Dante’s Inferno translated and visualized by Tom Phillips

Author: Alberto Casadei, Università di Pisa

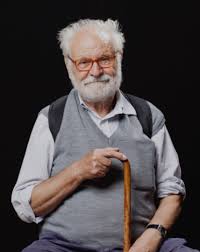

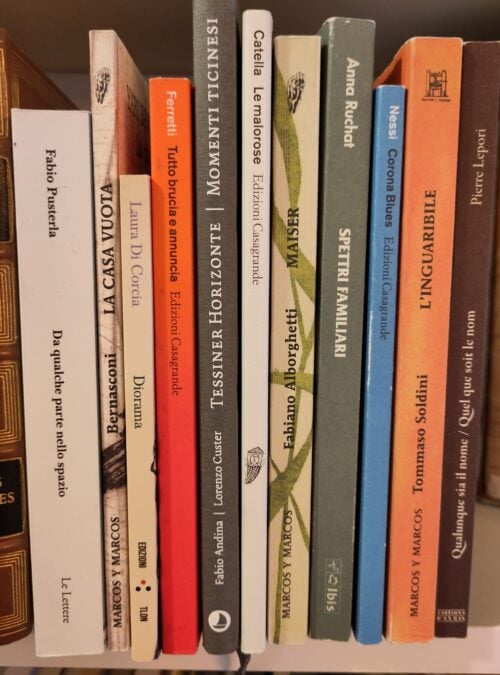

One of the most remarkable Twentieth Century English versions of Inferno is by the English artist Tom Phillips (1937). The first edition (The Divine Comedy of Dante Alighieri. Inferno. A Verse Translation by Tom Phillips with Images and Commentary) sold 180 copies and was published by Talfourd Press, London, in 1983; an affordable version, including commentary notes, of Dante’s Inferno, translated and illustrated by T. Ph., London-New York, Thames and Hudson, was published in 1985. After years of studying Dante’s work, the artist translated it and accompany it with 138 illustrations (2 introductory and 4 per canto). His translation contains detailed explanations, thanks to the Iconographical notes and commentary on the illustrations (pp. 281-311 of 1985 edition, to which further reference will be made).

Phillips belonged to the Anglo-Saxon Pop art movement when it was at its peak and his illustrations have typical postmodernism traits: the reuse of quotations from famous works, cult objects, icons of mass society etc. However, Phillips has worked on numerous artist’s books. For further information, visit his website. His reinterpretations are original and of high quality. His goal was to create a visual comment that depicted the Divine Comedy as a ‘House of Memory’, with a repertoire of recurring human characteristics. assembled in a that is adaptable to the times. His wanted to adapt his visualization to modern times. According to the well-known critic Charles S. Singleton, Everyman also plays an important part (cf. p. 283-285). Below are some examples illustrating how Phillips worked (for further information refer to Kerstin FM Blum, Im Anfang war das Wort. Tom Phillips illustrativ-poetische Dante-Rezeption, Bamberg, University of Bamberg Press, 2016; Alberto Casadei, Dante. Interpretare la “Divina Commedia” Milan, the Assayer, 2020).

The English translation is clear and flows well, due to a careful study of the critical bibliography and the relationship with the corresponding images is very significant and evocative. For example, the famous Veltro prophecy (canto I, vv. 100 ff.) is translated as follows: “until the Hound / shall come to bring her [the she wolf] down in agony. He shall not feed on land and property, / but wisdom rather, love and moral strength … “(p. 12). The mysterious hunting-savior dog can also be seen and is based on the American bus company Greyhound icon (a running greyhound: found on www.greyhound.com). The illustration clearly conveys the underlying idea (p.15). The hound is represented in four revised images, each of which indicates one of the four senses of the Scripture (but in theory also of the Divine Comedy): literal, allegorical, moral and anagogic. The text and illustrations are well integrated and are remarkably instructive.

Other combinations are much freer, for example canto V, regarding Francesca da Rimini. The translation of the famous verses with the amphora of “Amor” (100-107) is also accurate in this case, even the complex rhetorical figure “Amor, ch’a nullo amato amar perdona” (v. 103) is translated “Love that releases none, if loved, from love” (p. 44) and maintains the polytoton , although the syntax is simpler. In this episode, the relationship with the illustration is also fundamental (p. 47). It recalls the tragic destiny of Francesca and her lover Paolo Malatesta and takes inspiration from Michelangelo’s silhouettes of Adam and Eve, driven out of the Earthly Paradise, in the Sistine Chapel (the choice is well explained in the note on pp. 288 s.).

