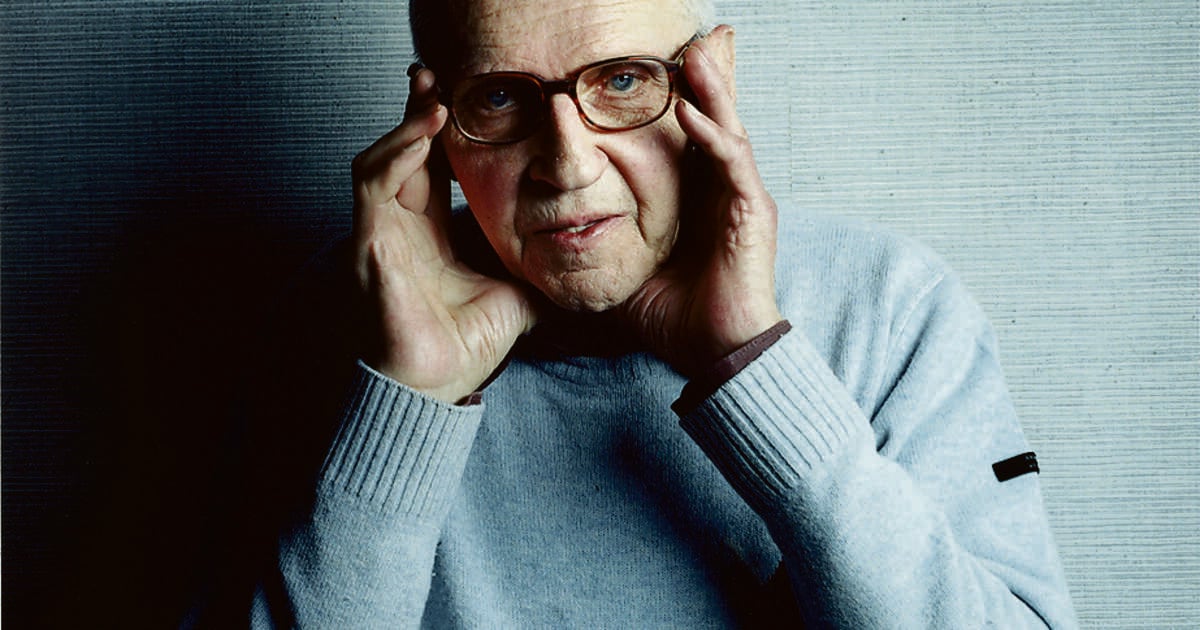

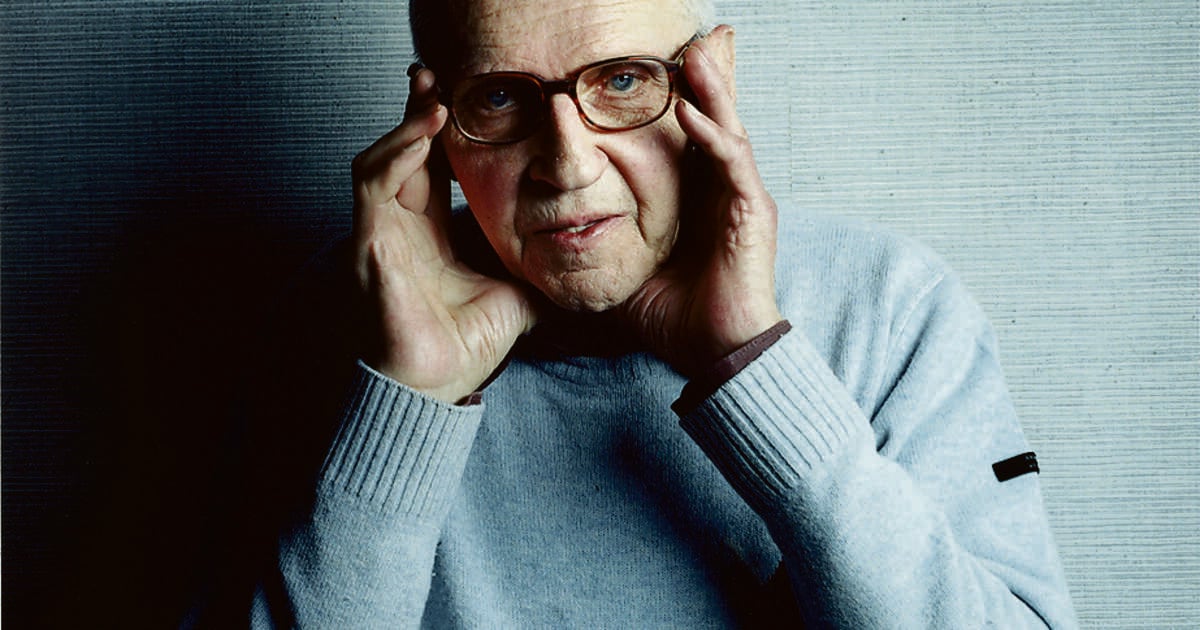

A three-dimensional passeur: François Wahl and Italian literature in France

Author: Marco De Cristofaro, Université de Mons/Université de Namur

The name François Wahl recurs with notable frequency in research on the dissemination of Italian literature in France in the second half of the twentieth century. It is enough to look at the reception across the Alps of some of Italy’s major authors to see this clearly.

