Italian books on the history of art: some exemplary cases

Author: Davide Lacagnina (Université de Sienne)

Italian has always been the lingua franca of the history of art. It is quite rare to come across non-Italian art historians, in the past especially those specialising in the Renaissance or the Baroque, who do not know and speak Italian fluently, as can easily be imagined in this specific field of specialisation, but it is also recognition of the fact that this prestigious discipline has, historically, had one of its most important and dynamic epicentres in Italy. Perhaps, also for this reason, Italian art history books represent a small, successful enclave within the limited international circulation of Italian works of non-fiction, as the specialists in this sector are able to have direct access, without any great difficulty, to sources in the original language. This, fortunately, is now also true for scholars of Modern Italian Studies, as Italy is no longer a country to which you come merely to study art from previous centuries, as is also acknowledged by the oldest and most prestigious foreign academies present in Italy, which now focus ever greater attention on the Italian cultural production of the last few decades. The Bibliotheca Hertziana in Rome (Max-Planck-Institut für Kunstgeschichte), to offer just one of the many possible examples, has introduced a specific research initiative, Rome Contemporary, promoting studies on Italian art of the second half of the twentieth century, using Rome as a privileged point of observation. Similarly, to provide another example as regards international scientific publishing, the work being carried out by the Journal of Modern Italian Studies (Taylor & Francis, London) is direct confirmation of the growing interest in Italian culture of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, including art, which until recently was not held in high regard in the face of the dominant hegemony of a modernist model aimed at defending the primacy – geographical, chronological and linguistic – of the most accredited centres of production (and power) to the detriment of areas considered, rightly or wrongly, peripheral.

The decolonial and decultural viewpoint on which many of the current research approaches in the humanities are based has not only brought about a repositioning of Italian Studies (more generally) in the global context, but has also encouraged better equipped approaches to the ‘problematical’ memory of the country’s more recent colonial and Fascist past. These are sensitive issues, which are still quite divisive even today, and it is no coincidence that the interests of many foreign researchers working on the Italian artistic production or visual culture of the twentieth century tend to be directed towards these themes. It is during those very painful years that many of the contradictions characterising the country’s history throughout the twentieth century were concentrated and found their lifeblood. These contradictions are still at the centre of a public debate that is anything but peaceful.

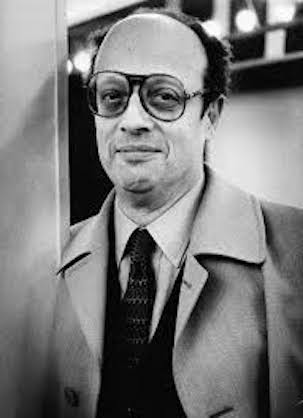

It is, therefore, useful to return to the Ventennio (the twenty-year period of Fascist rule in Italy) to begin a reflection on the presence of Italian art historiography in the international debate so as to better understand those features of continuity and discontinuity that have characterised some of the greatest achievements of this discipline internationally. One must at least start from the books published by Lionello Venturi in French or English (before they were published in Italian) during the years of his voluntary exile from Fascist Italy. The only art historian among the twelve university professors who refused to swear allegiance to the Regime in 1931, Venturi was mainly interested in European Impressionist and Post-Impressionist art and the history of art criticism, creating models that were later followed by many other art critics. Examples are his Archives de l’impressionnisme (Durand-Ruel, Paris 1939), used as a model for Gli archivi del futurismo (De Luca, Rome 1958-1962), Gli archivi del divisionismo (Officina edizioni, Rome 1969) and, lastly, the ongoing project I Nuovi archivi del futurismo (De Luca, Rome 2010-); and, also, his perhaps most famous book, History of Art Criticism (Dutton, New York 1936), translated first into French (Éditions de la connaissance, Brussels 1938) and then published in Italian, emblematically, not until 1945, following the liberation of Italy, in the collection “Giustizia e Libertà” of the Florence publisher Edizioni U. The following year Edizioni U also published Pittori moderni, which was immediately translated into English (Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York 1947), a collection of monographic studies on a number of masters of nineteenth-century European painting, from Goya to Courbet, that established a new lineage of modernity for painting and were also, in terms of their depth and methodology, an eloquent alternative to both the promotional machinery set in motion by Fascist propaganda, entrusted to the twentieth-century triumphalist rhetoric of the primacy of Italian art along the lines of its glorious Renaissance tradition, and also the grand-touriste drift of an aesthetic idealism that replaced historical criticism with the ‘sentiment’ of the formal aspect.

