Italian Literature in the Netherlands and Flanders (Belgium)

Author: Raniero Speelman, docente universitario di italiano e traduzione e traduttore letterario

Two semi-public foundations

Two semi-public foundations, the Nederlands Letterenfonds and the Vlaams Letterenfonds fund literary translations into and from Dutch in the Netherlands and Flanders (Belgium), countries which collaborate intensively in publishing and education. In these pages, we will consider translations into Dutch in 2019-2021 the three-year period. As far as Italian is concerned, the role of the Nederlands’ Letterenfonds (with 44 titles) is more relevant than that of the Antwerp institution (with only one translation). The types of the grants offered by the two institutions are also different: if in the Netherlands translations from English are by far prevalent (accounting for almost half of the approved projects, followed by German, and the three major Romance languages), in Flanders, French is the most funded language, followed by German and English. The Nederlands Letterenfonds selects applications on the basis of multiple criteria: the literary quality of the project, the translator’s curriculum vitae, the contract between publisher and translator, philological focus, and whether or not the text is particularly complex. A commission of specialists (academics or translators), with members appointed for two-year periods (and can be re-appointed only once), is in charge of awarding the grants. Within the Letterenfonds, a specific feature, Schwob, is designed to provide support to modern classics.

Translators

If we look at the translations actually published through a grant from the two Letterenfondsen, we see that many translators received grants for several titles, even within the same year. In the period under consideration, there is no shortage of translators for only one book, but translators who manage to obtain additional subsidies, such as Manon Smits (10 titles), Jan van der Haar (6 titles), Henrieke Herber (5), Pieter van der Drift (4), Pietha de Voogd, Els van der Pluijm, Mara Schepers and Mirjam Bunnik (3), outnumber the rest by far. This reveals that some translators, thanks to the Letterenfonds, manage to work more or less full-time, ensuring an overall income that is certainly not lavish, but at least decent. Among the books that have benefited from Letterfonds grants, there are many texts that are considered complex and difficult to translate and/or lengthy, such as Antonio Scurati’s books dedicated to Mussolini, Dolores Prato’s novel Nobody In The Square or Elsa Morante’s Lies And Sorcery, or works that have now risen to the role of modern classics, such as Gabriele d’Annunzio’s Il compagno dagli occhi senza cigli, a new translation of a large selection of Pirandello’s Stories For A Year, Morante’s Arturo’s Island, and a book of war reportages by Curzio Malaparte, The Volga Rises In Europe.

This does not mean that the system rejects young people. On the contrary, the Nederlands Letterenfonds collaborates with the University of Utrecht in the Expertisecentrum Literair Vertalen (ELV, Utrecht University Centre of Expertise for Literary Translation) in organising workshops and seminars for young translators, and the magazine Filter is an important point of reference for students taking the master’s degree in translation studies at the same university. But few students opt for the uncertain future of literary translation. Many publishing houses, after all, hesitate to entrust a project to someone they don’t know, and prefer tried and tested contacts. As a result, the world of literary translation remains more closed than it could be.

Quite a few translators work in tandem. In addition to the pairs mentioned above, Mieke Geuzebroek and Pietha de Voogd, Mirjam Bunnik and Mara Schepers, and sometimes Henrieke Herber and Ada Duker work together. The quality of the final product is positively affected by this collaboration.

In 2021, a version of Dante’s Inferno in free verse and in a blend between slam poetry, spoken word, and rap, intended for today’s youth, by Flemish author Lies Lavrijssen, was a literary sensation. Curiously, it was the only translation funded by the Vlaams Letterenfonds between 2019 and 2021. The work has been much criticised for the removal of the names of the prophet Mohammed and his son-in-law Ali, omitted so as not to hurt readers of the Islamic faith. If it is fair to say that the best publicity, as Marinetti knew very well, is free publicity, I do not think the book was a publishing success. Lavrijsen did not have much experience in translating from Italian, and Dante perhaps does not lend himself to street slang.

Genres and authors

Among the translated titles we find many works by contemporary authors, some well-known in Europe, including Silvia Avallone (A Friendship), Alessandro Baricco (The game), Paolo Cognetti (The Happiness of the Wolf), Donatella Di Pietrantonio (A Sister’s Story), Elena Ferrante (The Lying Life of Adults), Paolo Giordano (Things I don’t Want to Forget), Nicola Lagioia (The City of the Living), Paolo Maurensig (A Devil Comes to Town), Matteo Righetto (The Last Homeland), Sandro Veronesi (Cani d’Estate). Less recent works include Roberto Calasso (The Celestial Hunter, The Book of All Books), Fleur Jaeggy (a revised translation of Sweet Days of Discipline, The Water Statues), Giorgio Bassani (Epitaffio). Authors such as Davide Morosinotto (Red Stars, Il fiore perduto dello sciamano di K., La più grande) who, with no less than three novels, is proving to be a popular author with young audiences, and Christian Frascella with three detective stories roughly aimed at the same target audience, also make an appearance. In recent years, made-in-Italy crime novels have not been as successful as Scandinavian noirs. However, Andrea Camilleri, Giancarlo De Cataldo and Roberto Saviano are also renowned (and translated) in the Netherlands.

