The Italian book in Brazil

Part One

Author: Patricia Peterle, Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina

Thinking about the panorama of Italian literature translated in Brazil takes us back to many other contact points marking much of the cultural history of the country over the seas. Suffice it to recall the name of Amerigo Vespucci, in the famous expedition of 1499, who later landed in Bahia; the fortune of Metastasio and the intense relations easily identifiable in the archipelagoes of Minas Gerais as Sérgio Buarque de Holanda has pointed out; the waves of migration; the name of Empress Teresa Cristina of Bourbon, to whom Aniello Angelo Avella has dedicated important studies; not to mention all the architects, sculptors, painters, musicians, singers and writers who passed through Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo in particular.

However, a fact of fundamental importance to understand the formation of the publishing market in the then Portuguese colony is the arrival in 1808 of Dom João VI and his court in Rio de Janeiro. Indeed, until 1808 it was forbidden to print any kind of material in colonial Brazil. Such a scenario already indicates great limitations for publications written in Brazil and even more so for translation, in short for everything related to the circulation of books.

While in 1801 Rio de Janeiro only had two bookshops and no printing works, in 1890 there was already an enormous cultural growth as we can see from these numbers: 45 bookshops and 67 printing works. The start of what could only be called the publishing market, however, came with the relocation of the court due to the Napoleonic campaigns and, consequently, with the inauguration of the Imprensa Régia, the first printing house dedicated to printing books, newspapers and other documents. It is no coincidence then that most books initially arrived from Portugal or France, so much so that it can be said without a shadow of a doubt that Italian literature arrived through French channels. From the very beginning, the formation of the Brazilian cultural system was influenced closely by the French cultural environment.

With Brazilian independence in 1822, the period of formation of a national identity began and this also meant an expressed desire for independence from a cultural point of view. This feeling was reaffirmed and reasserted on the first centenary of independence, when the so-called Semana de Arte Moderna was organised in São Paulo in 1922. Mário de Andrade, Oswald de Andrade, and Tarsila do Amaral were some of the young writers and artists who brought forward ideas that might have seemed curious, outlandish and at the same time innovative. Authors who had undoubtedly read Dante, Marinetti, Palazzeschi, and had been influenced by the avant-garde, were defending creative freedom, as well as manifesting the need to rethink and restructure cultural relations and in the early 1920s. Indeed, Oswald and other Brazilian intellectuals made cannibalism a metaphor for talking about the relationship between cultures. The Brazilian 20th century thus opens with this urgency to devour and digest the art and the language of Europeans in order to find one’s own identity: the path of anthropophagy, in short.

Although the flow of translations increased considerably during the 20th century, the first translations can be traced back to the second half of the 19th century. Silvio Pellico’s My Prisons, published in 1832, is a book, for example, that a century later would be read and would become a central reference, along with Gramsci‘s Notebooks, for the Brazilian writer Graciliano Ramos in his Memórias do Cárcere (1953). Ramos, among others, was translated by Edoardo Bizzarri in Italy, the first director of the ‘Instituto Cultural Ítalo-Brasileiro’, who arrived in São Paulo in 1951. Bizzarri is one of those lives in transit between the two cultures that left such a mark on the 20th century, bringing to Italy other Brazilian authors of the calibre of João Guimarães Rosa and Cecília Meireles.

Among the earliest translations circulating in Brazil is a little gem, the Ramalhete poético do Parnaso Italiano, published in 1843. It was a wedding present for the Emperor Dom Pedro II and Teresa Cristina of Bourbon, edited and translated by Vincenzo De Simoni, an Italian physician rooted in Brazil since 1817, who is considered by critics to be the first translator of Dante into Portuguese, with some cantos included in this anthology. De Simoni was perhaps the first great figure of cultural mediation, precisely because in the Ramalhete poético he presents a certain canon of Italian poetry: Dante, Petrarch, Ariosto, Tasso, Metastasio, Alfieri and Monti, followed by other pieces that also offer a political vision mediated by selected texts by Pindemonte, Foscolo and Manzoni (an author who would later be translated by Dom Pedro II himself).