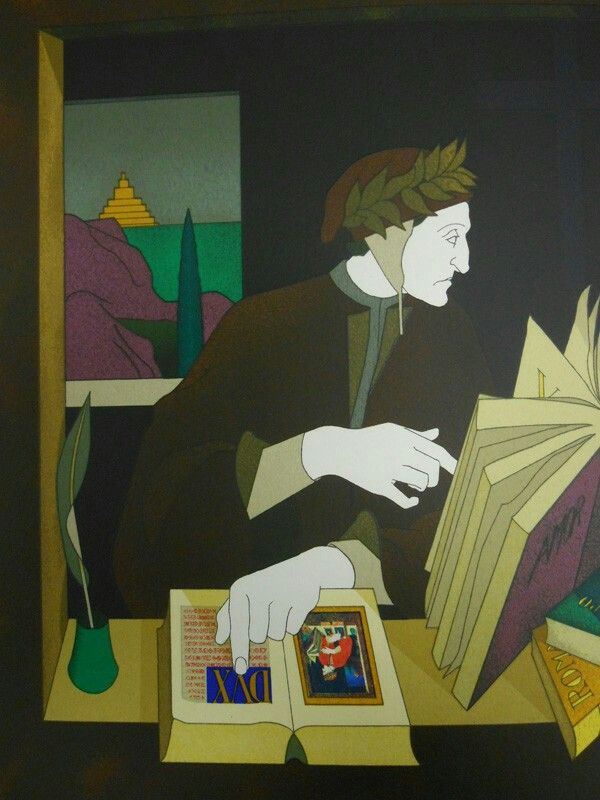

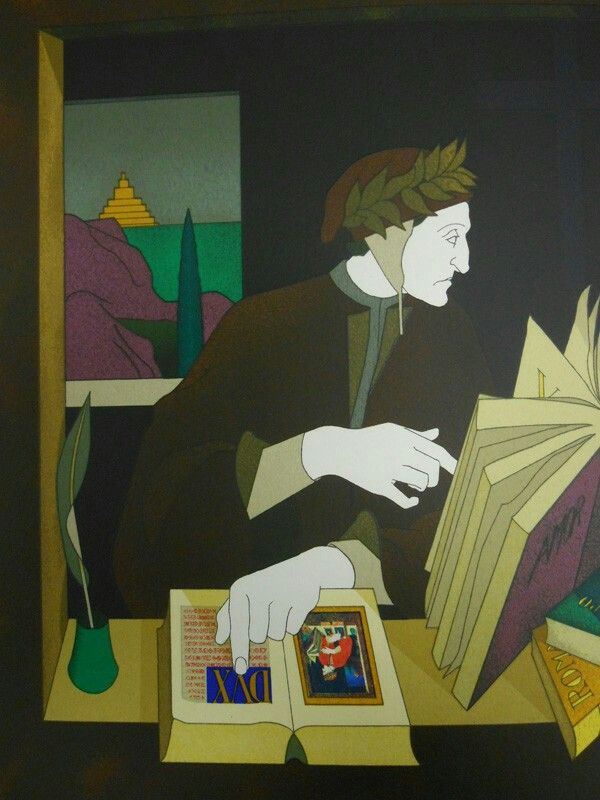

In many other cases the translation is accompanied by singular images that are, sometimes, comically grotesque: in canto XXXI, regarding the giants, on p. 253 King-Kong appears, ready to destroy New York with all its skyscrapers and the towers of an ancient city, San Gimignano, in the foreground (as specified in the note on p. 307). The reworkings of Dante’s portrait are refined (on the cover and in the counter-title page, p. 2). The pose he holds is clearly inspired by Luca Signorelli’s famous fresco in the San Brizio chapel in Orvieto (ca. 1499-1502), but is enriched with symbolic and allegorical objects.

As can be understood from these references, it is a splendid work and should be considered for the Dante celebrations in 2021. Some of Phillips’ original illustrations are kept at the Tate Modern Gallery in London. Various reproductions can be seen on his site, at the link provided.