Italian books in Brazil

Part Two

Author: Patricia Peterle, Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina

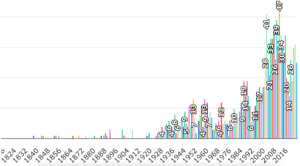

In order to gain a clearer idea of the presence of Italian books in Brazil, it makes sense to look at the following graph, which confirms a considerable and continuous increase in these flows from a chronological point of view:

The source of this graph is the Dicionário Bibliográfico da Literatura Italiana Traduzida no Brasil, an online project launched in 2010, the aim of which is to map all works of Italian literature translated in Brazil. While the project aims to stimulate and facilitate research into Italian literature in translation, bringing all this data together on a single platform also provides a better understanding of the dynamics at work. The efforts of all the professors and researchers involved are aimed precisely at bringing together all the scattered information in order to transform it into sensitive, systematised data. This project, coordinated by the Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina in collaboration with other Brazilian universities, is undoubtedly a very important resource for anyone with an interest (or even a simple curiosity) in studying the presence of Italian literature in the Brazilian publishing world.

As the graph shows, interest in Italian books is continuous and constantly increasing. While in 1901 there were three translations, two of which were of Silvio Pellico (again, Le mie prigioni) and one of Gabriele d’Annunzio’s novels, Il fuoco , over a century later, in 2011, there were more than forty-seven translations in a single year, covering a very wide range of literary genres and publishing choices. Indeed, they range from Emilio Salgari to Giorgio Caproni, from Dante (always reproposed) to Roberto Saviano, from Italo Calvino to Niccolò Ammaniti, from Andrea Camilleri to Alessandro Baricco, from Luigi Pirandello to Edmondo De Amicis, from Elio Vittorini to Gianni Rodari, to name just a few names on a list that is beginning to grow and diversify.

If we go back to the graph and look at it more closely, we can see that between the 1930s and 1940s there was no real growth, but rather a steady increase in the number of works translated, which then rose sharply in the following decade. This observation has only been possible thanks to the processing and systematisation of data from the Dicionário.

What else can we say about these years? We certainly need to look deeper into the context of reception, because the history of translation is not, as we know, isolated from the concomitance of multiple political and cultural tensions. In fact, this is a very special period in Brazilian history. For fifteen consecutive years between 1930 and 1945, Brazil was ruled by Getúlio Vargas, who implemented a veritable “nationalisation campaign” during what was later known as the Estado Novo. The aim of this campaign was to strengthen Brazilian culture and patriotism, and many initiatives were launched to this end. With regard to the use of foreign languages in particular, it is worth recalling the ban on teaching them and the adoption in 1939 (at the same time as the racial laws in Italy) of even more drastic measures, such as banning their use in public. In 1942, with Brazil’s entry into the war, repression became even more violent, to the point where those who did not speak Portuguese risked imprisonment. The very memory of immigrants was threatened and undermined. So it was no coincidence that it was in this atmosphere of the early 1930s that a work like Giovanni Pascoli’s Inno a Roma appeared. It was written in Latin and first published in 1911 as part of the national competition organised to celebrate the founding of Rome (on occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Kingdom of Italy). This was, until recently, Pascoli’s first and only text to be translated in Brazil, as it was only in 2015 that another of his works, Il fanciullino, was translated. It may seem strange, but the translations are part of a wider cultural history, which is bound to influence the editorial choices themselves. The exaltation of the historical and mythological figure at the heart of Pascoli’s hexameters was the catalyst that caught the eye of translator Aloysio de Castro, professor of medicine, poet and director of the Instituto Ítalo-Brasileiro de Alta Cultura, who in 1935 reaffirmed the glory of Rome and hoped for “the complete victory of Italy and the consequent victory of civilisation”. In short, the Brazilian reader’s first contact with Pascoli’s texts is necessarily patchy and marked by those inevitable inflections that the weight of the cultural context entails.

Giuseppe Ungaretti arrived in Brazil in the mid-1930s to take up the first chair in Italian studies at the University of São Paulo. From 1937 to 1942, Ungaretti devoted himself to teaching Italian literature, revisiting traditional authors, such as Iacopone da Todi, Petrarch, Dante, Leopardi and Vico, from a foreign and unfamiliar perspective. At the same time, he better defined the themes that would mark his poetry: innocence, memory and absence. On his return to Italy, Ungaretti did a great deal to popularise Brazilian poetry, writing prefaces to various translations, such as Siciliana by Murilo Mendes. It is worth noting, however, that Brazilian translations of Ungaretti’s poems in volume form arrived very late, only in the 2000s. Amazement and bewilderment are perhaps the two words that might describe Ungaretti’s experience in Brazil, feelings that can be read in the lines of Monologhetto, included in the collection Un Grido e altri paesaggi (1952), where the poet recalls his arrival in Recife, on board the ship Neptunia that had left the port of Genoa. In the mid-1940s, after Vargas and at a time of greater freedom, Ruggero Jacobbi arrived in Brazil as director of Diana Torrieri’s theatre company. Jacobbi was to become a fundamental figure in the history of Brazilian theatre, where he remained until 1960. On his return, he did not abandon the experience of those fourteen years that had left such an indelible mark on him; not only did he undertake the translation of various poets, but he also taught Brazilian literature at the University of Rome.

