Antonio Tabucchi and Portugal

Author: Clelia Bettini

In Italy, more than anywhere else, many readers have come to know Portugal through the writings of Antonio Tabucchi, just as they have been able to read the poetry and prose of Fernando Pessoa thanks to the editions of Tabucchi and Maria José de Lancastre. Tabucchi’s relationship with Portugal is long and complex, with many different facets, but characterised by a genuine, mutual respect. The aim, here, is to touch on certain thematic elements, primarily because his love of Portugal is one of the most important leitmotifs of Tabucchi’s entire literary production, but also because it is now an integral part of the cultural relations between Italy and Portugal.

It was the poetry of Fernando Pessoa that first kindled the interest of a young student in love with literature for a country that, in the 1960s, was almost completely unknown to most Italians. Tabucchi came across the work of this Portuguese poet quite by chance. Immediately after finishing high school, he decided to spend a year in Paris and follow some seminars at the Sorbonne. In 1964, when he was about to return to Pisa to enrol in the Faculty of Literature, Tabucchi bought a plaquette entitled Beaureu de Tabac from a bouquiniste, where he discovered Tabacaria, one of the most original and philosophical poems of Pessoa’s heteronym, Álvaro de Campos. After arriving in Pisa, he decided that he wanted to learn the language of this poet who had so impressed him and, once more by chance, he happened to meet the professor who taught Portuguese literature at the University of Pisa, who was already one of the most important scholars of Portuguese studies in Italy. Luciana Stegagno Picchio followed him throughout his university career. The following year, together with a friend, Tabucchi drove across France and Spain in a tiny Fiat Cinquecento to discover the small country facing the Atlantic Ocean, whose language and literature he had begun studying. After this first visit, Tabucchi returned to Portugal every year, starting to spend the summer there together with his family (in the meantime, he had married the Portuguese scholar and translator Maria José de Lancastre). At the beginning of the 2000’s, his stays in Portugal became more frequent and longer, as he divided his “nomadic” life between Tuscany (Florence and Vecchiano), Paris and Lisbon.

From the very first time he spent in Portugal, Tabucchi frequented writers, poets and artists, who helped him get to know the country, its culture and, above all, its literature. Portugal, at the time, was isolated from the rest of Europe, as it was under the yoke of an oppressive dictatorship. As a reaction, the country’s contemporary artistic language had become increasingly allusive and cryptic, more than even that of the avant-garde movements of the early twentieth century, making it of even greater interest to Tabucchi. Tabucchi was a frequent visitor to Lisbon’s libraries and archives, but he also frequented many of the intellectuals and artists who stood for freedom against the oppressive fascist regime that had survived the Second World War and brutally suppressed any dissent. The poets Alexandre O’Neill and Mário Cesariny, founders of the rather late, but original Portuguese Surrealism, were two of the people he most frequented. Tabucchi wrote his graduation dissertation on this movement, which then became an anthology in Italian and was published by Einaudi in its prestigious white collection.

Even though Portugal and Portuguese culture had for some time been the focus of his studies, Tabucchi’s first narrative work was entirely Tuscan. This novel, Piazza d’Italia (Bompiani, 1975), and also his following novel, Il piccolo naviglio (Mondadori, 1978), are full of places from the author’s childhood, but transfigured and devoid of that provincial gloss typical of “local writers”. When Tabucchi began writing short stories, however, Portugal made its first appearance, refracted in multiple reflections. Il gioco del rovescio (Il Saggiatore, 1981) made him one of the most interesting narrators of his time, with its mysterious straddling of dream and reality, which remained a characteristic feature of his literature. Tabucchi knew Lisbon and Portugal very well was able to identify the hidden signs of the complex history of this old, colonial country (such as Mozambique, the setting for his short story Teatro) and this knowledge is presented in a very natural way, even for people who cannot know anything about this past, dispelling any suspicion of exoticism for its own sake. This is how Portugal, a country fascinating, but unknown, emerged in the pages of modern Italian literature at the start of the 1980s.

