The Poets’ Publishers –

Part One

Author: Maria Teresa Carbone

© Dino Ignani

© Dino Ignani

Maria Teresa Carbone writes about publishing, literature, photography and cinema, holds journalism courses at the University of Roma Tre and for UCEAP (University of California Education Abroad Program) and is involved in literacy education. She has coordinated the editorial staff of Alfabeta2, edited the Arts section of Pagina99, and worked on the Culture section of il manifesto. Her most recent books are Che ci faccio qui? Scrittrici e scrittori nell’era della postfotografia (Italo Svevo 2022) and the poetry collection Calendiario (Aragno 2020). She has translated works by Joseph Conrad, Ngugi wa Thiong’o, Jean Baudrillard, Virginie Despentes, among others.

Almost fifty years have passed since the critic Alfonso Berardinelli compared Italian poetry in 1975 to an ‘exploded star’, a myriad of splinters flying in a thousand different directions. Half a century later, this definition remains valid according to another critic of the next generation, Gianluigi Simonetti: in his essay La letteratura circostante (Il Mulino 2018), Simonetti writes that this image ‘describes both the current situation and that of the early seventies, for which it was conceived’.

But if contemporary Italian poetry is characterised by a fragmentation that is at once chaotic and vital, what can publishers do to orient themselves and emerge in such a turbulent space? What role does the omnipresent world of the internet play? And, last but not least, is poetry still the Cinderella of publishing, as many in Italy (and the rest of the world) think, or are the days gone when, according to an old motto, ‘everyone writes poetry, but no one reads it’?

Nicola Crocetti, at least on the surface, is a pessimist. He is one of the figures who have contributed most to the diffusion of poetry in Italy, as well as being a founder of the publishing house that bears his name (in 2020 it became part of the Feltrinelli group) and, since 1988, the creator and director of the magazine Poetry. In the introduction to Dimmi un verso anima mia, the very recent ‘anthology of universal poetry’, which he edited with Davide Brullo, Crocetti writes that poetry must be ‘protected from the world’s indifference to this art form’. But there is not indifference alone, as the publisher says, albeit indirectly, when he recalls the longevity of his magazine, which ‘in 35 years of existence has published 60,000 poems by 4,000 poets in forty languages.’

The first edition of the Strega Poetry Prize, which in 2023 joins the historic award for fiction, born in the aftermath of the Second World War, in 1947, is further confirmation that in this new millennium, the oldest of literary forms gets more attention than we often think . More than a hundred publishers of all sizes sent in their texts for the first round of selection, and ‘the live streaming of the last evening, at the end of October, was the most followed event of the year on our YouTube channel with several thousand views’, says Giovanni Solimine, President of the Bellonci Foundation, which organizes the Strega Award.

‘After all’, adds Giovanni Solimine, ‘the goal was precisely this: to broaden the audience, especially young people. And I would say that we have achieved our goal, because the feedback has been very positive: in all the places where the meetings with the finalist poets have taken place, from Pordenone to Florence, from L’Aquila to Marsala, participation has been enthusiastic’.

But what do the publishers say? Can the arrival of Italy’s biggest literary prize really have a perceptible effect on the ‘niche’ of poetry? Mauro Bersani, director of the bianca Einaudi, founded in 1964 at the instigation of the Slavic scholar and poet Angelo Maria Ripellino, and long considered – along with Lo Specchio Mondadori – the most important collection of poetry in Italy, is convinced of this: according to Bersani, who presented Le campane by Silvia Bré at the Strega Poetry Prize 2023 (selected among the five finalists), ‘the effects on sales of the poets who entered the top five have been positive. Still based on a comparison with some colleagues from other publishing houses, I would say that on average, for the titles in competition of the five finalists, we saw a 50% increase in sales. Of course, the figures are not those of fiction, but it is clear that the echo of the prize has been good, useful for spreading the reading of poetry.’