It was primarily his acolytes who took up and carried on the battle waged by Venturi in Italy after the war, namely to try and combine orthodox philology and its solid tradition of studies with the urgent need for a new cultural agenda, also from a methodological point of view, shielding it from ideology and attempting to bring it quickly in line with the lessons offered by European avant-garde movements and their political value. After returning to take up his chair at the University of Rome, which his father Adolfo had held, Venturi was able to influence the policies of the National Gallery of Modern Art as regards its exhibitions and purchases, during its glorious years under the direction of Palma Bucarelli, and also the research being carried out by a younger generation of scholars, first and foremost Giulio Carlo Argan. Traces of Venturi’s different approach to the old masters, his integration of the arts, design and pedagogical project for art history that was at the same time both Italian and European can all be seen in the numerous translations that were published of some of Argan’s most important works: from the monographs Fra Angelico (1955) and Botticelli (1957) to L’Europa delle capitali 1600-1700 (1964), all works published in four different editions – Italian, French, English and German – by Albert Skira, to the translations of Walter Gropius e la Bauhaus (Einaudi, Turin 1951) in German (Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1962 and Vieweg, Braunschweig 1983), Romanian (Meridiane, Bucharest 1976), French (Denoël-Gonthier, Paris 1979 and Éditions Parenthèses, Marseille 2016), Portuguese (J. Olympio, Rio de Janeiro 2005) and Spanish (Abada Editores, Madrid 2006); the translations of Progetto e destino (Il Saggiatore, Milan 1965) in French (Éditions de la Passion, Paris 1993) and Portuguese (Editora Ática, São Paulo 2000); the translations of the collection of essays by various authors, Il revival (Mazzotta, Milan 1974), in Spanish (G. Gili, Barcelona 1977); and the translations of Storia dell’arte come storia della città (Editori Riuniti, Rome 1983) in Spanish (Editorial Laia, Barcelona 1984), Portuguese (Martins Fontes, São Paulo 1992) and French (Éditions de la Passion, Paris 1995). L’arte moderna 1770-1970 (Sansoni, Florence 1970), one of Argan’s best-known works and for several decades a textbook in many university courses, was also published in various editions in Spanish (Ediciones Akal, 1991), French (Bordas, Paris 1992) and Portuguese (Companhia das Letras, São Paulo 1993).

To what has merely been a selection of his works, one should definitely add at least his important monographic works on Brunelleschi, Michelangelo and Borromini as architects, translated into various languages in a random order, partly as a result of the more general success, also in commercial tems, of the literature on the great masters of the Renaissance and the Baroque. From this viewpoint, there are numerous initiatives that can be included as regards the longue durée of the actions of the Italian publishing industry since the end of the Second World War, involving different registers and different levels of commitment: from the presentation of well-known construction sites, contexts and museums, such as the Fabbrica di San Pietro (Maurizio Calvesi) and the Uffizi Galleries (Roberto Salvini), to the most internationally famous names – Leonardo, Raphael, Bernini, etc – who, even today, remain in the collective imagination the incarnation of the Italian ‘genius’ of every age. These initiatives range from the books of the publishers Giunti Editore, intended for a broader readership, to the deft collections of the Scala Group, which, frequently, are already conceived in several languages at the planning stage, and the successful genre of ‘artist biographies’, such as those by Antonio Forcellino published by Laterza on Michelangelo (2005), Raphael (2006) and Leonardo da Vinci (2016). All three of these biographies have been translated into English (Polity, Cambridge, respectively, 2009, 2015 and 2018, and, in the case of Leonardo, also John Wiley & Sons, New York, 2018), while the books on Michelangelo and Raphael had earlier also been translated into French (Éditions du Seuil, Paris 2006 and 2008), Spanish (Alianza Editorial, Madrid 2005 and 2008) and German (Siedler, Munich 2006 and 2008).

