Italian books in Hungary –

Part one

Author: Margit Lukácsi, Katholische Universität Pázmány Péter in Budapest

At the beginning of the 20th century, an extraordinary generation of writers and poets, who were also great translators, emerged in Hungary. Italy was often the destination of choice for their journeys of cultural exploration, and their voices found expression in the pages of the famous review Nyugat, whose title means ‘West’ in Hungarian.

Nyugat‘s aim was to bring the main currents of modern and contemporary literature to Hungary and, through the translation of quality literary works, to cultivate the excellence of the national language. A whole generation of Hungarian poets and writers, from Babits to Kosztolányi, from Gyula Juhász to Árpád Tóth, right up to the younger Lőrinc Szabó, Attila József and Miklós Radnóti, devoted themselves to this programme. It was precisely the prestige of the translators that guaranteed the magazine’s authority. For at least half a century, Nyugat‘s cultural programme guided not only the development of the Hungarian literary language, but also the formation of literary taste, and it contributed to the formation of a solidly structured literary canon.

The most important achievement of the first half of the 20th century was undoubtedly the complete translation of the Divine Comedy into tercets by the poet Mihály Babits, who also wrote a prestigious history of European literature. For an entire century, this translation was a landmark for Dante studies in Hungary and a key event in the history of relations between Hungarian poetry and Dante’s work. It took almost a century before, after partial attempts by various poet-translators, another poet, Ádám Nádasdy, published a new complete translation of the Divine Comedy in iambic verse in 2016, enriched with a commentary adapted to the needs and culture of today’s audience. Centred on the binomial ‘fidelity and beauty’, the influence of the translation theory developed by the Nyugat review has been so strong that every Hungarian translator still finds themself confronted with this legacy in their work today, if only to deny it, accept it or mitigate its significance.

It is also worth mentioning that during the interwar period, as a result of official agreements fostered by the friendly relations between Italy and Hungary, an institutional network of cultural relations was created: the Hungarian Academy was founded in Rome, several university chairs were established, Italian-Hungarian cultural associations were organised and exchange programmes were launched, which gave rise to a mutual interest in the national literary productions of each country.