This is also the opinion of Maurizio Cucchi, Mondadori’s long-time consultant for Lo Specchio, the series in which we find the names of Eugenio Montale, Andrea Zanzotto, Franco Fortini and many others, and where the winning collection of the first edition of Strega Poesia, L’amore da vecchia by Vivian Lamarque, was published: ‘It is certain that this new, prestigious prize will help to raise awareness of the authors and attract the attention of the public’, even if – Maurizio Cucchi is keen to stress – ‘the live broadcast of the award ceremony was transmitted via streaming, not television’.

A reminder for next year? Perhaps, but in the meantime, a positive evaluation of the newborn prize also includes younger publishers, whose titles did not make the cut among the five finalists. ‘In such a small and fragile market, every tessera that is used to build the mosaic is healthy’, says Agnese Manni, editorial director of the publishing house founded in Lecce in the mid-1980s by her father, while Marco Giovenale, who oversees the poetry publications of the small and experimental Ikonaliber, points out the attraction value of Strega’s organizational machine: ‘Passages on the radio, newspaper articles, interviews: it’s hard to think that all this doesn’t affect both the quantity of future publishing proposals and the attention of a wider audience than the one that normally frequents the poetry shelves.’

And if Gian Mario Villalta, publisher of two series, “Gialla” and “Gialla oro”, both born as part of the Pordenonelegge festival and produced in collaboration with Samuele Editore, sees the Strega Poesia ‘as a significant sign of commitment’, according to Maria Grazia Calandrone, who edits the collection ‘i domani’ (Turin publisher Aragno) with Andrea Cortellessa and Laura Pugno, ‘a spotlight has been put on what has always prided itself on being off the market, poetry in this case.’ And that’s not all: Maria Grazia Calandrone says she is certain that the prize ‘will help to overcome the eternal prejudice about boredom that unfortunately most of us associate with poetry, due to the useless dissection that is carried out on poetic texts in schools, instead of offering them as living matter, which concerns us.’

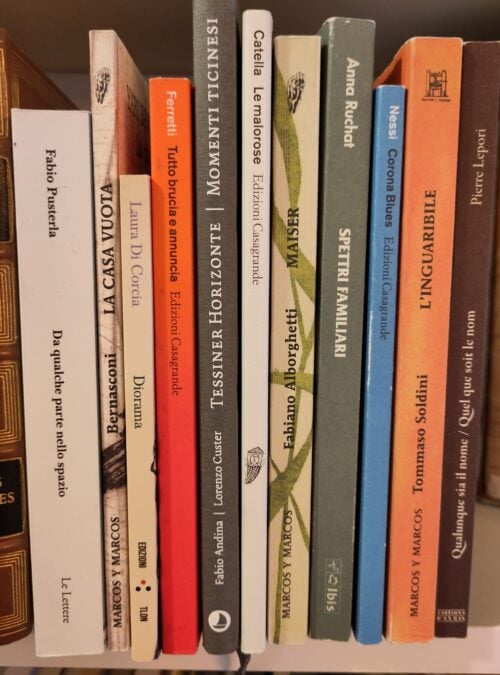

However, school can be a privileged place to encounter poetry. ‘Even today, if you have to teach a seventeen-year-old about the First and Second World Wars, take Ungaretti’s Il porto sepolto and Sereni’s Diario d’Algeria’, says Franco Buffoni, director of the LyraGiovani collection for Interlinea and a tireless seeker of new authors with Quaderni italiani di poesia, founded in the early nineties and reaching the sixteenth issue in 2023 of Marcos y Marcos editions. Cautious about the Strega effect (‘it’s too early to talk about it’), Buffoni is convinced that ‘poetry always wins out over the long run. And this is because fiction stands on three legs: the author with his personal prestige, the publisher with its power, the market which decrees the success of sales. In the case of poetry, the third foot is lacking. So, either we focus on career prizes, or we work on the younger ones, but here you have to read seriously and above all have time at your disposal and adequate critical tools.’

The position of Diego Bertelli, publisher with Raoul Bruni of the Novecento/Duemila poetry collection of the Florentine publishing house Le Lettere, is no different: ‘Fortunately, we know that it is not only through a prize that the value of a book is determined. In fact, it would be frustrating to think that more will be written and published because there are new awards. Already today, in Italy, there is no shortage of poetry on offer. In addition to quantity, there is also a lack of a certain and tangible quality. And that’s what matters.’