Oxymorons and quanta:

Italian books in Canada

Part Two

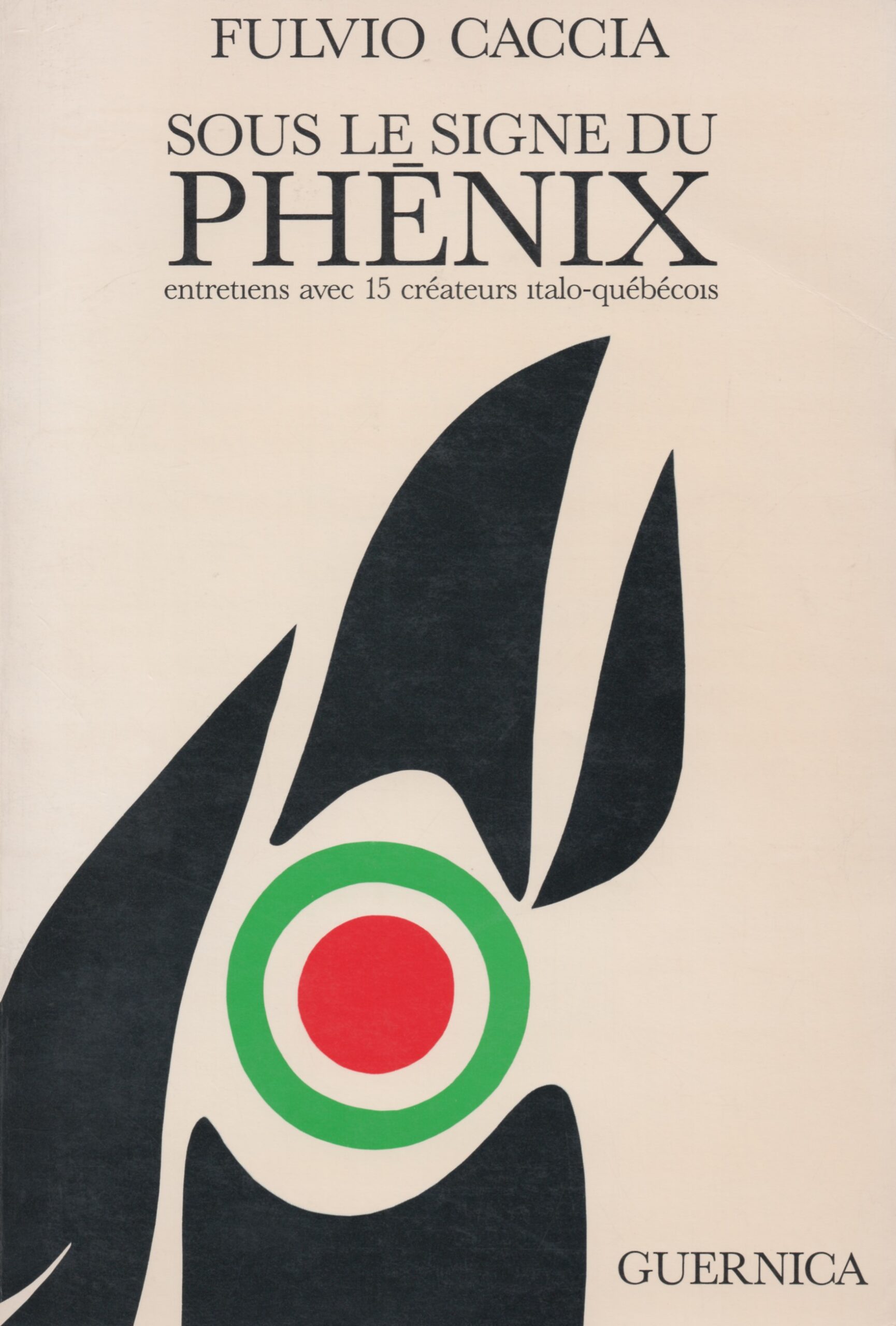

Author: Fulvio Caccia

Fulvio Caccia is both an actor in and an observer of the literary scene and its changes. Winner of the Governor General’s Literary Awards for French-language poetry, he explores the transformations of human subjectivity in both his essays and his fiction: Sous le signe du Phénix (1985), La République mêtis (Balzac éditions, 1996) and, more recently, La diversité culturelle: vers l’État-culture (Laborintus, 2017). The novels La ligne gothique, La coïncidence and Le secret explore the identity of migrants in their most intimate tragedies. And what if this were in fact one of the manifestations of love? Ti voglio bene is the title of a long poem written in French (La feuille de thé, 2023). He also runs the www.fulvio-caccia.com website.

A literature in turmoil. A century later, Canadian literature is firing on all cylinders in both French and English. Margaret Atwood was in the starting blocks. Marshall McLuhan has become the guru of the “global village”. In French, Réjean Ducharme wrote La fille de Christophe Colomb in alexandrines. The journey to Italy once again became a literary motif, both literally and figuratively. In the late 1950s, Yves Theriault, a novelist from the Far North, drew inspiration from Italy. Hubert Aquin made Renaissance Italy the backdrop for L’Antiphonaire, his most important novel. Italian writers thus became fellow travellers in another literary modernity.

The first of these was undoubtedly Italo Calvino. His novels such as Se una notte d’inverno un viaggiatore and his Lezioni americane were a hit. They intrigued a young readership keen to experiment with different forms of language. Leonardo Sciascia’s fight against organised crime and corruption caught the attention of the Canadian public at the very moment when a royal enquiry was highlighting the role of the mafia on its own soil. This led to the creation in 1972 of the National Congress of Italian-Canadians, whose mission is to defend the image and interests of the community.