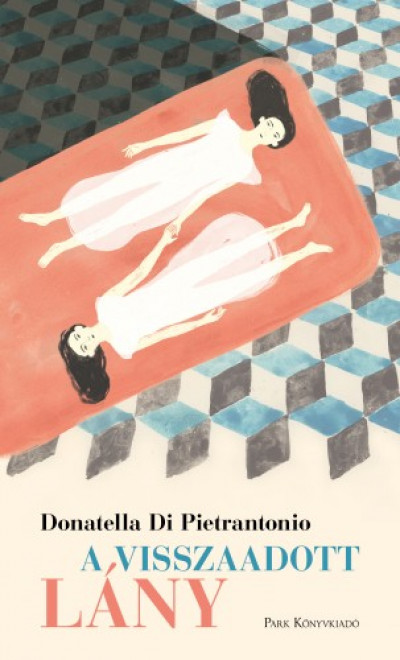

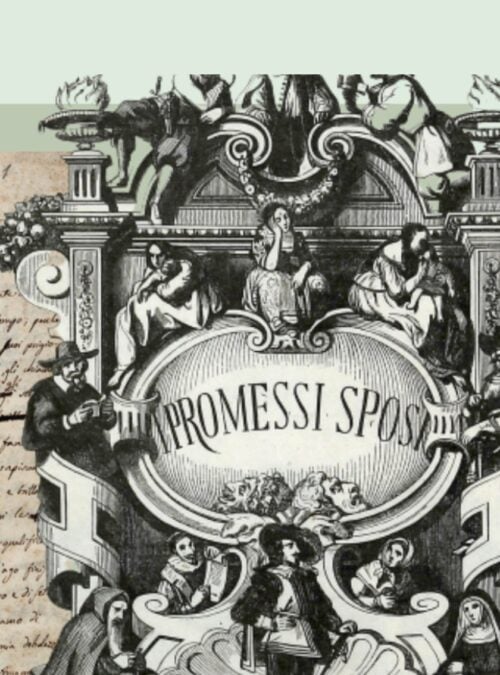

Another important moment in the process of opening up cultural horizons in the last century was undoubtedly the period following the Hungarian revolution of 1956. After 1945-1955, a decade of ideological closure for Hungary, the 1960s saw a revival in the publication of translations from so-called “Western” languages. Hungarian publishing, albeit with a certain delay, succeeded in providing a more balanced image of contemporary Italian literature. Authors such as Italo Calvino, Cesare Pavese, Elio Vittorini, Goffredo Parise, Natalia Ginzburg, Elsa Morante, Alberto Moravia, Dino Buzzati and Italo Svevo were translated and published for the first time, while classics such as Giacomo Leopardi, Giovanni Pascoli and Luigi Pirandello were republished.

Immediately after 1956, a number of important publishing initiatives were launched, including the founding of the monthly periodical Nagyvilág (The Big World), which, with its symbolic title in the style of the review Nyugat, was already proclaiming its main vocation. In the 1960s and 1970s, poets such as Umberto Saba, Giuseppe Ungaretti, Eugenio Montale and Cesare Pavese were translated, although it should be pointed out that editions of contemporary Italian poetry in Hungary have always been, and continue to be, somewhat inadequate.

The publication of Umberto Eco‘s Il nome della rosa (1988), followed by translations of all the author’s works, led to more general attention being paid to contemporary Italian literature. In the wake of the worldwide success of Eco’s novel, the number of Italian literary works translated into Hungarian increased year on year. After the change of regime between 1989 and 1990, countless publishing houses sprang up in Hungary, most of them condemned to a short-lived existence due to the competition fuelled by the economic mechanisms of the new market.

Sometimes it’s not just an author or a book, but also a person who plays a key role in mediating between cultures. It was certainly the appointment of Giorgio Pressburger as Director of the Italian Cultural Institute in Budapest that gave a major boost to the development of Italian-Hungarian cultural relations. In the years from 1998 to 2022, during which the Hungarian naturalised Italian writer and director held this post, Italian culture enjoyed unprecedented success in Hungary thanks to numerous initiatives (theatre performances, operas, major exhibitions of artists such as Savinio and Campigli, book presentations, etc.). Giorgio Pressburger also created a collection of contemporary Italian literature, “Palomar”, designed to include works and/or authors that had never been translated in Hungary: a unique publishing initiative, offering readers bilingual editions with the original text and translation alongside each other. Hungarian readers were able to discover authors such as Tommaso Landolfi, Alberto Savinio, Antonio Delfini, Silvio D’Arzo, the prose of Umberto Saba, Carlo Emilio Gadda, Francesco Masala, Paola Capriolo and Daniele Del Giudice. Many important voices of contemporary Italian literature, some of whom have yet to be fully appreciated by Italian readers, have made their appearance in Hungary.

In 2002, the year Pressburger stepped down as director of the Italian Cultural Institute, Italy was chosen as the guest country at the Budapest International Book Festival, further broadening the horizons of Hungarian readers interested in Italian literature. Guests of honour at this festival, which is an increasingly important yearly event, have included Umberto Eco in 2007 and Claudio Magris in 2012. In 2013, for the first time in the festival’s history, Italy returned as the guest country. All this might suggest that Italian literature in Hungary has a prominent place. It would be more accurate to say that there have been years when it has received special attention, as also shown by the increase in the number of translations. We have already mentioned the case of Umberto Eco, whose novels and most of his essays have been translated. Claudio Magris’s most important and interesting works on Central Europe have also been translated: Danubio, Un altro mare, Microcosmi, Alla cieca.

The round table discussion with emerging writers is a highlight of every Festival. L’Harmattan, a French publishing house that also has a presence in Hungary, has created two series devoted to contemporary foreign literature, with a particular focus on Italian authors, some of whom were invited to the Book Festival. These include Giorgio Vasta (Il tempo materiale, 2013), Alessandro Mari (Troppo umana speranza, 2016) and Giuseppe Lupo (Viaggiatori di nuvole, 2016).