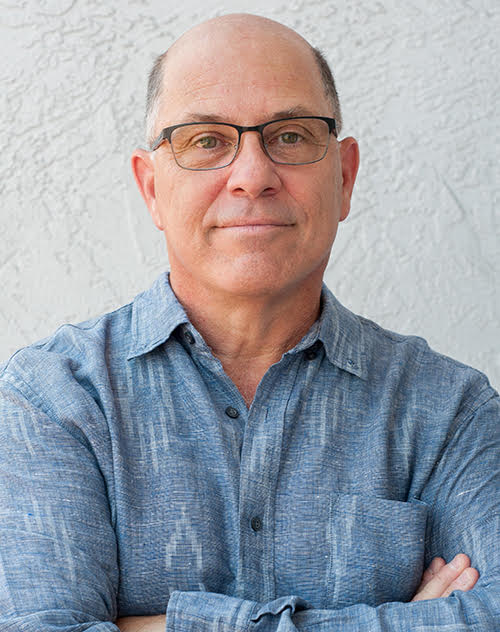

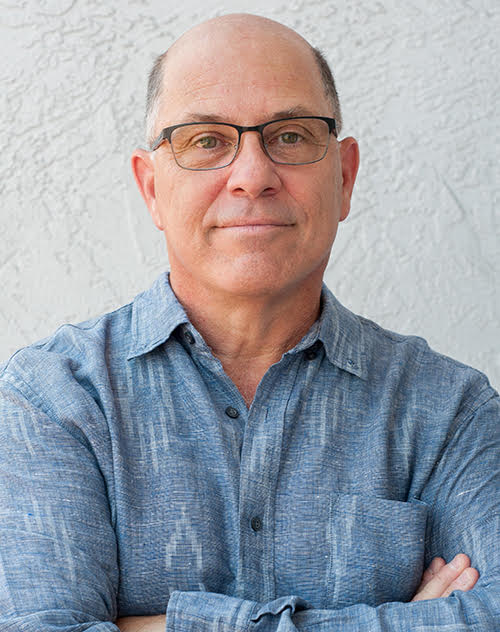

Interview with Antony Shugaar, writer and translator

Antony Shugaar is a writer and a translator from the Italian and the French. He’s translated dozens of articles for the New York Review of Books and close to forty novels for Europa Editions. He has translated many novels that were awarded Italy’s highest literary award, the Strega Prize (the 2011 winner, Edoardo Nesi’s Story of My People, Resistance Is Futile, by Walter Siti [2013], Francesco Piccolo’s Wanna Be Like Everyone [2104], Ferocity, by Nicola Lagioia [2015], and the 2016 winner, The Catholic School, by Edoardo Albinati). In the realm of Italian noir, aside from some of the work of Gianfranco Carofiglio, he’s also translated books by many of the leading figures in the field: Massimo Carlotto, Sandrone Dazieri, Maurizio de Giovanni, the late Giorgio Faletti, Antonio Manzini, and others. He’s received two National Endowment of the Arts fellowships. He translated two books in the W. W. Norton Collected Works of Primo Levi, published in 2015. And his translation of Hollow Heart by Viola Di Grado was shortlisted for both the PEN and the ALTA Italian translation awards. He has translated TV series and movies for HBO, Netflix, and Amazon.

In your CV, you describe yourself as a writer and a translator. How important has each of those activities been in your past and present professional life—what percentage of your work is writing, what share is translating?

I love writing and I love translating. But I seem to have found my way into a particularly happy niche as a literary translator. I’ve done more than forty books for Europa Editions. At a modest count, I’ve done at least another hundred books over my career, and other material of various kinds, ranging from scripts and screenplays for TV and movies to advertising campaigns and all sorts of odd bric-a-brac. In particular I remember working with an investigative journalist on the story of how Giancarlo Parretti bought MGM in the 1990s. The headline was “How an Italian Thug Looted MGM, Brought Credit Lyonnais to Its Knees, And Made the Pope Cry.” Now that was fun. I have also done hundreds of articles and a couple of books in my career. Also fun. Generally speaking, though, journalism leads to financial problems. I tend to over-research. I also believe that good translation involves grueling research.

How did you become a translator? And why has your work as a translator been focused on the Italian language in particular?

I love Italy. Frankly, I love Mediterranean Europe. To me that means France, Italy, and Spain. I love language. My father knew seven languages. I might come close to that if you include some languages I don’t exactly speak: ancient Greek and Latin. It would be a stretch. He would speak to me in Italian as a child, and I really liked it. I visited Italy as a teenager, with family, and then moved there when I was 20. Complicated situation, but a nice outcome. I turned twenty-one at a dinner with my new employers at a translation studio in Cuneo. I was working as a translator to try to stay in Italy. My employers took me out to dinner in a small restaurant in Peveragno, if I’m remembering correctly. We had ravioli, and at one point I decided to count the number of ravioli across the bowl and multiply by pi. That was 7 ravioli times 3.1415, or 21.9905 ravioli. There really were 22 ravioli in the bowl! My employers told me that I had just committed an “americanata” and was completely missing the point of ravioli. But in a strange and primitive way, I feel I was on the right track. You have to look at the world of your “source” language and eye it appraisingly, measuring it and gauging its dimensions for the heavy labor of moving it all into a different, “target” language.