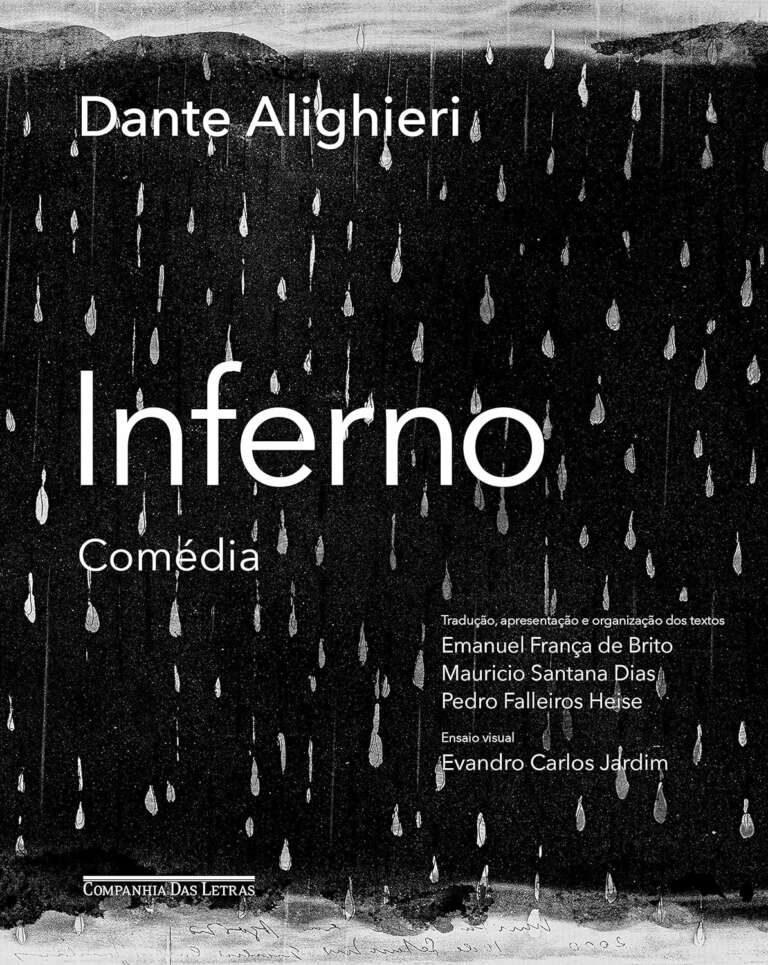

The figure of Dante, as is often the case in other latitudes, is nonetheless dominant. Indeed, the imagery of the Commedia exerted, and continues to exert, an attraction in some readers. Indeed, that ‘muse-worthy bond’, broken by the porous passage between languages, is perhaps precisely the quid that attracts and challenges the Commedia‘s translators. A score that must be continually remade because a new variation always demands new rewriting. We could mention a few who have accepted this challenge, starting with Gonçalves Dias, a writer of Brazilian romanticism, later translated by Ungaretti in Italy, who in 1844 proposed his version of part of Canto VI of Purgatory. The great Brazilian prose writer of the 19th century, Machado de Assis, then put his Portuguese to the test in 1874 in his translation of Canto XXV of Inferno. But mention must also be made of Henriqueta Lisboa, already in the 20th century, a poet who translated texts by Dante, Leopardi, Ungaretti and Pavese, but without publishing them in a volume. Or in the mid-1950s, the poet Dante Milano who published a translation of three cantos (V, XXV, XXXIII) of Inferno, or the brothers Augusto and Haroldo de Campos. The version made during the 1970s by Cristiano Martins, who devoted himself to the three cantiche, is still considered the most poetic, and precedes the work by Italo Eugenio Mauro twelve years later, who published his Commedia in 2007. More recently, three university professors, Maurício Santana Dias, Pedro Heise, and Emanuel Brito, have proposed a new translation project, and in 2021 a volume of Inferno was published.

These are just a few contact points of many in a long relationship between the two literary systems.

According to the Index Translationum – perhaps the data are not entirely up to date, but they nonetheless give us an idea–, the Brazilian market counts 50,229 published translations (not only literary ones), of which 2,011 from Italian, 5,764 from French and 3,161 from German. Most translations are obviously from English, 34,047.