Italian books in South Korea: the most recent trends

Author: Moonjung Park, traduttrice e docente di letteratura italiana presso la Hankuk University of Foreign Studies di Seoul

Moonjung Park teaches Italian literature at the Hankuk University of Foreign Studies in Seoul and knows the situation of Italian books in South Korea very well. In recent years, Moonjung Park explains, attention to Italian books in South Korea has grown considerably and is directed only at narrative books (Eco, Tabucchi, Ferrante etc.), but also at philosophical and scientific non-fiction, as attested by the recent translations of authors such as Giorgio Agamben, Roberto Esposito and Carlo Rovelli.

Korea, like Italy, is a peninsular country, and as such it has always been a bridge between different cultures. Its openness to the influences of foreign nations has manifested itself, in particular, in its lively interest in the literature from other countries, and its remarkable number of translations.

Before the modern era, the main points of reference for Korean culture were mainly China and Japan. In contemporary times, however, South Korea began to look westwards, particularly in the direction of the United States. For this reason, the most significant works of Western culture first came to Korea only in their English or Japanese language versions, and only later were they translated into Korean. Even the first Italian books were read in South Korea not in their original text but through versions based on previous translations into European languages, such as English, French and German. In this regard, we must keep in mind that Korean culture witnessed the widespread dissemination of English as well as, to a lesser extent, French, German and Japanese during the 20th century. Knowledge of the Italian language, on the other hand, has remained confined to narrow specialist areas.

This situation resulted in two obstacles to the dissemination of Italian books in Korea. Namely, the criterion for selecting literary works was necessarily suggested by the country of origin of the first translation, without taking into account the value judgment expressed, with respect to said works, within the Italian intellectual context. For this reason, the first Italian books to reach Korea were those that had already achieved a position of absolute prominence in Anglo-Saxon countries. For their part, the Korean publishing houses tried to come up with an independent and objective criterion – one that would also offer guarantees from an editorial point of view – for the selection of Italian texts to offer to South-Korean readers. This search led publishing houses to choose, among the most important Italian authors, those who had been awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in the 20th century. The works of these authors were then offered in anthological selections, often part of broader anthologies dedicated to world literature. This is why the first Italian authors known to Korean readers were Pirandello or Deledda: the latter, by the way, was undoubtedly valued but definitely not considered a first-class writer in Italy. This choice was also conditioned by the fact that these translated authors produced prose: a characteristic that allowed translators to measure themselves against texts that were easier to handle as opposed to the verse collections of other Nobel Prize winners, such as Carducci or Montale. Secondly, the use of an bridge language between the original text and the Korean version gave rise to translation-specific errors and, in general, to the loss of the linguistic sensitivity that is needed in order to bring the value and ‘flavour’ of Italian works into Korean.

Fortunately, starting with the new millennium, the number of Italian works translated directly into Korean has increased rapidly. This is because Korean scholars or students – who learned Italian either through university courses in Korea, or by studying in Italy – after completing their education in the Italian language, began to earnestly translate literary works directly from the original language. It may be worth mentioning that South Korea relaxed its rules on foreign travel starting from the early 1990s: since then, South Koreans can travel and move abroad more easily. As a result, many scholars have been able to improve their level of knowledge of the Italian language and culture by visiting Italy in person and spending longer periods of time to further their knowledge of the language in the Italian peninsula. The outcomes of this development were already evident at the beginning of the 2000s: in 2004, for instance, a selection of Petrarch‘s Canzoniere was translated directly from Italian, while the Korean version from the original text of Dante‘s Divine Comedy dates back to 2007.

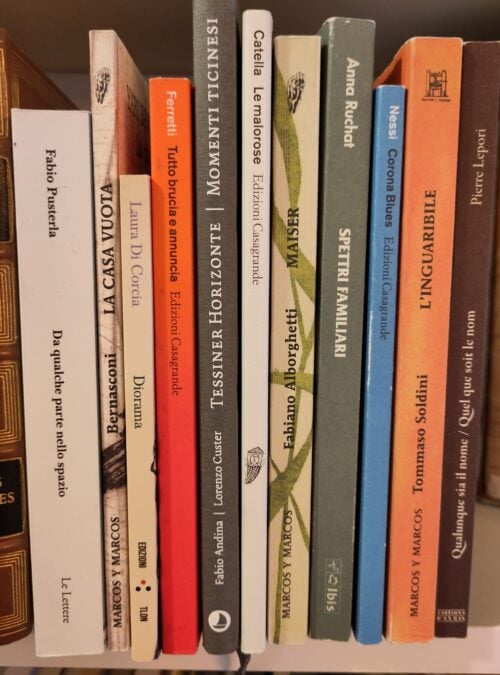

Beyond the classics, however, the Korean public’s interest has, in recent years, focused on a few authors of contemporary literature including Eco, Tabucchi, and Ferrante. This choice seems justified by the fact that the Korean culture seems to share an affinity with the themes presented by these authors, which are undoubtedly closer, for historical, philosophical and literary reasons, to those addressed by numerous writers who, over the course of the 20th century, tackled more typically Italian and European issues.

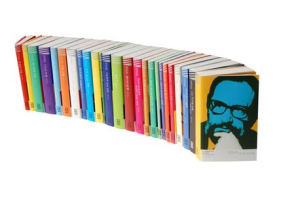

Umberto Eco is especially much loved by Korean readers, and is considered a good guide to Western culture, particularly with regard to the Middle Ages. The first novel he published, The Name of the Rose, was remarkably successful and quickly gained worldwide resonance, followed by The Pendulum of Foucault and numerous other works of fiction. Korean readers, however, have also shown considerable interest in his non-fiction production, which is linked as much to his work as a university professor as to his extraordinary capacity for making culture more accessible. Thanks to this popularity, in 2009 the Korean publishing house Openbooks published a 25-volume series entitled ‘Umberto Eco Mania Collection Set’, dedicated to a selection of Eco’s works.

As for Tabucchi, after learning of his death, an anthology collection of his works was published by the Munhak Dongne publishing house in 2013. Elena Ferrante also gained great popularity in Korea, thanks mainly to the My Brilliant Friend saga, which four volumes have all been translated into Korean. This work also inspired a theatrical adaptation, and an OTT series that is widely circulated in Korea and constitutes the new frontier of ‘storytelling’ through contemporary media.

Italian philosophical and scientific non-fiction is also translated into Korean. Among the most significant examples we find Giorgio Agamben and Roberto Esposito. As early as 2008, Agamben’s essay Homo Sacer was translated into Korean, followed by Where are we Now? – a Korean translation of L’uomo senza volto, which came out before the Italian edition – and Diritto di resistere. In 2022, Esposito‘s Immunitas and Communitas were translated into Korean, while 2016 saw the translation of four volumes by physicist Carlo Rovelli into Korean, including Seven Brief Lessons in Physics and The Order of Time, which became bestsellers among Korean readers.

In conclusion, we can say that, with these latest publications, the dissemination of Italian books in South Korea seems to have entered its third phase. From an initial period in which Italian works were translated through the mediation of Japanese or Anglo-Saxon versions, there has been a transition to a phase of direct translation from the original language, particularly with respect to literary publications, to then move to a promotion of works linked to a broader and deeper knowledge of Italian culture in the philosophical and scientific spheres.