The great translator Richard Howard once wrote, on the topic of “Professionalism,” quoting Columbia University professor Justin O’Brien, “No one wants to be a professional translator.” I’ve always loved that quote. O’Brien translated Camus and Gide. When he died, regrettably young, O’Brien’s department chair had the following to say about him: “He was the kind of man who was a scholar with a human personality. He made friends.” That’s actually a very nice epitaph. And it’s a good description of the sort of adventure that translation is. It’s a little bit like an adventurous science fiction movie. No one ever wants to wind up caught in a tesseract, or be kidnapped by Martians. But once it’s happened, you just have to fight the fight. In a way, translation feels like you’re breaking some of the basic laws of physics. Taking meaning from its linguistic cradle and growing it in another medium just feels odd, like a form of contortionism. There is a famous quote, in English: “The past is another country. They do things differently there.” Very true. And if you consider that translation is taking an experience — because a novel is experience made flesh — then you’re doing something with translation — moving mind and experience from one language to another — that sort of resembles time travel. It’s transgressive, and strangely fun. It’s also a lot of work. Luckily, I’m paid for that work.

What do you think of the current state of affairs in American publishing with respect to Italian books? Have things changed in recent years? Is there more translation being done? Less? What publishing houses are paying the most attention to Italian authors? What authors are best loved and why?

Obviously, Europa Editions is doing a great deal of work. Outside of Europa, there are a scattered array of publishing houses. Farrar Straus, Norton, Quercus, Other Press, the list could — and does — go on. But really you’d have to look at the author. I’m not sure that publishers look at an author as an Italian author as much as they look at them as an author, plain and simple. Translation, if anything, is just an extra obstacle to publishing. I’ve long thought that editors have a secret equivalent to the Hippocratic Oath that doctors take, which famously begins: “First, do no harm.” The Editor’s Oath would begin: “First, don’t publish the wrong book.” Books are expensive to make, and there are more books than could ever be published. Flannery O’Connor once said: “Everywhere I go I’m asked if I think the university stifles writers. My opinion is that they don’t stifle enough of them. There’s many a best-seller that could have been prevented by a good teacher.”

You’ve translated such twentieth-century Italian classic authors as Primo Levi, but also a great many contemporary authors, among them Edoardo Albinati’s massive volume, The Catholic School, (1600 pages) but also books by Walter Siti, Nicola Lagioia, Francesco Piccolo, Edoardo Nesi, Roberto Saviano, Valeria Parrella, Davide Enia, Silvia Avallone, Maurizio De Giovanni, Carmine Abate, Massimo Carlotto, Andrea Molesini, Sandrone Dazieri, Giancarlo De Cataldo, Francesco Pecoraro, Gianrico Carofiglio, Diego De Silva, and more. What do you think of the Italian literature of recent years?

You might as well ask a fish what it thinks of water. I swim in it, I like it very much, I need it to live, and in a way I don’t know anything about it. I’m not here to know about it, I’m here to embody it.

How important is it for you, and for your work as a translator, to have a personal relationship with the authors of the books that you translate? While you’re translating their books, do you correspond with them?

Much less than you’d think. I do ask questions, but hopefully, the writer has put all the information there in the form of words. That said, when I do correspond with writers, I often discover just how many mistakes I make. Translation is about loss, intrinsically. You can’t salvage everything in a translation. To know the writer is to know someone you’ve betrayed but also rescued. It’s complicated and stressful.

Among the many Italian books you’ve translated, was there one in particular that presented an especially difficult and stimulating challenge?

The only really hard book to translate is a dull book by an uninteresting mind. You’re going to spend a long time with a book you translate, you’re basically going to climb into their mind and settle in for a long journey. So you just hope you’ll have something good to read for the ride, you know? I enjoy translating authors who take chances and who warp the fabric of reality with their imaginations. One of the hallmarks of that kind of author is that their writing always looks much more straightforward than it really is. When you translate a book, you really come to terms with the mechanics of the sentences and paragraphs. In a way, it’s like fixing a car, taking it apart and putting it back together. Well, with the writers I love, it’s as if there’s more than one engine in there, or else pistons moving in opposite directions on the same crankshaft, or parts that should be made of metal that are instead ingeniously crafted out of silk or bamboo.

And, no, I’m not naming names.

You have a long career as a translator behind you, almost fifty years. And you’ve also written articles and essays on the topic of translation. What advice would you give to a young person interested who wanted to get started in this career?

Translate. Translate everything. I learned a wonderful thing from my art history professor at Perugia, the “university for foreigners” where I studied many long years ago (nearly half a century as you remind me). Professor Pietro Scarpellini taught us that when Michelangelo and Raphael were young, they were set at a very early age, five or six years old, to grind paint. This meant roots, rocks, and all manner of things used for pigment. They sat there grinding away, until they had the exact desired hue. In Italian, there’s a useful saying, “Sbagliando si impara.” You learn by doing things wrong. They weren’t allowed to touch a brush until age 12 or so. So translate things of all kinds. If you want to make a living as a translator, don’t turn your nose up at anything. But do your best. You WILL make mistakes. After fifty years, I make LOTS of mistakes. But I try to get things right. And I keep learning from my mistakes, which are legion.