Echoes of Trieste in the French publishing world (first part).

Author: Laurent Feneyrou (CNRS)

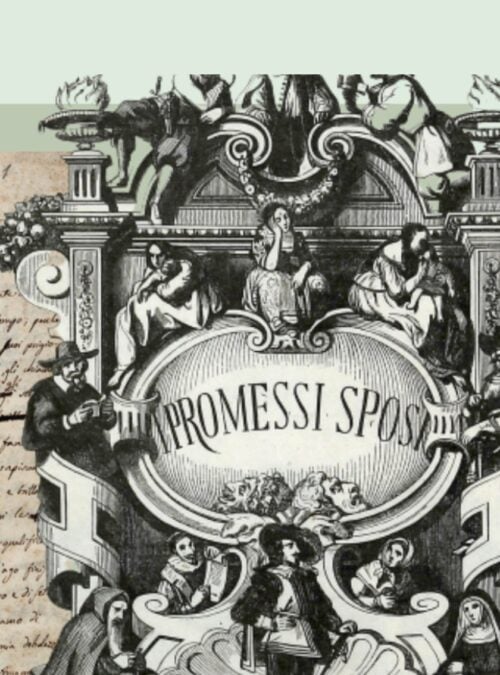

In 1917, one of the first French translations of a work by an author from Trieste, published in Switzerland and ingeniously signed Tergestinus, was Irredentismo adriatico (L’Irrédentisme adriatique), in which the socialist journalist and essayist Angelo Vivante paid great attention to the compromise and the defence of Balkan autonomy, as well as the interests of both coastlines, Italian and Slav. Six years after the suicide of Vivante, whose “almost a-national” tendencies meant he was unable to accept the demise of his utopia, Benjamin Crémieux translated Scipio Slataper’s masterpiece, Il mio Carso, with the title Mon frère, le Carso (1921), which was republished in the same year. The book had been received with a certain indifference when it was published in 1912 by Libreria della Voce. The author, a pioneer, captured the drama of a generation born during the final decades of the nineteenth century – a generation destined to be sacrificed on the First World War’s battlefields, on Mount Podgora in 1915 in the case of Slataper. He shared the tensions and contradictions that characterised his native city and, one might say, also divided it: its values and torments; a certain marginality as regards the rest of Italy; and its synthesis of the blue reflections of the Adriatic and the white rock of the Karst plateau, the calcareous plateau extending from the foot of the Julian Alps.

So how can you define the literature of Trieste, if not with this composite nature, this “border identity”, as Angelo Ara and Claudio Magris later called it? All the more so as, despite Italo Svevo’s first novels, this literature emerges in exile, in Florence in 1909, in the writings of Slataper in the pages of La Voce, and then with the splendid Piccolo canzoniere in dialetto triestino by Virgilio Giotti – those pici e tristi (small and sad) verses, but also full of love – published in Tuscany in 1914 by Ferrante Gonnelli. Should we limit ourselves to just writers from the city or also include, more broadly, those of the region? But to where exactly? To its former borders? And where does Italy end? At the River Isonzo? Trieste? Beyond? In that period of competing claims, national criteria and geographical and military considerations were all jumbled together. Is being a native of Trieste a necessary prerequisite to claim that one belongs to the literature of Trieste? Is there just one literature, a literature of triestinità intentionally rendered extraneous to history? And this literature is only the work of those who express themselves in Italian or dialect? What do we do then with the exceptional verses in Slovene of Srečko Kosovel, which, too, were composed on the Karst plateau, or the novels, also in Slovene, of Boris Pahor and Alojz Rebula? And which dialect? The triestino of Virgilio Giotti, Claudio Grisancich and Manlio Malabotta, the gradese of Biagio Marin or the rovignese of Ligio Zanini? These dialects are not at all vernacular, but adaptable, both archaic and modern, capable of uniting everyday life and verse. And these dialects are not, as Pier Paolo Pasolini would later insist, secondary or ancillary languages, but absolute languages, occasionally corrected to satisfy the needs of literature. Poetry does not pass from a major language to a minor one, to the particular details of a region, city or quarter, or worse still to a mythical essence of itself, and not even to just a word, full of Venetian, Slovene, Croatian and Austro-German echoes, in addition to Greekisms and Latinisms. Does not every poem make us listen to a foreign language?

That which the writers Ferruccio Fölkel and Carolus L. Cergoly will later call, in Austro-German, the Katastrophe, rendered inescapable by the First World War, had already led to the disintegration of the Empire: “The agony of the Habsburgs was long. The end appears rapid. The yellow and black standard with the double-headed eagle, emblem of the ruling house, was torn down. Hurrah. Boo. 1382-1918.” Trieste, now orphaned, without its industries, deprived of its hinterland, of the markets of Carnia and its more distant former territories, dies young together with Franz Joseph. Or, rather, Trieste was unable to die. The psychiatrist Franco Basaglia, much later, would say: in order to be reborn, Trieste must first die, but it refuses to.

While fascism was already reigning in Italy, France discovered Ettore Schmitz, alias Italo Svevo, thanks to Paul-Henri Michel, who translated La coscienza di Zeno (Zéno, 1927) and Senilità (Sénilité, 1930). It was necessary to wait until the 1960s, however, before it was possible to read in French his short stories and until 1973 to read Una vita and his autobiographical writings. Subsequently, thanks to the tireless work of Mario Fusco, his three great novels were finally translated in a more consummate way. Like Zeno, who was unable to choose and was a master of evasion and indecision so as to leave open possibilities, Svevo traded in Austro-German, but wrote secretly in Italian, and some of his characters, the last representatives of the Ostjudentum, evoke the crazy meshuge. An expert in the meanderings of the soul, an ironic and tragic poet, lucid and yet masked, of a subject now in its twilight, of the malaise of civilisation and the crisis of the bourgeoisie, Svevo had taught James Joyce one aspect of his city, that of the anguish that preludes renunciation, dissolution, life “as a compromise to the point of self-destruction”.

After 1930, there was a long silence. The tragedies leading up to the Second World War and those that took place during the war followed one after the other: the promulgation of the Racial Laws on 18 September 1938 by Benito Mussolini in Piazza Unità d’Italia, before a festive crowd in a city that hosted the third largest and most influential Jewish community in the country; the Risiera di San Sabba, the only Nazi extermination camp in the Mediterranean, where Jews, partisans and political opponents, both Italian and Slav, died in gas chambers, in a hail of bullets, from the torture they suffered or with their necks broken with a heavy metal sledgehammer; the foibe, natural sinkholes in the Karst plateau, where thousands of people were murdered by the fascists, but also during the operations organised by Marshal Tito to spread terror among the Italian populations in Julian March and Istria, in addition to eliminating his political opponents in Yugoslavia. Because the war did not finish in 1945 in Trieste. The dividing up of its “Free Territory”, created by the Treaty of Paris in 1947, placed the city, until 1954, under the control of the British and Americans, who carefully observed the other side of the Iron Curtain, just a short distance from Trieste.