Translations not funded by the Letterenfondsen

Although most translations of serious works of proven literary quality go through the Letterenfondsen, there is no shortage of books published without a public grant as, in some cases, the income level of the translator is above the threshold for which grants are provided. The Letterenfondsen also compete with grants from other bodies, as in the case of Scandinavian languages for which applications are very few due to local structures (such as Norla) which offer grants for translations from Norwegian, Danish, Swedish, and Icelandic.

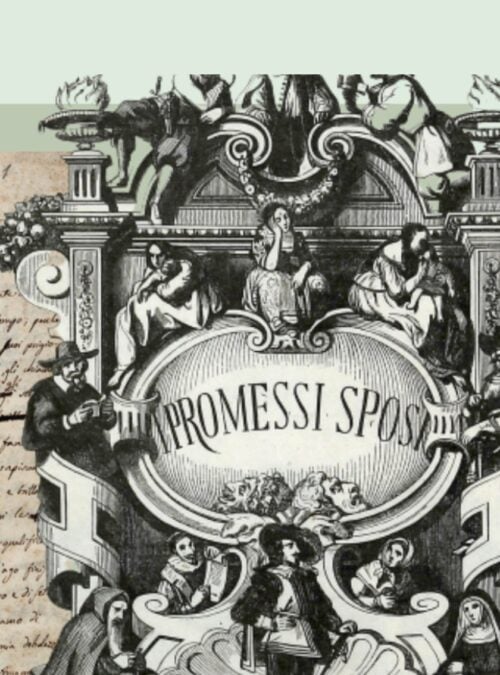

For Italian, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs offers support through the Institute of Culture in Amsterdam, which in 2021 allowed for the publication of a novel by Giorgio Montefoschi, Il corpo, translated by a group of students from the University of Utrecht, under my coordination. In addition, the edition – but not the translation – of a new version of the Divine Comedy , edited by Herman Jansen, was also funded. Another major classic is Petrarch’s Rerum Vulgarium Fragmenta translated into rhyme by Peter Verstegen, who had already won acclaim, together with Ike Cialona, with his version of Dante’s poem in tercets (2000).

Untranslated Works

A different view of translations from Italian is one that looks at books that have not been translated: an ex negativo panorama that highlights the many works that would have deserved to be translated but were instead not taken into consideration or simply missed by publishers and translators. For the sake of space, we will only mention a few writers of some success in Italy who have been around since the early 1980s.

The Netherlands has ignored several books by Giorgio Pressburger, Nel regno oscuro and Storia umana e inumana, both inspired by Dante’s Comedy. Only the earliest works by this author (and his twin brother Nicola) have been translated, while his later work has remained unknown. The same can be said about Sebastiano Vassalli, who is only known in Dutch thanks to The World’s Gold, The Chimera, The Swan and La notte del lupo, and for Roberto Pazzi, with only three books translated (Searching for the Emperor, The Princess and the Dragon and La malattia del tempo). Lastly, I would like to mention authors like Giacoma Limentani, Clara Sereni, Lia Levi, and Edith Bruck, central figures of Italian-Jewish literature, still awaiting translation. This very brief and rather incomplete overview clearly shows that it is not always criteria of literary significance that guide the ‘translation market’.

A not too rosy future: accurate picture or false alarm?

The current state of literary translation was recently the subject of a long article by Toef Jaeger, ‘Translators are the canaries in the mine’, which appeared on 8 April in the prestigious NRC-Handelsblad. Closing a series of interviews with translators and with Tiziano Perez, director of Letterenfonds, Jaeger notes that literary translations are going through a period of severe difficulties, despite a 5% increase in books sold in the Netherlands, and a total of around EUR 2 million invested in support of translation projects. A good few literary translators are changing jobs. According to the ELV, for the past ten years, fewer people have been translating and from fewer languages, with the consequence that ‘a less fertile literary landscape is emerging, in which only the most popular and best-selling products, translated from a small number of languages, are available in our language’. This phenomenon also affects English, as more and more Dutch people buy and read English books in the original version at favourable prices thanks to the Internet, Amazon’s mega-bookstores, etc. Amidst all this, Covid-19 also had its share of responsibility. At the same time, the number of reviews of literary translations in newspapers is decreasing, along with a reduction of literary journals. While in 2010 there were still 15 literary translations among the 100 best-selling books, by 2021 the number had dropped to 2 (in recent years, before Covid, there were 5 or 6).

It remains to be seen how the situation will evolve in the coming years. It is not only a question of a decline in literary translations and the number of qualified translators. We must also take into account the fact that the pay for translation work (whether funded or not) does not take into account either collective labour agreements or inflation. Even in schools, reading is in serious decline and suffers competition from channels such as Netflix, Disney and HBO, and everything which mobile phones can offer. Without a series of measures to support reading, interest in good, translated literature seems in danger. But if even the Bible is still being translated, read and studied for over two thousand years, some hope remains.