Scholars of Carlo Emilio Gadda‘s work have invoked him on several occasions. Jean-Paul Manganaro recalls that the French translation of Pasticciaccio, published in 1963, was not due to the author’s fame following the Formentor Prize, but rather “to the true literary passion of an editorial director at Éditions du Seuil to whom we must […] pay tribute, namely François Wahl” (Manganaro 1994, p. 32). In line with Manganaro, Giorgio Pinotti insists on the “determination of François Wahl”, to whom we owe the “long loyalty of France to Gadda” (Pinotti 2009, p. 117).

References to Wahl are also frequent in studies dedicated to the circulation in French of another great Italian author of the twentieth century who enjoyed a long and stable success across the Alps: Italo Calvino. Laura Di Nicola attributes to Wahl the role of exceptional editor for Calvino, defining the relationship between the two intellectuals as a fruitful exchange for a broader reflection on twentieth-century culture (Di Nicola 2009, p. 130). Similarly, according to Francesca Rubini, the correspondence between Wahl and Calvino, on the occasion of the translation of Castello dei destini incrociati, subverts “the usual relationship between author-text-translator and confirms [Wahl’s] exceptional commitment not to a single title but to all the volumes published in French” (Rubini 2023, p. 101). On the other hand, Calvino himself had recalled, in different circumstances, Wahl’s crucial contribution to the translation of his works and their successful placement on the French book market (see some of Calvino’s letters in Calvino 2000, pp. 668-670 and p. 684).

But Calvino is not the only author who attributes to Wahl a leading role in the mise en forme of his work. A prime example is the publication in France of Umberto Eco‘s Opera aperta. In the introduction to the second Italian edition of the book, published by Bompiani in 1967, Eco thanks Wahl for his help, encouragement and advice regarding the French version published by Éditions du Seuil in 1965. In particular, the author emphasises how Wahl “greatly influenced the rewriting of many pages, which make the second edition partially different from the first” (Eco 2023, p. LXXIII). In the note at the beginning of the Bompiani edition, in which he recounts the history of the volume, Eco recalls that “the translation began immediately, but took three years and was redone three times, with Wahl following it line by line, or rather, for each line […] he sent a three-page letter full of questions, or I went to Paris to discuss it, and it went on like this until 1965. It was a valuable experience in many ways” (Eco 2023, p. XV).

One wonders how Wahl managed to acquire such prestige for the dissemination of Italian authors in France. Born in 1925, he obtained his agrégation in philosophy and at the end of the 1950s joined the editorial staff of Éditions du Seuil. Close to the circles of nascent structuralist theories, Wahl already showed a certain interest in Italian literature at that time.

In 1958, a few months after joining Seuil, he was entrusted with reading Quer pasticciaccio brutto di via Merulana. In an intellectual climate that was not very favourable to its publication, characterised by “cultural arrogance, prevailing Gaullism, and haughty disinterest in contemporary Italian literature” (Pinotti 2009, p. 114), Wahl was one of the few to strongly support Gadda’s work. His support for the Lombard author can be seen in all stages of the book’s publication. Firstly, Wahl insisted on the importance of the text despite the linguistic difficulty that could compromise its commercial success. Once Seuil had acquired the rights, the philosopher personally sought a reliable translator who, in his opinion, should have a certain aptitude for writing. Wahl, on the other hand, intervened personally on the text, asking the final translator, Louis Bonalumi, for revisions and clarifications.

Finally, he took it upon himself to write the preface to the volume, offering the reader a key to understanding the text and emphasising that “chez Gadda, le mot est une tentative de posséder la chose, de l’avoir ‘en personne’, comme si chaque terme était une façon d’arracher un lambeau de sa chair et ce qu’il désigne” (Benaglia 2020, p. 225).

The same interventionism can be found in the process of publishing Calvino’s works. In 1959, Seuil was reading Il barone rampante (The Baron in the Trees). Wahl was convinced of the need to publish the text, not only for its overall quality, but also for its potential public appeal. Having obtained the rights to the work, the philosopher collaborated closely on the translation. Wahl’s role was recognised by Calvino himself, who attributed part of the credit for the final version to him. As with Pastis, Wahl was responsible for the paratext of the volume, writing the back cover in collaboration with Calvino[1]. What is certain is that, thanks to the editorial director’s foresight, Seuil embarked on a determined authorial policy towards the Italian writer, whose works were published regularly in the Parisian publishing house’s catalogue.