There are several important and ambitious publishing initiatives that have been made possible by the timely recognition of the worth of Italian historiography, also on topics related to international art culture. One such example was the Anglo-Italian “Bloomsbury Collection of Modern Art” initiative in 1989, published jointly by Bloomsbury Books in London and Gruppo Editoriale Fabbri in Milan. The project was a spin-off of Fabbri’s famous “Mensili d’arte” (1967-1970), dedicated to modern European and North American art, a selection of which started to be translated into English, including Enrico Crispolti’s still important Surrealismo (1967), Renato Barilli’s I Preraffaelliti (1967) and Il simbolismo nella pittura francese dell’Ottocento (1967), and Giuliano Briganti’s Pittura fantastica e visionaria dell’Ottocento (1969). Excluded from this selection were publications that were specifically devoted to Italian art: not just those pioneeringly aimed at rediscovering the still almost unknown Italian art of the nineteenth century (outside of Italy and the ‘clique’ of specialists, naturally), for which it was feared there would be little market, but also others on twentieth-century topics, such as Maurizio Calvesi’s Il futurismo (1970), topics on which a certain international attention had, in fact, started to grow outside of purely academic circles by the end of the 1980s. Between 1988 and 1989, for example, the New York Metropolitan Museum’s important retrospective exhibition of Umberto Boccioni’s art curated by Ester Coen. The publication of the “Bloomsbury Collection of Modern Art” in Italy was also recognition of the quality of the Italian publishing industry and its market attractiveness internationally. This business operation followed the amazing success of three inexpensive collections, also published by the Gruppo Fabbri in Milan, during the happy years of the business boom in art books. “Capolavori nei secoli” (1961-1964) and “I maestri del colore” (1963-1969), both directed by Alberto Martini, a young acolyte of Roberto Longhi, and “I maestri della scultura” (1966-1969), directed by Dino Fabbri and Franco Russoli, were translated into French, English, Spanish, Portuguese, German, Dutch, Danish, Swedish, Serbo-Croatian, Greek, Turkish, Hebrew and Japanese.

On an opposite, though specular front, regarding non-fiction aimed at the reconstruction of broader contexts and moments in a history of Italian art no longer based on the protagonism of individual emerging figures, it is necessary to mention the collection “La pittura italiana” (1961-1968), directed by Roberto Longhi, perhaps the most influential and, at the same time, the most ‘untranslatable’ of Italian art historians of the twentieth century, in terms of the refined quality of his literary writing. Published in Italian, German, French, Spanish and Portuguese by Editori Riuniti in Rome and VEB Verlag der Kunst in Dresden, and distributed throughout the world by Edition Leipzig, this de facto company only published four titles, entrusted to Longhi’s closest followers, and was interrupted as a result of the high production costs, the problems encountered carrying out the photographic campaigns, delays in the delivery of texts and the peculiarities of the East German market, which offered very little for such an expensive publication.

Nevertheless, all historians acknowledge the high quality of these products, which, generally speaking, were authentic milestones in Italian criticism. Take, for example, Giuliano Briganti’s book, La maniera italiana (Editori Riuniti, Rome 1961), and the visual memory of its spectacular colour reproductions in the tableaux-vivants in Pier Paolo Pasolini’s La ricotta from the film Ro.Go.Pa.G. in 1963. All these works are still important books of reference, often anticipating lines of research that were developed internationally shortly afterwards. Moreover, the low cost of the Fabbri collections and their distribution through newsstands had the not insignificant merit of rendering accessible and affordable for everyone content of a high quality and unquestionable scientific rigour.

