesis in comparative literature was entitled “Translation put to the test of imitation. Translation, pastiche, thoughts on resemblance in France and Italy in the 19th and 20th centuries”. He enjoys translating novels, plays and poetry into Italian or French, most often with the help of four or more regular and willing collaborators. Pauline Peyrade’s play Con la carabina, translated by him, received two Ubu Awards in Italy in 2022. Since 2021 he has been a member of Outranspo (Ouvroir de Translation Potencial). In 2024 he published his first novel, Faïel & les histoires du monde, with Le Tripode.

You have a PhD in comparative literature: was it through your academic career that you became interested in translation?

When I embarked on this final stage of my academic career, I was already a translator. The PhD arose from a desire to understand the field I was working in. In my thesis, I conducted an archaeological study of translation theory in France and Italy from a Foucauldian perspective, attempting to identify the impensé, or the unthought, in various discourses on translation. I was also interested in the similarities between translation and imitation.

Had this translation work, undertaken both before and during your PhD, already led to any publications?

I always knew I wanted to be a translator, but when I started my PhD, I hadn’t published much yet. However, in terms of translation experience, I had this spectacular forge that was the theatre translation collective “La Langue du bourricot”, which I co-founded with Professor Céline Frigau-Manning and others at the Université Paris 8. Together with students, translators, directors, actors and theatre technicians, we translated Duetto by Antonio Moresco, as well as texts by Matteo Bacchini and Emma Dante, with unanimity as our rule.

What does being a literary translator from Italian into French mean to you? Has your academic training led you to develop a particular approach?

Publishers’ reactions to this profile vary greatly. Some value such a long course of study, as well as the prestige of having a PhD; others fear that academics translate in too academic a manner. Furthermore, my doctorate has given me a certain self-confidence and helped me to situate my work within the various translation trends and to defend my translation choices with greater knowledge.

Where do you stand in the debate on the development of Artificial Intelligence and changes in the work of translators?

For me, one of the most interesting aspects of translation is the experience of translating itself. Entering into the fabric of a text in another language, trying to identify its knots, understanding how to pull them, how to untie them, how to loosen them and then re-tie them in the target language, is one of the most beautiful things ever. It is a continuous forge in which you never stop learning. When you do it collectively, the pleasure of this experience is doubled, even if the finances are halved. It’s like when you work in the theatre, you create a kind of collective language, a kind of “delirium” about the text that makes you exist in the language in a way that, until then, you did not exist. And the text inhabits you, it enters your flesh even more than it enters the flesh of the reader. So we translators are very privileged readers. From a practical point of view, if publishers start relying on AI, not only do they deprive translators of the experience I mentioned, but they also deprive themselves of the quality of the translator’s work. If they then assign a good translator to revise a text translated by AI, in the end, little time is saved, the work is more alienating, and the result is still worse than a text translated solely by a human being. Most of the time, when AI cannot solve something, it produces a text that is apparently coherent, so it requires much more attention, and it also creates biases, i.e. it steers the translation in a very normative direction. Literature, on the other hand, delves deeper, sometimes against the linguistic norm. So, a good translator basically finds themselves undoing the work of AI.

Are you concerned about the impact that AI is having and could have on the world of translation?

In my opinion, translators and publishers will have to sit down around a table and discuss these issues so that the presence and ease of AI does not become something that weighs on the remunerative balance of translators’ work. Because that is the beginning of the end. I am not so much afraid that artificial intelligence will be able to translate like humans, because I do not believe that will happen. Rather, I am afraid that we may end up settling for something that is “not so bad”. And for me, that would be the death of literature and the profession, not only of translators, but also of publishers. Because perhaps this savoir-faire of building editorial lines – which is still the prerogative of human beings, publishers and translators… – perhaps, at some point, the financial directors of publishing houses will delegate this work to AI. So, if my profession is in danger now, it means that others will be too, because everything is interconnected. And so, all the more reason to sit down together and defend these professions.

Returning to your profession as a translator, are you always able to translate texts that interest you and that you like? If so, how do you do it?

Since I started this job, I have always done other things as well, so I have been very privileged: for now, I have translated almost exclusively books that I liked. In the French-Italian market, literary agents are very active: my added value therefore lies in seeking out titles that have gone unnoticed in the publishing world, not just in Italy but internationally, for example during the Frankfurt Book Fair. My work as a bookseller also gives me insight into and visibility of the editorial lines of French publishing houses. To give you an example, last year I read Inventario di quel che resta dopo che la foresta brucia (Inventory of what remains after the forest burns) by Michele Ruol [TerraRossa edizioni, 2024], which I found not only to be an excellent book, but also a book suitable for the French market, and I proposed it to Le Tripode. They trusted me and bought it months before it became a finalist for the Strega Prize.

What criteria do you use to choose the Italian books you propose in France?

Since becoming a bookseller, I have become a very eclectic reader, and my taste palette has expanded greatly. However, when I read a text, there is a kind of encounter that either happens or doesn’t happen. Let me explain: I may like a text as a reader, but it does not necessarily trigger what Berman calls the translational impulse, that is, the desire, the existential need to translate it.

Then there are books where the translation experience may be less exciting, but which give me work. So I don’t just focus on books that trigger the impulse.

Can you tell us about your experience of self-translation? What did it mean to you?