Two years later, Tabucchi the writer appeared for the first time on the shelves of Portugal’s bookshops. His first book, published by the famous Lisbon publishing house Vega, was naturally Il gioco del rovescio (Vega, 1983), translated by Maria José de Lancastre and Maria Emília Marques Mano, with a foreword written by one of Portugal’s most important contemporary writers, José Cardoso Pires. This foreword is perhaps one of the most enlightening texts ever written about Tabucchi’s first collection of short stories and is something that Italian readers should also be able to read, even though it was written to introduce an Italian writer not yet known in Portugal to Portuguese readers. The incipit is sufficient to understand just how struck this leading voice in Portuguese literature was by Tabucchi’s first book in Portuguese:

One reading of such a singular voice, the result of centuries of readings and journeys, is enough for this voice to remain within us.[1]

And, indeed, after this first publication, in the same collection that a translation of Calvino’s Se una notte d’inverno un viaggiatore was subsequently published, Tabucchi’s Portuguese voice not only remained, but also acquired ever greater resonance and importance in Portugal as he was able to talk about the country from a vantage point that was at the same time both external and internal.

Tabucchi’s second book published in Portugal was Donna di Porto Pim e altre storie (Selllerio, 1983), which came out just one year after it had been published in Italy. It is a collection of short stories based on a period he spent in the Azores, the Portuguese archipelago situated midway between Lisbon and the United States. The Azores are islands inhabited by fishermen and livestock farmers, famous for the passage of different species of whales as they cross the Atlantic. Whale hunting, thanks also to the valuable spermaceti, was one of the most important productive activities of some of the islands from the end of the nineteenth century to the 1980s. These islands and their whale ships are mentioned in Melville’s masterpiece and it was actually the sailors of Nantucket who introduced whale hunting to the islands. These mysterious creatures of the sea, notes on whales and the hunting of these creatures, and harpoons very similar to the one used by the proud Queequeg, but also the imagined biography of the poet Antero de Quental (1842-1891), are the basis for this completely Portuguese book, which was also something quite new for Portugal. With the exception of the reportage As ilhas desconhecidas (1926) [The Unknown Islands], by the writer and journalist Raul Brandão, and the realist novel Mau tempo no canal (1944), by the Azorian Vitorino Nemésio, this Atlantic archipelago had never been the subject of literature (it is no coincidence that the attribute chosen by Brandão to describe the islands is the adjective unknown). Donna di Porto Pim was very well received by critics and readers alike in Portugal, and Tabucchi became the most well-known contemporary Italian writer in the country of Pessoa, a poet he continued to study and translate (his collection of essays on Pessoa, Pessoana mínima, was published by Imprensa Nacional – Casa da Moeda in 1984).

In 1987, the newly-founded publishing house Quetzal, which was to become one of the leading Portuguese publishers of contemporary narrative, published another of Tabucchi’s books, Notturno indiano (Sellerio, 1984), for which Tabucchi was also awarded the Prix “Médicis Etranger” in the same year, in a certain sense, confirming the international fame of this Italian writer. In this nocturnal quête, narrated in the first person, Portugal and its complex colonial past are revealed in a way that was totally original for both Italian and Portuguese readers. The narrative ‘I’ sets off for India in search of a Portuguese friend, called Xavier, who had disappeared more than a year earlier, but ends up investigating the hidden, dark side of his own existence and the world surrounding him. Portugal’s colonial past does not emerge unblemished from this investigation, such as when, with his typical, subtle irony, Tabucchi gets his protagonist to say that the cruel governor of the Indies, Afonso de Albuquerque (1453-1515), whom he meets in a dream, seems to him very much like Ejzenštejn’s Ivan the Terrible.

The next publications in Portugal were Piccoli equivoci senza importanza (Feltrinelli, 1985), published by Difel in 1988, and Il filo dell’orizzonte (Feltrinelli, 1986) and I volatili del Beato Angelico (Sellerio, 1987), both published by Quetzal in 1989.