But Italy also inspires dreams when its writers cross borders. Antonio Tabucchi takes us into the Indian night, close to the secrets of Pessoa. Oriana Fallaci’s hard-hitting reports and her novels are breathtaking. Trieste, a city of borders, echoes Montreal, which resembles it in its multiculturalism at the end of the world. Svevo, Magris and Daniele del Giudice would not leave the reader of this “peninsula America” indifferent.

The other heavyweight is, of course, Umberto Eco. His essays, like his fiction, propelled by the cinema, are a great success. One of his tours of Canada, worthy of a rock star, led to the publication of a book entitled Incontro with Guernica Editions when he was awarded an honorary doctorate from Laurentian University. This Canadian publishing house, founded and run for thirty-three years by Antonio D’Alfonso, will play a vital role, as much for Italian-Canadian writers who no longer write in their mother tongue as for those who still do, but who lack a publishing outlet on Canadian soil.

Native Italian writers. This is particularly true of Camillo Carli, founder of the influential Tribuna italiana, arguably the best title in the Italian press. His novel La giornata di Fabio was first published in Italy (Lalli, 1984) and then translated into French by Maurizio Binda (1991); Tonino Caticchio self-published La poesia italiana del Québec (1983); Romano Perticarini from Vancouver wrote his poems in Italian in Via Diaz, translated into English by Carlo Giacobbe in a bilingual edition (1988); Filippo Salvatore published Tufo e Gramigna (1977) before translating it under the title: Suns of the Darkness (1980); Claudio Antonelli remains faithful to the language of Dante: Scritti canadesi, partenze e ritorni di un italiano all’estero brings together nearly 200 chronicles and lectures on this theme in Montreal editions (Losna & Tron, 2002).

But the most original contribution to this contrasting landscape is undoubtedly that of Lamberto Tassinari. Director and co-founder of the magazineViceVersa, in 2009 he published the first edition of his landmark essay Shakespeare? È il nome d’arte di John Florio. This was followed by the English translation by William McCuaig (Giano 2013), and finally the French translation by Michel Vaïs, published in Paris (Le Bord de l’Eau, 2016) under the title: John Florio alias Shakespeare. In it, the Florentine-born writer authoritatively defends the thesis that Shakespeare was the son of an Italian exile of Jewish origin. It is no coincidence that a book of this kind should be published in Canada, with a not inconsiderable impact in Europe: the author proposes a novel reading of the foreign origins of all so-called ‘national’ literature. The fact that Italy and its authors, whether displaced or not, are at the heart of their advent is no coincidence either. The Association of Italian-Canadian Writers (https://aicw.ca/books/) was founded in Vancouver in 1988.

Italian-Canadian writers. Since then, the number of members of this writers’ association has multiplied, as have the anthologies that bring them together. To reflect this, the academic world has also become more structured and diversified. Joe Pivato of Athabasca University was the leader. He gave the first course on Italian-Canadian literature and published Contrasts: Comparative Essays on Italian-Canadian Writing (1985-1991).

As for English-language novels, Nino Ricci made his mark. Lives of the Saints (Cormorant Books, 1990), the first novel of a trilogy, immediately won him the Governor General’s Literary Award, Canada’s highest literary honour. In 2010, The Origin of Species (Other Press Edition, 2010) earned him the award again, making him arguably the most successful Italian-Canadian novelist of his generation.

Women writers in the spotlight. English-language writers are not to be outdone. Mary di Michele and Caterina Edwards made their presence felt in Western Canada and Toronto. In Montreal it was Mary Melfy who made a difference. The surrealism of her poetic universe, punctuated by abrupt phrasing and populated by surprising, lapidary images, reflects the inequalities of a society obsessed with progress. His theatre also reflects this. Italy revisited (Guernica, 2009), translated into French by Claude Béland (Triptyque, 2015), is a UFO between memoir and ethnographic document that has earned him well-deserved recognition.

The Italo-Quebecers. A minority within a minority, the publishing activism of French-speaking Italophones is more reserved. Marco Micone was the first to make a name for himself, and to claim it loud and clear. His plays, such as Gens du silence (1980), Addolorata (1984) and Déjà l’agonie, (1988), evoke the paradox of the son of an Italian immigrant trapped in his parents’ silence and… his trilingualism, which would normally be expected to emancipate him. Among female writers, it is Carole David, of Italian origin on her mother’s side, who stands out. She took part in the anthology Quêtes (1984), edited by yours truly and Antonio d’Alfonso, which brought together eighteen Italian-Quebec writers. She published some twenty books, including Terra vecchia (Les Herbes rouges, 2005), and Francis Catalano rediscovered his Italian roots when he took part in the same anthology. Since then, he has continued to explore his Italian roots, translating contemporary Italian poets such as Valerio Magrelli (Exfance, éditions Mains libres, 2023 translated with Antonella D’Agostino), Lives of the Saints (Bouche secrète, 2016) and Antonio Porta (Yellow, 2009), the latter published by Noroît. A poet himself, he has written his first novel, On achève parfois ses romans en Italie (L’Hexagone, 2012), in which he tells the story of a journey of initiation in Italy.

At the end of this dense and all-too-brief overview, it is appropriate to ask whether the status of Italian books in Canada has changed: are they still confined to the realm of ‘foreign literature’, or are they an adjunct to a postcolonial literature that is asserting itself? Is it the product of ultraliberal consumerism or the culmination of an emancipation embraced by a community of readers who have become transcultural? In this period of the retreat of identity, will its fertile exchange with Italian-Canadian literature survive? These questions remain open. In this respect, Canada is a textbook case. Italian books accompany the development of its culture by being both visible and invisible. It is that “quantum object”, the very metaphor of our universe in perpetual transformation and of a modernity that is seeking to detach itself from the economic liberalism that has exploited it.