Self-translation [i.e. translating Faïel et les histoires du monde, Le Tripode, 2024, Ed.] was not necessarily an experience I wanted to have. It was at the invitation of Fandango [the Italian publisher, Ed.] and I asked myself, ‘Why not? I told myself: “Translate as if it were someone else’s text, i.e. maintain the same distance from your text”. But, in that case, the text was so familiar to me that I couldn’t experience it as a stranger, and I had the impression that the final text was a kind of papier-mâché text, which moved in jerks that were not very credible. I had to put myself in a kind of trance, and I don’t usually do that when I translate. It was very strange, but I wouldn’t say it’s a rewriting, for me it remains a translation: I rewrote very little and mainly sentences that didn’t work for me in terms of rhythm.

Besides, it had been a long time since I had written in Italian, and with such a high level of poetic demand. It felt like I had finally found an old friend again, my language, and it was wonderful.

You have also often experimented with four-handed translation. What has that experience been like?

If it weren’t so hard financially, I would only do that, especially because of the “delirium” around the text I mentioned earlier. Furthermore, four-handed translation is something that strengthens the text, because it allows you to see yourself in the mirror and become more aware of your translation choices. And, above all, it allows you to shift and re-evaluate your linguistic taboos, to understand that your mastery of the language is relative.

Do you think France pays particular attention to contemporary Italian fiction today?

It depends on the publisher, but I think there is a lot of attention. For example, it is very difficult to find a repêchage that has not already been evaluated by the French publishers you are targeting. For me, we translators, agents and scouts have a duty to try to shine a spotlight on authors who have not yet been “seen” by the market but who deserve to be. Beyond economic imperatives, there are publishers who make courageous choices. We talked earlier about Ruol, which has now sold about 15,000 copies, but when I proposed it, it had sold about 1,000. The search for stereotypes, on the other hand, seems to me to be confined to book covers. I have seen books written by authors from southern Italy that were not set by the sea but had a beach on the cover. However, I think this is more a form of marketing than an active search for texts that convey stereotypes.

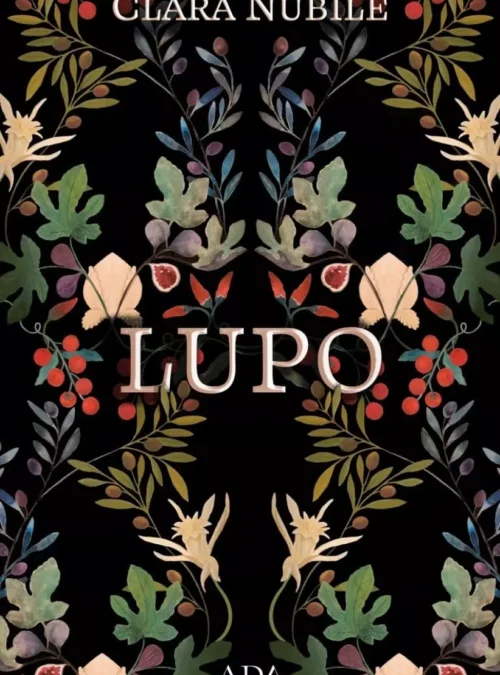

To conclude, a question about the past and one about the future: can you talk about the Italian books you have translated and what they have left you with? And what is a book you would like to translate?

Well, among the books of the past, there is Alessandro Robecchi, the series starring Carlo Monterossi [Edizioni Sellerio; in France: Éditions de L’Aube]. For me, it was a great source of work on the technique of humour. I translated it with Agathe Lauriot dit Prevost, who has this sensitivity in her. From Robecchi’s translation, I came away with much stronger shoulders when it comes to translating humour. And it’s a direction I’d like to continue exploring. The most incredible translation experience was the two volumes of Fifty Fifty. Warum e le avventure conerotiche e Saint’Aram nel regno di marte by Ezio Sinigaglia [TerraRossa edizioni, 2021], translated into French as Les aventures érotiques de Warum & Saint Aram for Emmanuelle Collas editions [2025] together with Cécile Raulet, because I think Sinigaglia is one of the best living Italian writers. He is special in his anachronism, because he is a 20th-century writer whom we are publishing in the 21st century because for years he did not want to be published. Sinigaglia works with language in such a playful, irreverent and subtle way that he explodes language, reinventing it. He works so much in what Barthes would call the “feuilleté du langage”, this intra-language, this verve, that translating him forces you to reproduce that work which, incidentally, is the same as that towards which my neuroses tend. As for the future, there is a book that I love very much and that I find extraordinary that someone in Italy had the courage to publish, an extremely anachronistic book: Lo splendore by Pier Paolo di Mino [Laurana, 2024]. More than 700 pages, for the first volume of seven, which represents a considerable challenge for a foreign publisher. A European fresco that returns to the problem of the salvation of humanity, of good and evil. It is the work of a mystic, with an enchanting rhythm and a pronounced taste for the romantic. It is a text that needs to be supported and strenuously defended by the publisher who chooses it but, in my opinion, it is one of the most interesting works to have come out in Italy in recent years, a work that could become a classic of Italian literature. Finally, another title I would very much like to translate is Popoff by Graziano Gala [2024, minimum fax], a novel for adults that plays with the codes of children’s nursery rhymes and gives rise to images of great poietic and evocative power, a small but important gem, the second work by an author who will go far.