The anonymous figures of libraries: Patrick Mauriès and Italian literature in France

Author: Marco De Cristofaro, Université de Mons/Université de Namur

It is now universally accepted that during the 1980s French publishing was swept by a sort of vogue (Bokobza, 2008) for Italian literature, in light of both quantitative and qualitative studies that recorded the exponential growth in France of works translated from Italian in the last two decades of the 20th century. It is significant, on the other hand, that much of the research in this area focuses on two decades marked by dates with clear symbolic significance: 1982 and 2002. Umberto Eco is almost always identified as the main reason for the renewed interest in Italian authors across the Alps. The translation of Il nome della rosa (The Name of the Rose) was significantly published in 1982 by Grasset, and its creation is often attributed to anecdotal curiosity, which, according to a classic mythopoietic device of the oral tradition of publishing, transforms chance into hagiographic predestination. Rejected on several occasions by other Parisian publishers, the text found its way to the French public through the genuine and enthusiastic enjoyment of Nicky Fasquelle, the Trieste-born wife of Jean-Claude Fasquelle, who was thus convinced to publish it, despite the negative opinion of his publishing house’s readers. This incredible story was followed by a period in which French publishers initially turned to young writers such as Tabucchi, De Carlo and Del Giudice, who made their debuts in the 1970s, before quickly falling back on works and personalities that were more reliable in terms of sales, such as crime fiction and established classics, already translated and reissued in paperback editions, such as Calvino, Sciascia and Moravia.

