Goffredo Parise in other languages

Author: Giulia Pellizzato, Brown University / Università della Svizzera italiana

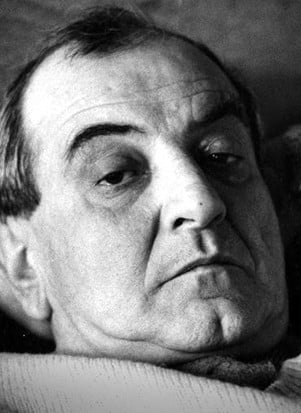

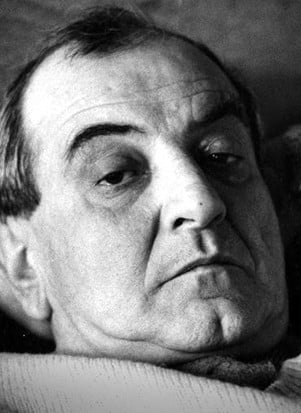

Goffredo Parise (Vicenza, 1929 – Treviso, 1986) started to make advances within the international publishing industry right from the release of his debut novel, Il ragazzo morto e le comete/The Dead Boy and the Comets (Neri Pozza, 1951). It was first translated in the United States and then taken into consideration amongst literary agents in France, England, Germany and Sweden. The first USA edition didn’t have much success with the public but a network of relations, established as a result, swiftly brought about further translations and the release of an eventual novel that was more desirable to the average reader.

In 1954 Il prete bello/Don Gastone and the Ladies (Garzanti), had great success with the public, partly due to the indignant reactions within Catholic and conservative circles. The first five reprints sold out one after the other within five months whilst English, Spanish and German translations were being prepared (1955) along with Swedish, Dutch and French editions (1956).

These versions into Western languages were mostly released by refined publishers but also some legendary ones and were always translated by prominent figures: Michel Arnaud for Gallimard in France, Stuart Hood for Knopf in the United States and Eva Alexanderson for Bonnier in Sweden. Over the next ten years there were further translations into Finnish, Serbian, Hungarian, Japanese and Slovenian, whilst his success in English was confirmed by two paperback editions, one of which was unauthorized.

His later novels Il fidanzamento (Garzanti 1956) and Amore e fervore (Garzanti 1959) were met with resistance by Italian critics but, nonetheless, were appreciated in France, Germany and Hungary and re-published over the following years.

By the time Il padrone (Feltrinelli, 1965) was released, Parise was a leading voice in Italy. The book provoked an intense debate. It overstepped current industrial literature with a powerful narrative that was both satirical and tragical and could not be reduced to political or ideological schemes. Presented by the author as a “metaphor for power”, a history of the “biological battle between the powerful and those less powerful”, the novel stimulated immediate interest on both sides of the Iron Curtain, with prompt editions in Spain (Noguer, tr. José María Valverde), France (Stock, tr. Claude Antoine Ciccione), the United States and the UK (Knopf and Cape, tr. William Weaver), Germany (Kiepenheuer & Witsch, tr. Astrid Gehlhoff-Claes), Russia (for Inostrannaja literatura, tr. Julia Dobrovolskaja), Holland (Meulenhoff, tr. J.H. Klinkert-Pötters Vos) and then in Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Sweden, Lithuania and Poland.

The tale, told in first person, is of a character who bows to become an object and the yielding property of his boss, renouncing his own desires, where to live, how to spend his time, even who to marry and whether to have children. This tale met with an audience that was particularly sensitive in countries where the wound of totalitarianism was recent (or present or near). Reprints of translations occurred, in fact, in Francoist Spain and post-Francoist, in a Germany that was divided between East and West and in Kádár’s Hungary, where the Red Army had repressed the revolution a few years earlier.

Parise’s reflections continued in his literary works, Gli Americani a Vicenza (Scheiwiller, 1966), L’assoluto naturale (Feltrinelli, 1967) and Il crematorio di Vienna (Feltrinelli, 1969), as well as reportage from the faults between the eastern and western block: Vietnam, Biafra, Laos, Yugoslavia. The former and the latter were translated with increasing attention in Hungary and Russia, where the texts appeared from time to time in volumes and magazines, whilst the publication of his previous works proceeded (The Dead Boy and the Comets, Don Gastone and the Ladies) and Parise received numerous interviews.

His extraordinary journalist labour wasn’t successful in the NATO territory, where they continued to launch his literary work published in France, Germany, Holland, Denmark, Finland and Sweden.

Sillabario 1 (Einaudi, 1972) and Sillabario 2 (Mondadori, 1982, Strega Prize) and Italy’s most famous Parisian texts spread slowly and through different routes. The first translation was released in Romania and was a combination of Sillabario 1 and the previous work, The Dead Boy and the Comets (Editura Univers, tr. Smaranda Bratu Stati). Other versions were released in Germany (tr. Christiane von Bechtolsheim and Dirk Jürgen Blask), Russian (tr. Elena Yuryevna Saprykina), English (in inverse order, first the second volume then the firstprima; tr. Isabel Quigly), French (tr. Alix Tardieu), Catalan (tr. Enric Prat), Castilian (tr. Carlos Gumpert).

On publishing the first series, Parise declared that he was aiming, through the Sillibari, at “writing things the reader would have wanted to write himself; writing things that moved men but without being too sentimental; to look closely at the facts of life and the details of these, the physical details of people, to discover, if possible, (but in friendly and tender terms, not with harshness) their character and feelings”(Altarocca, 1972, 10-11). A very delicate operation, literarily and culturally, which seems by definition to challenge the translatability into another language and another culture. To this date, even though they are included in numerous anthologies (the last was edited by Jhumpa Lahiri for Penguin Classics, 2019), the Sillibari remain an ‘unidentifiable literary object’ yet to be discovered by most of the world.

Over the course of the last ten years, Parise’s texts have become anthologised in Europe, Asia and America, whilst Don Gastone and the Ladies and The Boss remain the works for which he is most known abroad, with reprints of existing translations (even in ebook and audiobook format) and new versions in Portuguese, Croatian, Czech, modern Greek and Georgian. Thanks to the recent translation into French of Poesie (Cahiers de l’Hôtel de Galliffet, tr. Marie-José Tramuta), most of the major – and a good part of the minor – Parisian works published into volumes, are available for French speaking readers.