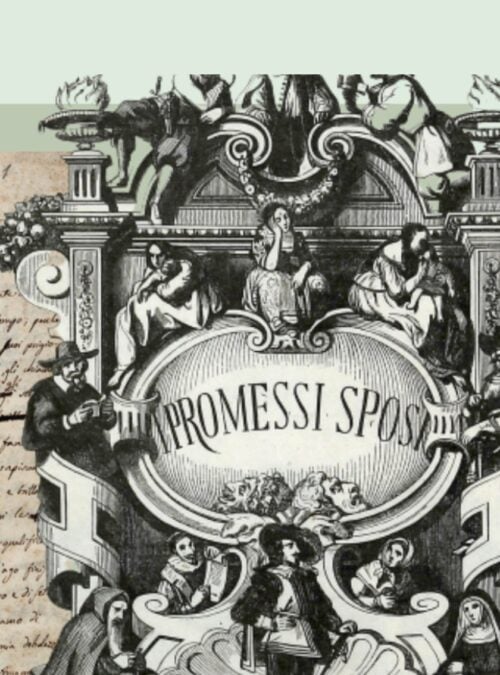

In Piccoli equivoci, Lisbon returns in the short story Anywhere out of the world, in which Tabucchi explicitly quotes Baudelaire’s homonymous poème en prose, in which the poet asked his soul: “Dis-moi, mon âme, pauvre âme refroidie, que penserais-tu d’habiter Lisbonne ? […]”.[2] In I volatili del Beato Angelico, in the short story L’amore di Don Pedro, Tabucchi takes up the macabre legend of King Peter I’s love for the Galician noblewoman Dona Inês de Castro, whose corpse was crowned, after his father had had her killed before their wedding. The sad story of the Posthumous Queen had already been admirably told from the sixteenth century, most notably by Garcia de Resende in his Cancioneiro Geral (1516) and Luís Vaz de Camões in Canto III of I Lusiadi (1572), right up to the end of the nineteenth century, then by late Romantic authors. It was Tabucchi, however, who brought the story into twentieth-century literature, making it known to Italian and other foreign readers. Portuguese Asia also appears once more in the short story Gli archivi di Macao, where the protagonist finds himself searching for documents on the symbolist poet and opium addict, Camilo Pessanha, a character who returned as a ghost in his posthumous novel Per Isabel (Feltrinelli, 2013).

From 1987 to 1989, Tabucchi was the Director of the Italian Cultural Institute in Lisbon, where he created a “Portuguese Space”, a place of encounter between Italian culture and that of the host country that was used to organise exhibitions, talks and debates, featuring numerous Italian and Portuguese intellectuals and artists.

At the beginning of the last decade of the twentieth century, Tabucchi was very much oriented towards what had become to all effects his country of adoption. In 1991, Quetzal published, with exclusive rights, his new novel, written directly in Portuguese, Requiem. Uma alucinação. As Tabucchi himself said on several occasions, Requiem was born from a dream in which his father, strangely, started talking to him in Portuguese, a language he had no knowledge of. On a hot August day, the protagonist is wandering through a deserted Lisbon to kill time before his appointment to eat with a friend after getting midday mixed up with midnight. If we look at Tabucchi’s oeuvre as one large, carefully arranged mosaic, Requiem is a key piece to understanding the whole in relation to both the themes he explores and the way he explores them, from a strictly literary point of view. It is no coincidence that this novel is written in Portuguese, nor that it is set in Lisbon and populated by a gallery of characters, both imaginary and transfigured, linked to the author’s intimate Portuguese experience.