Between the Vargas dictatorship and the military dictatorship (1964 and 1985), a group of poets stirred up the cultural scene. These were years of great effervescence, with the foundation of the Museu de Arte de São Paulo (to which Pietro Maria Bardi and Lina Bo Bardi contributed), which dates back to the late 1940s, and the construction of Brasilia, the “capital of the future” inaugurated in 1960 by Juscelino Kubitschek (with the slogan 50 years in 5), to mention just two events of different but equally relevant scope. The noigandres group, made up of Haroldo de Campos, Augusto de Campos and Décio Pignatari, was organised around the journal of the same name, whose programme aimed to bring about a profound renewal of literary and artistic language. The term noigandres, cited by Pound in his Cantos and taken from a text by Arnaut Daniel, was used by the Brazilian group to designate poetry on the move, experimentation, a new way of conceiving poetic values, in line with a rediscovery and reinterpretation of tradition (Cavalcanti, the Dante of the Petrose Rime, Hopkins, Joyce, Pound). Umberto Eco has described Haroldo de Campos as the greatest contemporary translator. Indeed, his translations of Dante (Rime Petrose and Cantos I, II, XIV, XXIII, XXI, XXXIII from Paradiso) and other poets of the Dolce Stil Novo are worthy of note. They are also cited in the famous and diverse Manifestos published by the same group. It has to be said that, in the case of Haroldo de Campos, contact with Dante’s work influenced his own poetic production, to the extent that the author of La Commedia became one of his true companions in literary creation. This relationship with Dante influenced both his formal research, expressed, for example, in the use of terza rima in a work like A máquina do mundo, and his adoption of the theme of the journey, as in Signantia quasi coelum, which takes us from paradise to hell. But the poetic and intellectual galaxy of Haroldo de Campos, one of the greatest representatives of Brazil’s second 20th century, highlights the way in which the practice of translation and reflection on it can nourish, above all, creative practice and personal writing. Referring back to certain ideas of the Brazilian writers of the 1920s, to Oswald de Andrade’s anthropophagy in primis, his proposal is that of a “transcreation”, that is to say, of a critical and translational operation whose aim is to be as faithful as possible to the invention, and not to the literal meaning, even if it means crossing the limits of a historicist vision. And it is precisely from this “anachronistic” perspective that Campos saw Leopardi as a theoretician of the avant-garde, read Dante’s Paradise in dialogue with Mallarmé, and took up the texts of the Dolce Stil Novo in a highly original way, particularly one of Cavalcanti’s most famous songs.

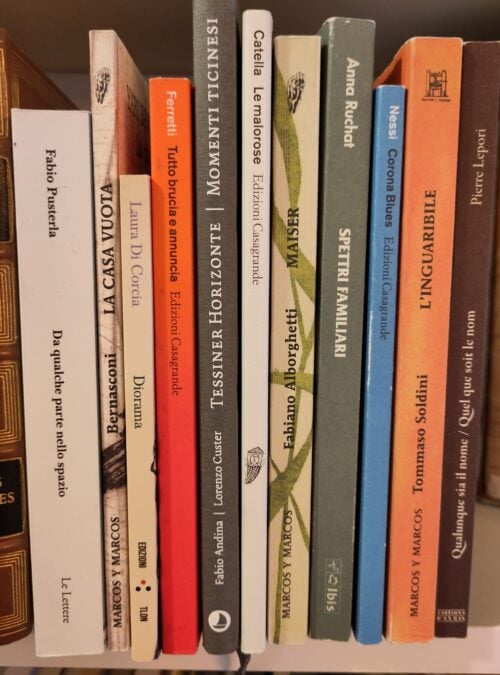

What we can see in the history of Italian books in Brazil, then, is the existence of a dense network of dialogues and intersections. Certain authors obviously enjoy special attention, as in the case of Umberto Eco and Italo Calvino, whose novels and essays have almost all been translated. But as we know, this is not an exclusively Brazilian phenomenon. Others, on the other hand, such as Cesare Pavese and Leonardo Sciascia, attracted a great deal of interest in the 1980s. In the case of Pavese, we can also say that there was a new wave of interest from publishing houses on the occasion of the 70th anniversary of his death. Brazilian publishing has also expanded in recent years, thanks in part to the explosion of small publishing houses. The picture that emerges is that of a great mosaic – albeit with gaps – which is interested in both the classics (for obvious reasons) and contemporary literature. In addition to the global phenomenon of Elena Ferrante, contemporary authors include Viola Ardone, Maria Grazia Calandrone, Donatella Di Pietrantonio, Antonio Scurati, Igiaba Scego, Roberto Calasso and Alessandro Piperno, Alessandro Baricco, Antonio Tabucchi, Michele Mari and so on, right through to poetry, with names like Pier Paolo Pasolini, Valerio Magrelli, Enrico Testa, Eugenio De Signoribus, Fabio Pusterla, Patrizia Cavalli and Patrizia Valduga. In this sense, the role of the only two Italian cultural institutes in Brazil (São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro) is fundamental in encouraging this circulation and, through collaboration with universities and other local bodies, in promoting and disseminating Italian books. Equally important is the role of translators, some of whom, through their efforts and temperament, are veritable mediators of Italian literature in Brazil.