From a methodological viewpoint, it is necessary to highlight the translations of some of the essays in Storia dell’arte italiana (Einaudi, Turin 1978-1983), edited by Giovanni Previtali and Federico Zeri, in a collection published in 1987 in two volumes by Klaus Wagenbach in Berlin, with the eloquent title Kunst. Eine neue Sicht auf ihre Geschichte. In particular, there were the essays by Enrico Castelnuovo and Carlo Ginzburg on the centre-periphery relationship in artistic production, by Previtali on the periodisation of the history of Italian art, and by Luciano Bellosi on the representation of space, while the essays by Alessandro Conti, Bruno Toscano, Massimo Ferretti, Giovanni Romano, Salvatore Settis and Zeri represented the most advanced areas of art history research during the 1970s and 1980s. This generation of scholars was also highly considered by the publisher Gérard Monfort in Paris, which published a translation not only of Previtali’s Einaudi essay in 1997, after having already published, in 1994, a translation of his La fortuna dei primitivi da Vasari ai neoclassici (Einaudi, Turin 1989), but also, in 1993, a translation of Castelnuovo’s Il significato del ritratto pittorico nella società (another essay published by Einaudi, this time in Storia d’Italia, Vol. 5.2. I documenti, in 1973) and, in 1996, a translation of Un pittore italiano alla corte di Avignone. Matteo Giovannetti e la pittura in Provenza nel XIV secolo (Einaudi, Turin 1962). In 1993, Monfort also published Des romantiques aux impressionistes, a selection of essays from Dal romanticismo all’informale (Einaudi, Turin 1977) by Francesco Arcangeli, another of Longhi’s acolytes.

The German publishing house Wagenbach has always kept a close eye on the most important developments in Italian art historiography, as confirmed by translations of essays by Settis – from La tempesta interpretata (Einaudi, Turin 1978) to Se Venezia muore (Einaudi, Turin 2014) in, respectively, 1982 and 2015 – and the re-proposing of certain classics, such as Roberto Longhi’s Fatti di Masolino e Masaccio (Sansoni, Florence 1941) in 1992 and in a new edition in 2011. Settis’s essays have been highly appraised internationally, also as a result of this scholar’s prestigious career in both Europe and the United States. In addition to being translated into German, La tempesta interpretata has also been translated into French (Éditions de Minuit, Paris 1987) and English (Polity, Cambridge 1990). Similarly, among the most successful titles of the last two decades, Il futuro del classico (Einaudi, Turin 2004), a short, non-specialist work intended for a broad readership, has been translated into French (L. Levi, Paris 2005), German (Wagenbach, Berlin 2005), English (Polity, Cambridge 2006) and Spanish (Abada, Madrid 2006). Even an essay on cultural heritage policy, the aforementioned Se Venezia muore, sold well in its translations into French (Hazan, Paris 2015), English (New Vessel Press, New York 2016) and Spanish (Turner Libros, Madrid 2020).

In Spain, Enrico Crispolti’s Come studiare l’arte contemporanea (Donzelli, Rome 1997), published by Celeste Ediciones in Madrid in 2001, continues to be a successful long seller. It is still considered an essential, detailed support for anyone studying the history of contemporary art, finally freed of the nebulous approximation and methodological vagueness that, especially in the past, characterised how contemporary art was perceived.

This brief assessment of the cases mentioned appears to clearly indicate that, as regards the dynamics of the translation of Italian books on the history of art, the preference has, above all, been, on the one hand, for works of dissemination of a certain quality, also as a result of the bold policy to promote the Italian publishing industry in foreign markets during the 1960s, and, on the other hand, for works of methodological originality, capable that is, from Venturi to Longhi, from Previtali to Crispolti, of profoundly challenging paradigms, values and practices, on which, over the years, the discipline has periodically tended to rest complacently, out of convenience or laziness, when faced by an extraordinarily rich heritage that, now more than ever, deserves attention, clear competences and writing of the necessary stature.