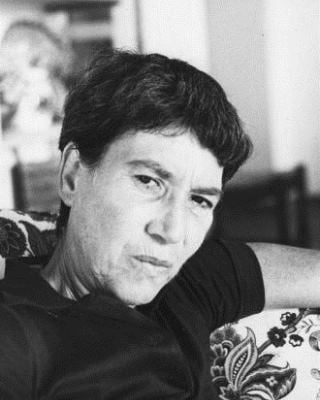

England has rediscovered Natalia Ginzburg

Author: Tommaso Munari

This article appeared on the Sunday supplement of the “Sole 24ore” on the 5th of April 2020. By kind permission of the “Sole24ore”.

In the spring of 1959 Natalia Ginzburg moved to London, where her husband, the Anglicist Gabriele Baldini, had been asked to direct the Italian Cultural Institute. He settled at 13 South Terrace, an elegant street in Kensington, a short walk from the Victoria and Albert Museum. During her stay in the British capital, she was visited by some Italian friends, such as Delio Cantimori and Lalla Romano, and she also maintained correspondence with others, including Italo Calvino and Luciano Foà. In terms of literary creation, it was a fruitful period. She wrote some reports for “Il Mondo” (La Maison Volpè, Elogio e compianto dell’Inghilterra – Eulogy and Lamentation of England), an essay for “Nuovi Argomenti” (Le piccole virtù -small virtues) and one of her most famous novels (Voices in the Evening), which Calvino praised for its sense of familiar stories, the rigor of the narrative and the geographical deepening: «This Piedmont, now that you are away – he wrote to her on May 12, 1961 -, while before you always generalized and toned it down, now it comes out of from all your pores».

Although after two years of living the London life she had developed a sort of impatience with the dull and monotonous food, the smell of dust and coal and the profound melancholy of its inhabitants (“England will not see me again for quite some time,” she wrote to Calvino on the eve of her return to Italy, May 23, 1961), she was positively impressed by some English characteristics: civilization, good governance, respect for others and hospitality: “It is a country – said sixty years before Brexit – which has always welcomed foreigners” (Elogio e compianto dell’Inghilterra). But the biggest surprise was literary. On the counter of a bookstore she discovered Ivy Compton-Burnett’s novels. She began to read them and fell head over heels in love with them.

In the early months of 1960 Ginzburg repeatedly recommended the works of this “strange and funny” writer, with her own way of making the reader live in the midst of certain family tangles” to Foà, who had asked her to report the most interesting editorial news, on behalf of Giulio Einaudi. Amongst the novels, “all dialogues, where the action comes out in tears, between one joke and another”, she recommended, in order, Mother and Son (1955), A House and Its Head (1935), Manservant and Maidservant (1947) and Elders and Betters (1944). Her infatuation with this author (“I would have liked, for a moment, to have been held in her gaze”, she wrote in the obituary that she dedicated to her in the “Stampa” on December 7, 1969) was so profound that she applied as a translator and she planned to invite her to dinner. She did neither, but Ivy Compton-Burnett’s novels became a her literary style model.

By happy coincidence, while Italian readers are now rediscovering Ivy Compton-Burnett’s books, thanks to the Fazi publishing house (More Women than Men, released in 2019, The House and its Head which has just been printed, other titles will soon follow), English publishers are doing the same with Natalia Ginzburg. The direct merit of this rediscovery lies with Daunt Books, the most refined bookstore chain in London. Indirectly, Elena Ferrante’s international success has also rekindled the foreign reader’s attention to twentieth century Italian fiction, especially female authors, as shown by the translations of Deviation by Luce d’Eramo (by Anne Milano Appel, Pushkin, 2018 ) and Arturo’s Island by Elsa Morante (by Ann Goldstein, Pushkin, 2019); and the publication of the surprising Penguin Book of Italian Short Stories (2019) in which the curator, Jhumpa Lahiri, has included eleven tales of writers, including the immature and cruel My Husband by Natalia Ginzburg.

In relaunching her books on the British market, Daunt Books has resorted to old and new translations, with original kaleidoscopic covers, and has presented them to the best known English novelists. Each of them has found a piece of themselves in Ginzburg. Starting with Tim Parks, who traces in Lessico Famigliare (Family Lexicon, translation and notes by Jenny McPhee, 2018) a literary confirmation of what he has learned and written about Italy over more than thirty years: the intimately relational identity of Italians. For her part, Rachel Cusk sees in the author of the Piccole virtù (The Little Virtues, translated by Dick Davis, 2018) a teacher of objectivity and distancing and a sensitive interpreter of issues dear to her, such as the relationship between writing and motherhood or, more generally, between narration and the self. By presenting Voices in the Evening, translated by DM Low, 2019, Colm Tóibín instead inserts Natalia Ginzburg into a constellation of English-speaking writers to whom he is indebted: Katherine Mansfield, Elizabeth Bowen and Muriel Spark (but he failed to mention the alpha star: Ivy Compton-Burnett). Finally, Claire-Luise Bennett focuses on the urgent and impulsive literary vocation that she feels throbs in every word of Caro Michele (Happiness, as Such, trad. By Minna Zallman Proctor, 2019), even the most ordinary and domestic.

Some devoted readers of Natalia Ginzburg might find the interpretations offered by these novelists be a little too casual, but it would be wrong to dismiss them hastily. Not only because they reveal the her international appeal, but also because, by drawing her closer, they draw her closer to the English public. And if it is true that none of them fully grasp the subtle passage from neorealism to bourgeois narrative that takes place in her works, nor do they fully grasp that particular historical movement that is hidden in “family lexicon”, it is equally true that, thanks to these four translations, her voice as a writer reaches English readers “with absolute clarity between the veils of time and language” (Rachel Cusk), while her books now glint in the windows of those avenues where, half a century ago, whilst spying on old women walking, she dreamed of running into Miss Compton-Burnett.