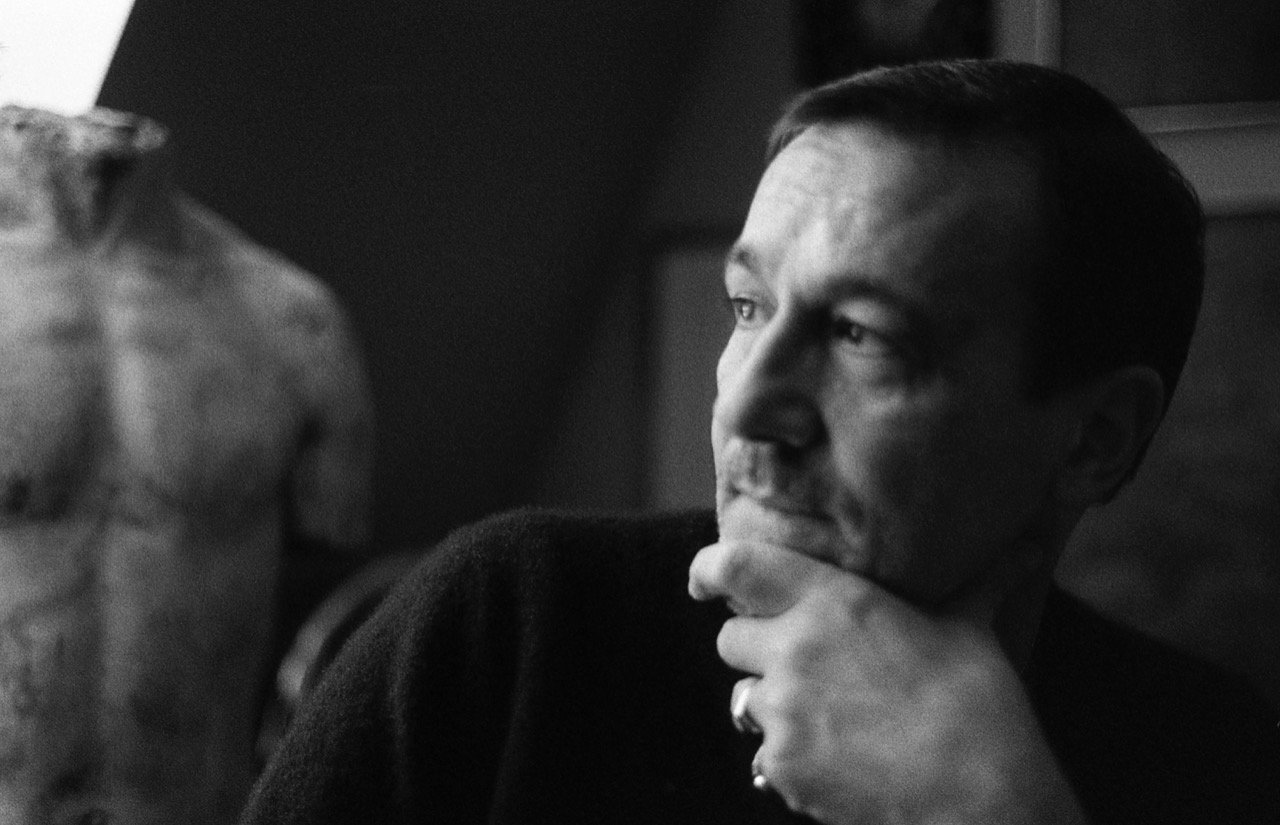

In this climate favourable to italophilie, which lasted until 2002, when Italy was invité d’honneur at the Festival du livre de Paris, Patrick Mauriès (1952-), a young and enterprising writer and publisher seeking his own space in the book market, attempted a path less aligned with the trajectory of most French publishing houses. For a biographical overview of Patrick Mauriès, see the historical catalogue of the publishing house Le Promeneur, Description raisonnée d’une jolie collection de livres. Le Promeneur. Vingt Ans d’édition (Des Cendres & Le Promeneur, 2009) and the information on the website of the Institut Mémoires de l’édition contemporaine (IMEC), which holds the Le Promeneur collection (https://collections. imec-archives.com/ark:/29414/a011449503195ShU2dz). Further information on the relationship between Patrick Mauriès and French publishing, particularly in relation to his role as a passeur of Italian literature in France, can be found in my essay Metamorfosi di paesaggi ideali: il ruolo di Patrick Mauriès e Le Promeneur nella ricezione della letteratura italiana in Francia (2021).

Having entered the book market as an author, proposing an essay on the Mannerists in the early 1980s, first to Le Seuil and then to Éditions du Regard, Mauriès was immediately confronted with the hybrid nature of publishing where the quality of writing is not enough to overcome demanding editorial filters. The volume, entitled Maniéristes, was rejected by Le Seuil on the advice of François Wahl, who, although he found it admirably written, considered it complex and difficult to read.

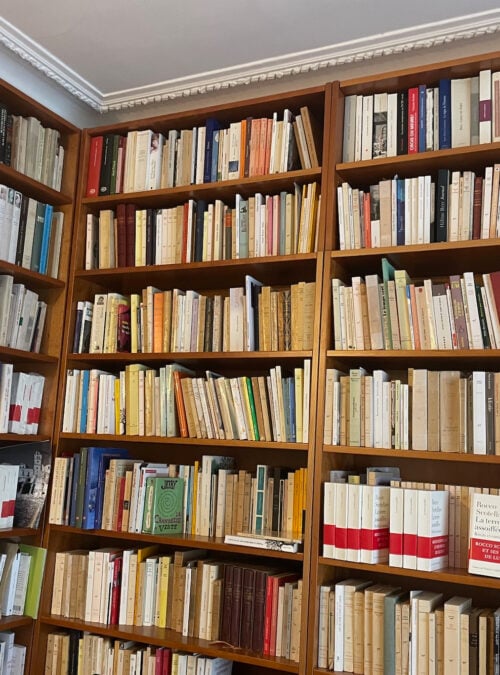

His publishing career developed in the wake of the combination of the loi du marché, abhorred at least nominally by Mauriès, who in 2009 claimed failure as a titre de gloire (Mauriès 2009), and the rediscovery of forgotten authors, les anonymes des bibliothèques (Mauriès 2009). Starting with the petite revue Le Promeneur, founded in 1981, Mauriès went on to establish his own publishing house, which at the end of the 20th century became part of the Gallimard catalogue. In the name of challenging literary canons, Mauriès turned to a specific niche of Italian literature of the 1980s, rejecting the contrast between a Renaissance, or rather Mannerist, past and the modern present in the name of an untimely approach to literature and, more generally, to artistic creation.