Another emblematic case that outlines the intellectual strategy pursued by Wahl is Pietro Citati. The two had probably been in contact since 1958 (Manganaro 1994, p. 32), but it was at the end of the 1970s that Citati proved to be an author who fitted in with the editorial director’s vision. Between 1977 and 1979, Seuil read Goethe and La primavera di Cosroe, published respectively by Mondadori in 1970 and Rizzoli in 1977. In his review, Wahl describes Citati’s Goethe as unclassifiable, avoiding reducing it to the biographical genre alone and highlighting its paradoxical features, which contribute to making the volume both entertaining and erudite. However, the intelligence of the book is not enough. The main obstacle is the possible reaction of the French public who, with the exception of a small number of refined readers, are unlikely to purchase a volume of this size, six hundred pages, which is in itself uninviting. From this point of view, the depth of Goethe does not justify the considerable financial investment required for its translation, which is extremely complex from a linguistic and cultural point of view. Nevertheless, compared to what happened with other volumes, Wahl had numerous doubts about his rejection due to the extreme enjoyability of the text. Based on these doubts, however, one can understand the decision to have Seuil publish La primavera di Cosroe in 1979. In the reader’s report, the hesitation returns due to the absence of a readership in France for such a peculiar work. However, in this case, Wahl believed more firmly in the literary qualities and fascination of the book, which would attract lovers of mythology and mystery. The expanding audience required new forms of promotion, which were guaranteed by the combination of the topical theme, suggested by the setting of the novel-essay in Iran, which in those years was involved in the complex situation of the revolution, and the fascinating appeal of a primordial antiquity.

Wahl was therefore an essential point of reference for many Italian authors when it came to promoting and correctly distributing their texts in France. His involvement in the entire publishing process determined how the books were received, in some cases reinterpreting the works themselves. His extensive involvement in all aspects of the book market, his ability to influence the choices of one of the most influential French publishing houses of the twentieth century, Éditions du Seuil, and his role as a true gatekeeper of Italian literature in France, recognised by writers and scholars alike, make Wahl a three-dimensional, well-rounded passeur whose work deserves further investigation and exploration.

[1] With regard to Wahl’s involvement in the translation of Calvino’s texts, I would refer you to my article: M. De Cristofaro, Du texte au livre: François Wahl passeur de Calvino en France, in M.-H. Boblet, B. Poitrenaud-Lamesi and A.-A. Morello (eds.), Pourquoi l’Italie ? L’Italie des écrivains français, Peter Lang, Brussels, 2026.

Bibliography

Cecilia Benaglia, Engagement de la forme. Une sociolecture des œuvres de Carlo Emilio Gadda et Claude Simon, Paris, Classiques Garnier, 2020.

Italo Calvino, Lettere 1940-1985, edited by Luca Baranelli, “I Meridiani”, Milan, Mondadori, 2000.

Marco De Cristofaro, “Du texte au livre: François Wahl passeur-éditeur d’Italo Calvino en France”, in M.-H. Boblet, B. Poitrenaud-Lamesi and A.-A. Morello (eds.), Pourquoi l’Italie ? L’Italie des écrivains français, Brussels, Peter Lang, 2026.

Laura Di Nicola, “Italo Calvino negli alfabeti del mondo. Un firmamento sterminato di caratteri sovrasta i continenti, in Fondazione Arnoldo e Alberto Mondadori (ed.), Copy in Italy. Autori italiani nel mondo dal 1945 a oggi, Milan, Effigie, 2009, pp. 129-136.

Umberto Eco, “Introduzione alla II edizione”, in Idem, Opera aperta. Forma e indeterminazione nelle poetiche contemporanee, edited by Riccardo Fedriga, Milan, La Nave di Teseo, 2023, pp. LVII-LXXIII.

Jean-Paul Manganaro, “La fortuna europea di Gadda, in Andrea Silvestri (ed.), Per Gadda, Il Politecnico di Milano, Atti del Convegno e Catalogo della mostra, Milan, 12 November 1993, Milan, All’insegna del pesce d’oro, 1994, pp. 29-39.

Giorgio Pinotti, “‘Y s’sont canardés rue Merulana, au 219’ ovvero: le emigrazioni di don Ciccio Ingravallo”, in Fondazione Arnoldo e Alberto Mondadori (ed.), Copy in Italy. Italian authors in the world from 1945 to today, op. cit, pp. 113-119.

Élisabeth Roudinesco, “François Wahl (1925-2014), éditeur et philosophe”, Le Monde, 16 September 2014

Francesca Rubini, Italo Calvino nel mondo. Opere, lingue, paesi (1955-2020), Rome, Carocci, 2023.