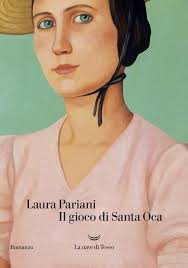

Il gioco di Santa Oca

A book I’d like to translate

Every month newitalianbooks asks a translator to suggest a book he or she would like to translate. This month, Katherine Gregor presents:

Laura Pariani, Il gioco di Santa Oca, Milan, La Nave di Teseo, 2019

Rights: Piergiorgio Nicolazzini Literary Agency, Milan

Il gioco di Santa Oca was shortlisted for the Premio Campiello in 2019. It’s a novel set in 17th century Lombardy, written in the style of an epic poem. It’s a tale of rebellion, freedom, and of brave women who defy the convention of their times.

In a land abused by the aristocracy and pillaged by foreign soldiers, a charismatic rebel with a secret, at the head of a band who take refuge on the moors, preaches the Gospel in a way no one has heard it before. Naturally, the State and the Inquisition resolve to capture him.

Two decades later, the storyteller Pùlvara walks across the same moors, where pagan beliefs sometimes run deeper than Church teachings, and trades tales for bed and board, recounting the feats of the legendary rebel. As the day when the wall between the world of the living and the world of the dead is thin draws nearer, Pùlvara approaches her true destination and, guided by a she-wolf, is finally able to find an old friend and set the spirit of a tormented body free.

Instead of holding a dystopian future up as a mirror to our society, Laura Pariani uses a historical past as the canvas on which every event she describes has happened and is happening in our own century.

Katherine Gregor

Below, we offer, with the permission of Piergiorgio Nicolazzini Literary Agency, a translation sample by Katherine Gregor of one page of Il gioco di Santa Oca

She pushes the leafless branches of a hawthorn aside and ventures through nettles, belly-high; her long skirt hinders her somewhat and to save it from getting muddy she pulls it up to her knees. She pricks up her ears and listens to the life of the moorland throbbing around her: trees falling, branches rotting on the ground amid soaked leaves; the mist bestows the same caress upon the leech and the fern, and makes no difference between the hornbeam and the briar. She sniffs the air, which smells of rotting timber, and peers beyond the English oaks. The sense that a hundred eyes are following her down this silent path sends a shudder through her: smelling her, the hare springs into a run; the fox crouches down in the heather; the boar stops schooling its offspring for a moment then, without rushing, disappears deep into the heart of the forest; the kite watches her while flying high above; the nightjar counts the sins Pùlvara carries on her back, then opens its beak as though about to snatch her soul.

Heedless of them, Pùlvara stubbornly keeps going. She once knew this familiar land’s end, she travelled down and across it many times twenty years ago, which is why she picks up on many details of the moorland with her heart and her memory.

She stretches her back, a heavy bag weighing down her shoulders. It’s a long way to the river, and the days are growing shorter, so she must make haste. That’s when she hears a mysterious, worrying sound in the distance. Is it a horn? It rises, like a lament, to the darkening sky.

Pùlvara’s hand rushes to the gypsy knife she wears at her belt; her fist also clenches around the knotty stick: she wasn’t born yesterday and, if need be, could defend herself.

[…]

The moorland seems to be holding its breath now, while the horn keeps calling. A sound in the thick of the trees. Pùlvara feels a pang of anxiety in her chest, the hated companion of a walk across a moorland which, from one moment to the next, can turn into a place of spells. She turns abruptly and briefly glimpses two dark faces and eyes glistening above shaggy beards. Truth or a trick of the imagination? Blink and they’ve gone, as the horn is sounded again. Two forest divinities and two sounds of the horn? Number four, tied to the moon cycle that rules over childhood. What does the number four remind you of, Pùlvara? Your infancy in Milan, the shrill voices of your four siblings squatting on the bank of the Naviglio, watching barges entering the city, the opportunity to savour the taste of a joyfully adventurous freedom at the horse market past Porta Ticinese or in Vico delle Oche outside San Vittùr, back in the days of once upon a time and there didn’t used to be, before the scourge of the plague wiped out your family … Number four, the year of the sun in the Game of the Goose, which is so much like life itself. Step forth, Pùlvara. Use your judgement and have faith: because as the ancients knew, the goose is the Lady of the Animals. So be guided by her.

After all, in the beginning there is always a feathered creature.

By Laura Pariani

Translated by Katherine Gregor