Dario Fo’s comedies in Japanese: interview with Kazufumi Takada

Author: Giovanni Desantis, Direktor des Italienischen Kulturinstituts in Osaka (2020-2023)

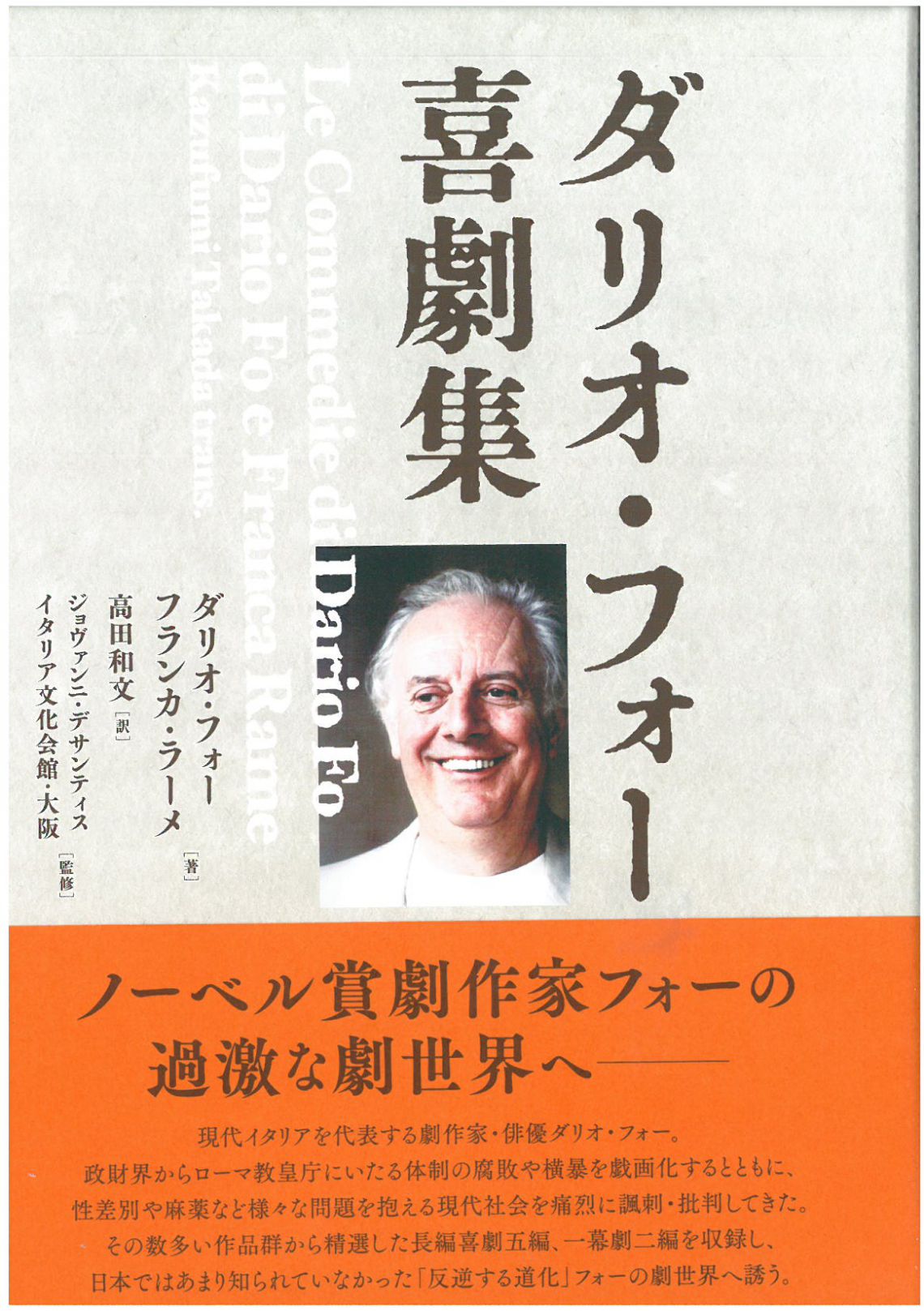

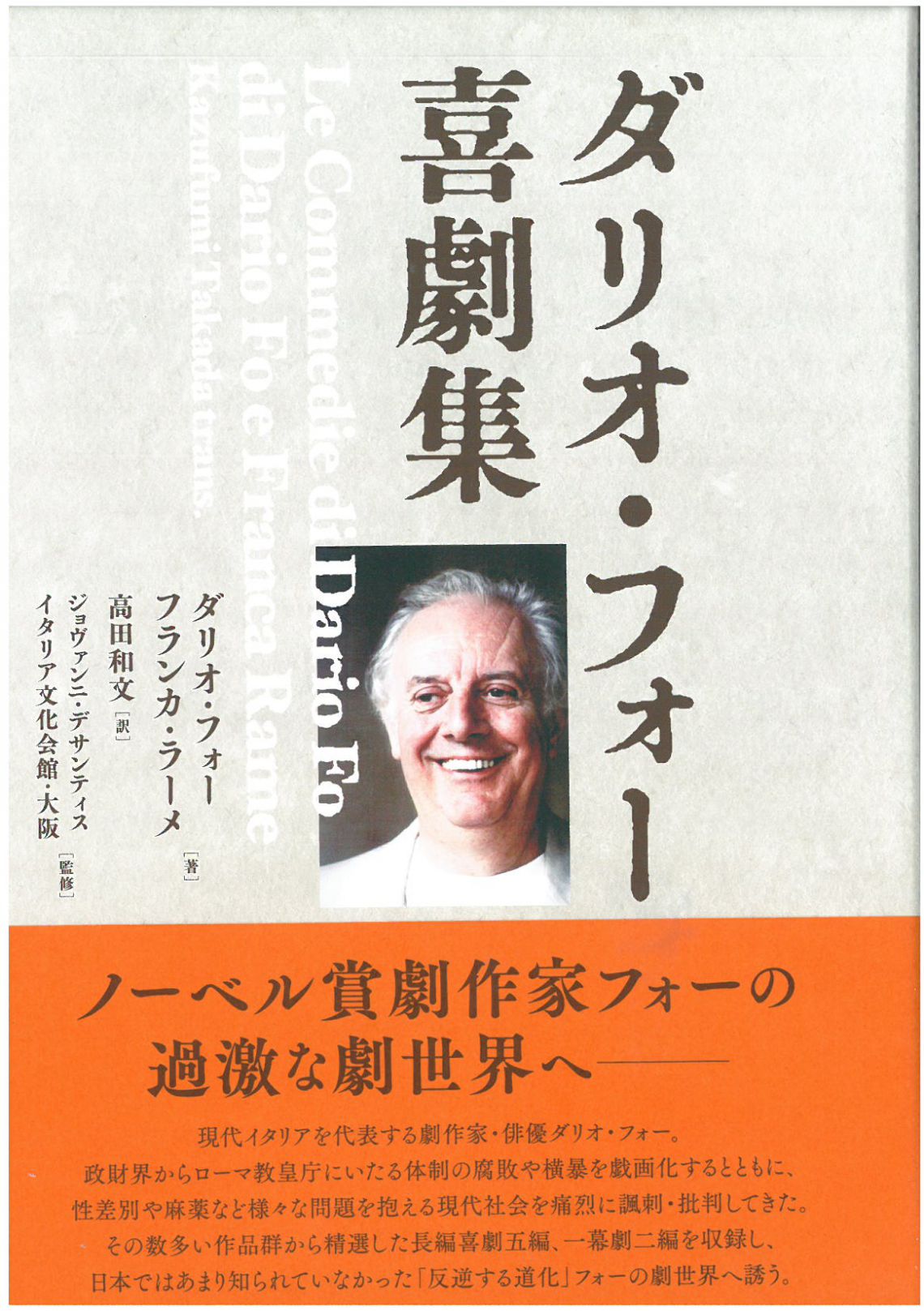

Kazufumi Takada is Professor Emeritus of the History of Italian Culture and Theatre at the Shizuoka University of Art and Culture. He was Director of the Japanese Cultural Institute in Rome. A prolific essayist, he is the leading Japanese expert on contemporary Italian theatre. He edited the Japanese translation of Dario Fo and Franca Rame’s plays: Dario Fo Kigekishuu, tr. by Kazufumi Takada, edited by Giovanni Desantis, Osaka-Kyoto, Italian Cultural Institute of Osaka – Shoraisha Publishing House, 2023, p. 448, with 21 b/w and colour illustrations.

Kazufumi, you who knew him personally: is it really important to translate Dario Fo into Japanese today?

There was a lot of attention paid to Dario Fo in Japan when he was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1997. But, in reality, his theatre was only known to specialists interested in Western theatre and to the limited audience that had been able to witness the performances on stage. Now with this translation, Fo’s works are accessible to everyone, even if only in written version. And since Fo’s theatre is very much related to contemporary life and society, it is important that it is translated into Japanese at this time, when we still have the memory of life and society of the second half of the 20th century alive.

What is it about Dario Fo that Japanese audiences might be interested in?

First of all, his comedies are basically ‘well made’ and can be enjoyed by anyone. His plays are apparently very much related to current affairs, but at the same time they make maximum use of the techniques of traditional comic theatre, which date back to ancient Roman times, through Baroque theatre, Commedia dell’arte to the popular theatre of the 19th and 20th centuries. I believe that Fo’s theatre also has a lot to do with the so-called ‘Commedia all’italiana’ of 20th century Italian cinema.