In the same year that Requiem was published, his collection of short stories L’angelo nero was published in Italy (Feltrinelli, 1991), in which Tabucchi puts together his stories that are “sooty” like Montale’s angel, to which the title pays tribute. They include the short story Notte, mare o distanza, set in Portugal, which takes the reader back to the dark times of the dictatorship, when Tabucchi first lived in Portugal. The collection was translated and published by Quetzal the following year, as Tabucchi was by now a leading author and his books were published in Portugal as soon as they could be translated. 1993 saw the publication of Sogni di sogni (Sellerio, 1992), which contains the dream of that unique, inescapable Portuguese poet: Fernando Pessoa.

Tabucchi was by now one of the most highly acclaimed writers in Italy and abroad, but it was in 1994 that his popularity soared, with the publication of Sostiene Pereira. After that, it was impossible to think of Tabucchi without thinking of “his” Portugal. The novel was an immediate success and this success was consolidated the following year with the release of Roberto Faenza’s film. Tabucchi was closely involved in the making of the film, which contained one of Marcello Mastroianni’s last and best performances. The film, with its excellent cast of Italian and Portuguese actors and an elegant, magic Lisbon, made the Portuguese capital, its music and its light, the dream of many readers and filmgoers in Italy and the world over. In Portugal, it made Tabucchi one of the most popular and loved contemporary writers.

In 1997, La testa perduta di Damasceno Monteiro was published in Italy and Portugal at the same time (Feltrinelli and Quetzal). This novel, which is set in Porto, uses the stylistic features of a noir to tell the story of a gruesome murder that actually happened, with Tabucchi almost prophetically solving the murder of the twenty-five-year-old Portuguese man. While this is, of course, a Portuguese story, it is also a transnational story as it is a metaphor for the functioning of justice and the respect of human rights in the world, also exemplified through the gitano Manolo, an embodiment of the Roma people who have been legally persecuted throughout time in every place they have ever lived.

In the same year, Tabucchi was invited to be part of a delegation of Portuguese writers representing Portugal at the Frankfurt Book Fair, where Portugal was the theme country. This was something exceptional, as it was the first time that an author not from a Portuguese-speaking country had ever been considered a Portuguese author, highlighting the high esteem in which the Italian author was held as well as his popularity.

From the end of the 1990s, Tabucchi started to spend more and more time in Portugal and, in 2004, he was granted Portuguese citizenship for cultural merits. These were the years in which Tabucchi was most active politically, above all in Italy and France, but also in Portugal and Spain. His analyses were published by the leading Italian, French, Spanish and, obviously, Portuguese daily newspapers, but it was often his more “peripheral” vantage point from Lisbon that enabled him to achieve the necessary distance to write about what was happening elsewhere. At the beginning of the 2000’s, Tabucchi swapped editors in Portugal, leaving Quetzal for D. Quixote, a publishing house that contained some of the most important contemporary writers from all over the world in its catalogue. In addition to all his new works, he gradually republished all his previous works with his new publishing house.

Portugal remained a constant presence in what was to be his final period of literary production, but, as already mentioned, always within a constellation of his most diverse personal and cultural experiences. Take the echoes of Sephardic Portugal in Yo me enamoré del aire, containing short stories from his final collection of unpublished short stories, Il tempo invecchia in fretta (Feltrinelli, 2009), or his Portuguese stories in Viaggi e altri viaggi (Feltrinelli, 2010), both published posthumously in Portugal (respectively, April 2012 and 2013). When he died in Lisbon, on 25 March, the Mayor of Lisbon arranged for his body to lie in state in the main room of the Biblioteca do Palácio Galveias to pay tribute to the “most Italian of Portuguese writers” and Tabucchi’s ashes were placed in the Escritores portugueses (Portuguese Writers) section of the Cemitério dos Prazeres, the same section of the cemetery where the protagonist of Requiem spoke to the Old Gypsy Woman and to the ghost of his friend Tadeus, suspended between past and present, dream and reality.

[1] A. Tabucchi, O jogo do reverso, prefácio de José Cardoso Pires, Lisbon, Vega, 1983, p. 7.

[2] A.Tabucchi, Opere, edited by Paolo Mauri and Thea Rimini, Milan, Mondadori 2019, vol. I, p. 689.