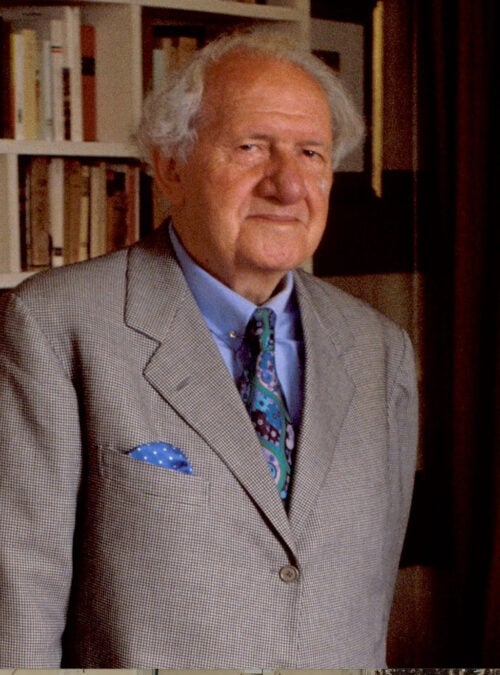

Leonardo Sciascia in other languages

Author: Paolo Squillacioti, CNR

Leonardo Sciascia (1921-1989) started to make a name for himself abroad when he was still little-known in Italy. He mentioned this himself in an interview he gave to the magazine Il Caffè politico e letterario, which introduced him to the Italian cultural world in April 1956: “A booklet of mine on Pirandello was translated into French, but I have no idea what they said about it. In America, it seems that they quite liked it”. The booklet was Pirandello e il pirandellismo, published by Salvatore Sciascia (not related) in Caltanissetta in 1953. This apparent indifference probably hides an intimate satisfaction, though it does confirm Sciascia’s revulsion toward his entire production prior to Parrocchie di Regalpetra, published in 1956 (translated in the USA in 1969 and in France the following year).

Sciascia’s real fame abroad began a few years later, however, following the publication of his most successful novel, Il giorno della civetta (Einaudi, 1961), translated in France in 1962, in the USA the following year (with the infelicitous title Mafia vendetta), and then in Romania, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia and Sweden. His second novel, Il Consiglio d’Egitto (Einaudi, 1963), was not translated quite as quickly, but was still translated into several languages: in Romanian and English (The Council of Egypt) in 1966, and in Hungarian and German in 1967. The Swedish translation of his third novel, A ciascuno il suo (Einaudi, 1966), was published in the same year as it came out in Italy, and was then published in Spain in 1968 (in both Spanish and Catalan) and, later, in Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, the United Kingdom and Germany.

From this brief overview of Sciascia’s initial success abroad, what is clear is the great interest in an author who, initially, devoted himself almost exclusively to a very peripheral area, Sicily. What this overview does not reveal is the important role that France played in Sciascia’s success in Europe. It is worth taking a closer look at this.

Sciascia had always displayed a marked preference for French literature and French culture, as revealed by his numerous visits to Paris and his decision to move to the French capital, even though, in the end, he did not move there. Moreover, as a writer, he felt that he was only truly understood by French scholars like Dominique Fernandez, Philippe Renard, Mario Fusco and, above all, Claude Ambroise, whom Sciascia used to refer to as “his” critic. And it was thanks to the work of scholars of Italian origin, such as Fusco and Jean-Noël Schifano, that the entire production of this Sicilian writer was translated into French, not only individual works, but also the enormous collection in three volumes put together by Fusco between 1999 and 2002 – a French version of Opera, painstakingly assembled for the publishers Bompiani by Ambroise between 1987 and 1992. This proved decisive in cementing Sciascia as a classic writer in twentieth century European literature as in France, too, the dominant vision of Sciascia that had been forming was anchored to the controversies of the end of the 1980s and the posthumous controversies of the early 1990s. This publication of the writer’s entire production made it possible to correct this deformed, partial image on the part of French critics.

France, together with Spain (where Sciascia’s almost entire production has been translated), remains one of the European countries to show the greatest interest in the writer. The recent interest shown is not limited to his canonical works, carefully put together in the Bompiani edition and since re-edited using philological criteria by Adelphi (2012-2019), but also includes his lesser-known works, which Adelphi has been collecting for almost 20 years. I am thinking, in particular, of the French translation by Carole Cavallera of the collection of essays on Stendhal compiled by Sciascia’s widow Maria Andronico, L’adorabile Stendhal (Adelphi, 2003), recently published in France with the title Stendhal for ever. Écrits 1970-1989 (Cahiers de l’Hôtel de Galliffet, 2020).

Sciascia’s success in Europe has been the subject of considerable attention. In addition to various conferences, there is a specific series of the Florence publishers Olschki, “Sciascia scrittore europeo” (three volumes published since 2011 on his success in Switzerland, Yugoslavia and German-speaking countries). There are also many articles in the international journal of Sciascia studies, Todomodo, also published by Olschki, that have looked in detail at how Sciascia’s work was received in countries all over the world, from Spain to Japan, China to the Arab-speaking world, and Poland to the United Kingdom.

To have a very brief, but still clear idea of his popularity, one need merely look at the section “Opere tradotte” (“Translated works”) in the Bibliografia degli scritti di Leonardo Sciascia, edited by Antonio Motta for Sellerio and published in 2010 (where the translations are listed in chronological order) and at “Biografia delle traduzioni” (by Frans Denissen) in Verità e giustizia. Leonardo Sciascia vent’anni dopo, edited by V. Lo Cascio and published by Academia Universa Press in 2009 (where the translations are organised in the order in which the original works were published).

The many studies reveal that Sciascia has been translated at a planetary level and that any attempt to produce some kind of summarisation would merely result in a list of titles, languages and dates. I prefer to highlight that his success internationally basically demonstrates the broad, general interest in his works. There have also been cases of censorship, as would be expected of an author who managed to upset all those expounding ‘official’ and ‘unquestionable’ truths, while stimulating anyone with intellectual curiosity who harbours doubts.

An emblematic case was the first translations of his works in Czechoslovakia. When, in 1962, the Prague publishing house SNKLU published his collection of stories Gli zii di Sicilia (published by Einaudi first in 1958 and, then, with an additional story, in 1960), they only translated and published the stories Il Quarantotto and La zia d’America, wittingly omitting La morte di Stalin, a fierce criticism of Stalinism in the wake of Khrushchev’s revelations of the dictator’s crimes. I have no information regarding Sciascia’s reaction to this omission, but I do know how the author reacted, in 1979, when he discovered that the Bratislava publishing house Smena had omitted two stories when they published his collection of short stories Il mare colore del vino (Einaudi, 1973). They had removed La rimozione, a satire on the reaction of an Italian communist to de-Stalinisation, and Reversibilità, a politically innocuous story: “Why two?” asked Sciascia in an article that appeared in Ora in Palermo on 6 December 1979, “when they could have just removed one, namely La rimozione. Isn’t it fair to suspect that they eliminated two out of hypocrisy, so that people wouldn’t say that they had just eliminated the only story that bothered them? The other story they removed is, from that regime’s point of view, totally innocent – it talks about Sicily under the Bourbons. Just like in certain Mafia crimes, the aim is to conceal the nature, intention and purpose of that elimination”.