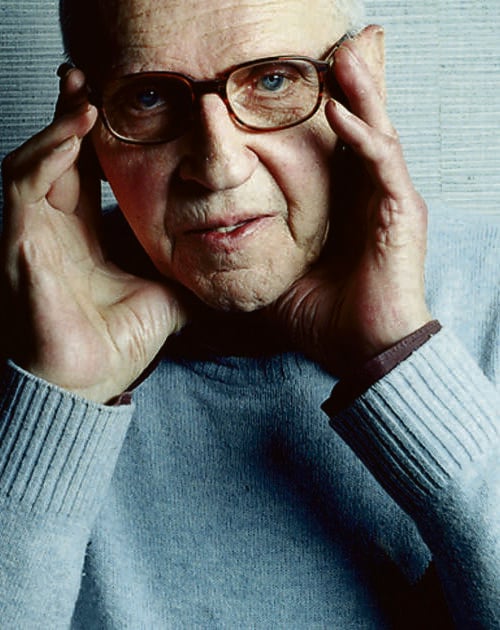

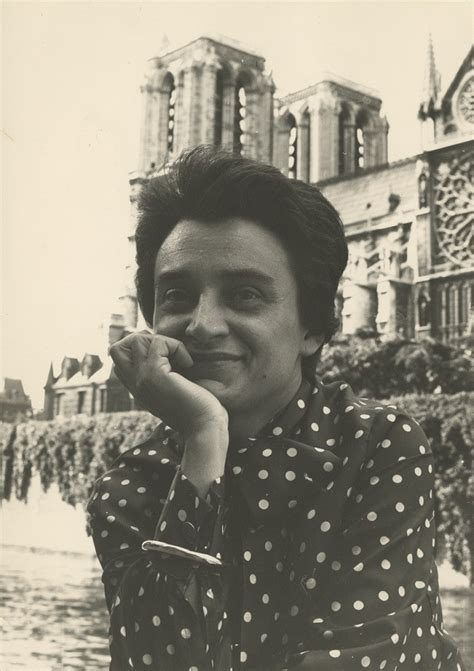

It is in this context that we must place the first articles published by the magazine Le Promeneur and devoted to Italian authors and texts. Issue 3 features Mario Praz‘s historic review of Carlo Ossola’s book, Autunno del Rinascimento (Autumn of the Renaissance), which evokes the irreversible turning point that the late 16th century represented for Italian art, and Mauriès’ own review of the impressive project of the Storia dell’arte Einaudi (Einaudi History of Art). The magazine appears to be the most immediate means of rediscovering “anonymous” figures, whom the publisher refuses to call “minor” and who are unjustly relegated to the margins of contemporary publishing. The French public thus discovers the lesser-known Gadda of Meraviglie d’Italia, of which Le Promeneur publishes Carabattole a porta Ludovica, or Arbasino‘s Pour Pasolini, or Giorgio Manganelli, who, since his appearance in the magazine in 1985, has enjoyed growing success across the Alps. Later, through the creation of a highly recognisable editorial catalogue, Mauriès succeeded in carrying out his mission of rediscovering marginal literature, broadening the perspective on 20th-century Italian literature. Giovanni Comisso and Vincenzo Consolo were the protagonists of an authorial policy that spanned almost fifteen years, during which a full identification between writers and publisher was achieved. After dedicating an entire issue of the magazine to Comisso, Le Promeneur published his Gioco d’infanzia (Child’s play) in 1989, Gli agenti segreti di Venezia (The secret agents of Venice) (1705–1797) and Al vento dell’Adriatico (In the wind of the Adriatic Sea) in 1990. More than ten years later, Gli ambasciatori veneziani (The Venetian ambassadors) (1525–1792) was published in the series of the same name by Gallimard. There was a desire to range across Italian literature, covering different historical periods and settings, without the obligation to respond to cataloguing requirements. A similar all-encompassing strategy involves Vincenzo Consolo, whose Retablo and Lunaria were published by Le Promeneur in 1988, followed by Le pietre di Pantalica (Pantalicas Stones) and La ferita dell’aprile (The wound of April) in 1990. The bond with Consolo’s regional history also shapes his narrative choices and contributes to a dialogue unbounded by time or place — in other words, an “untimely” exchange that the publisher fosters with writers from across the Peninsula. While Consolo and Comisso allow for the dual discovery of an archaic and undefined past, other Italian authors determine the aestheticising gaze of Le Promeneur. The search for textual delicacy in Palazzeschi‘s Sorelle Materassi (The Sisters Materassi) is the basis for its reissue in a new translation in 1988. What is evident is the interest in observation, the obsession with design and atmosphere, the desire to intuit, in the fleetingness of an epiphany, the broader and more complex anthropology of everyday morality. The desire to immerse oneself in the episodic gave rise to the publishing house’s other fundamental investment: Ennio Flaiano, an attentive and ruthless chronicler of everyday life, who entrusted the truest spirit of his work to the observation of the street, in fleeting moments, mostly set at night, the antechamber of a dreamlike space. The same gaze can be found in the books of Mario Praz, from Gusto neoclassico (Neoclassical taste) (1989) to Voce dietro la scena (Voice behind the scenes) (1991). The dreamlike dimension and aesthetic research that extends from the text to the graphic design of the covers and the composition of the volumes bring Mauriès closer to the vision of Franco Maria Ricci, with whom he will establish a fruitful relationship, not only professional but also personal.

This meandering path — able to embrace diverse and seemingly contrasting spatial, temporal, and aesthetic horizons — led the Le Promeneur series, upon its entry into the Gallimard group, to feature 33 Italian titles, compared with only 19 from the French literary world and 22 from English literature. It was, therefore, a very specific investment, whose unity was guaranteed by the silhouette of the motionless Promeneur engraved on the covers of the volumes and which, through the rediscovery of figures on the margins of the official canon, had finally managed to carve out its own clearly recognisable space.

Bibliography

Bokobza, Anaïs. “La vogue de la littérature italienne”. Translatio, edited by Gisèle Sapiro, CNRS Éditions, 2008, https://doi.org/10.4000/books.editionscnrs.9481

Bokobza, Anaïs. Translating Literature: From Romanticised Representations to the Dominance of a Commercial Logic: the Publication of Italian Novels in France (1982–2001), doctoral thesis, Fiesole, European University Institute, 2004

Cartal, Élodie. La réception de la littérature italienne en France des années 1980 à 2002, bachelor’s thesis, University of Grenoble, academic year 2009–2010

De Cristofaro, Marco, Metamorfosi di paesaggi ideali: il ruolo di Patrick Mauriès e Le Promeneur nella ricezione della letteratura italiana in Francia, in A. Patat & B. Poitrenaud-Lamesi (eds), Passeurs. La letteratura italiana del Secondo Novecento fuori d’Italia: ricezione e immaginario (1945-1989), Peter Lang, Bruxelles, 2021, pp. 95-115

Description raisonnée d’une jolie collection de livres. Le Promeneur, vingt ans d’édition, Gallimard, Paris, 2009

Lippolis Anna Sofia (2023). “Italian Nostalgia: National and Global Identities of the Italian Novel.” Journal of Cultural Analytics, 8(2), 1-21 [10.22148/001c.68341].