Let me give you an example: in the comedy Claxon, trombette e pernacchi, Fo imagines that Gianni Agnelli is mistaken for a FIAT worker, because the face of the FIAT President, disfigured by a terrorist attack, is mistakenly reconstructed in the operating theatre with the features of a simple worker. Here Fo uses a typical trick of comic theatre: the misunderstanding caused by the twins, which goes back to Plautus (Menaechmi), handed down to Shakespeare (The Comedy of Errors) and Goldoni (The Venetian Twins). Secondly, Fo’s comedies always deal with a very topical subject that is at the same time universal and international. One of his masterpieces, Morte accidentale di un anarchico (Accidental Death of an Anarchist), describes police bullying and the intrigues of the government and the judiciary. The play is inspired by a very specific historical event, the Piazza Fontana massacre. But Fo focuses on the attitude of the police towards Giuseppe Pinelli, who was arrested as a suspect and died after falling from the window of the Questura in Milan. This event is part of Italian history, but something similar could happen in any country in the world. The value of Fo’s theatre lies in the topicality and universality of the topics dealt with, which can be understood by audiences all over the world.

Therefore, are the corrosive political satire and criticism of contemporary society, so central to Dario Fo’s theatre, universalisable?

It is certain that his theatre is closely linked to the Italian political and socio-economic context, but many so-called industrialised countries experienced more or less the same historical path in those years. So we Japanese find very similar circumstances and episodes that also occurred in our country. And, for example, in Asia, Korea followed a similar process of economic development to Japan, and China, Thailand, Vietnam, etc. followed along this path. So, now the people in these countries can also find the political satire and criticism of contemporary society in Fo’s works relevant. In my opinion, this is precisely why Fo’s works have been translated and performed in so many languages and considered worthy of the Nobel Prize.

What historical role has Italian theatre played in Japan?

To tell the truth, Italian theatre has not had as strong an impact on Japanese theatre as that of other European countries. This is because the Japanese theatre people of the Meiji period, the era of modernisation of Japanese society and culture, tried to assimilate the techniques of modern European theatre based on realism and naturalism. As is well known, Italian theatre had its golden age in the Baroque period with the Commedia dell’arte, which was a typically anti-naturalistic form of theatre.

It is true that there was also a strand of naturalist theatre in Italy in the late 19th century, such as that of Verga and Giacosa. But in reality, the first Italian playwrights known in Japan were two great authors of anti-naturalist decadentism, D’Annunzio and Pirandello.

Until the middle of the 20th century, foreign theatre was presented to Japanese audiences almost exclusively through performances in translation, but from the 1960s onwards foreign companies began to tour directly. Thus at the end of the 1970s, the Piccolo Teatro di Milano arrived with Harlequin Servant of Two Masters directed by Giorgio Strehler. The show was a real shock for the Japanese public and critics, because it was completely different from the image of Western theatre hitherto current among them, namely realistic-naturalistic theatre. Since then, Commedia dell’arte has aroused great interest among Japanese experts and is now regarded as the most typical Italian theatre.

Dario Fo was an actor and mime before he was a playwright. How can you introduce him to the Japanese public, which traditionally has a great passion for theatre?

Unfortunately, the Japanese public can only get to know Fo as an actor through recordings of his performances. But, fortunately, today we can see many images of Fo on YouTube, so those who want to can easily access these materials.

Most of these materials are in Italian, but even without understanding the words, one can very well appreciate the richness of Fo’s gestures and visual expressions.

Today, especially after Fo’s death, there are some attempts to translate and perform his monologues, such as Mistero Buffo, but they do not seem to have had better results than those performed by Fo himself. This probably reveals that it is extremely difficult to find an actor similar to Fo who can recite such an original text.

I believe that Fo’s monologues have value as a ‘tale’ to be read or listened to, rather than as a text to be performed on stage. So they should be translated in a different way from the texts of the comedies.

Fo’s language and the translator’s tasks. A challenge?

It is clear that Fo’s language is not easy to translate. In addition to the usual difficulty of translating the text of a foreign language, there is that of translating a theatre text. That is, the translated words must be pronounced by the Japanese actors in a natural way and must be understood by the audience immediately. I believe that the audience must understand the meaning almost by intuition or feeling and not by reasoning or reflection. To translate Fo, I tried as much as possible to choose words and expressions that ordinary Japanese can understand instantly. Perhaps this was helped by the experience of having done a lot of simultaneous translation, where the interpreter has to convey the meaning immediately with the most suitable and simple expression possible.

Isn’t the special relationship, both human and professional, between Fo and his wife Franca Rame also a very interesting element?

In Italy, it is well known that Fo and Rame have always worked together in the production of plays. Abroad, on the other hand, Fo’s name has become famous for the Nobel Prize, but Franca is only considered Dario Fo’s ‘wife’. In reality, Fo’s texts were written ‘on stage’ and, therefore, Franca Rame always collaborated with Dario Fo in writing the script. In addition, Rame edited all the editions of the comedies published by Einaudi, which can be considered definitive versions. Without Franca’s help, Fo’s texts would probably have remained only as ‘scripts’ with many gaps and variations. Not only as theatre professionals, but also in their private lives, they were stronglylinked. I dined with them several times in Rome and Milan and even visited their home in Cesenatico on the Adriatic. In contrast to their attitude on stage, they were both very calm, serene, friendly and seemed an ideal couple.